HIV breakthrough: New treatment shows extraordinary trial results leading to hopes for more efficient vaccines

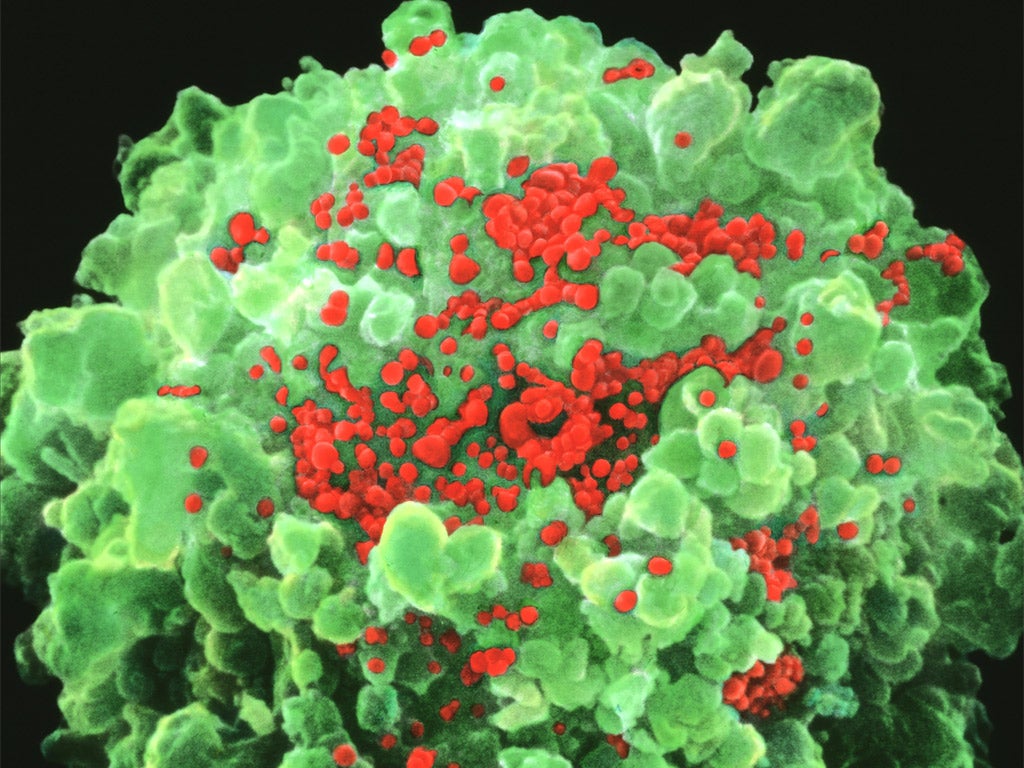

The transfusion of a synthetic antibody specifically designed to block the key viral protein receptor needed to infect human blood cells resulted in a dramatic lowering of the virus

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A new type of HIV treatment involving the transfusion of a synthetic antibody designed to prevent the virus from attacking human cells has shown startling trial results.

Patients injected with the antibody saw a 300-fold reduction in their viral “load” – the amount of HIV circulating in their blood. The antibody has been specifically designed to block the key viral protein receptor needed to infect human blood cells.

Previous tests on HIV antibodies had produced disappointing results. But the latest clinical trial resulted in a dramatic lowering of the virus, which was maintained for several weeks after the initial injection for some patients.

The researchers believe that using synthetic antibodies designed to become attached to the surface proteins on the outer membrane of HIV could provide an alternative form of treatment to anti-retroviral drugs, and may also help to design therapeutic vaccines.

It is the first time that a new generation of HIV antibodies has been tested in phase 1 clinical trials. Further trials could eventually lead to them being used in combination with existing anti-retroviral drugs to maintain better control over the infection to prevent the onset of Aids, the scientists said.

“One antibody alone, like one drug alone, will not be sufficient to suppress viral load for a long time because resistance will arise,” said Marina Caskey of the Rockefeller University in New York, the lead author of the study published in the journal Nature.

“What’s special about these antibodies is that they have activity against over 80 per cent of HIV strains and they are extremely potent,” Dr Caskey said.

HIV-infected patients in the trial received different doses of the antibody. The eight patients who received the highest dose showed up to 300-fold decreases in the amount of circulating HIV in their blood, and in half of them the viral load remained below starting levels at the end of the eight-week study.

“This exciting novel study shows for the first time that antibodies may have a place in the line of therapies directed against HIV,” said Professor Vincent Piguet, director of the institute of infection and immunity at Cardiff University, who was not involved in the study.

“This is good news for the fight against HIV, but a fully developed antibody to treat HIV-1 might still take a few years to develop,” he added.

The antibody is known as 3BNC117 and was originally isolated in the same laboratory where the latest work was carried out.

The antibody is a protein that attaches to the key receptor on the outer protein coat of the HIV virus which binds to the membrane of the human T-cells it infects.

Tests have shown that 3BNC117 is effective at controlling 195 of the 237 strains of HIV – making it a “broadly neutralising” antibody that could be used in many HIV patients, the scientists said.

These broadly neutralising antibodies are naturally produced in about 10 or 30 per cent of people with HIV, but only after several years of infection when the virus has typically evolved to “escape” from these powerful antibodies.

By making synthetic copies of the antibody and infusing large enough amounts of them at an earlier stage in a patient’s infection, the researchers hope to suppress the infection and make it easier to control with the help of other treatments such as anti-retroviral drugs.

“In contrast to conventional anti-retroviral therapy, antibody-mediated therapy can also engage the patient’s immune cells, which can help to better neutralise the virus,” said Dr Florian Klein of Rockefeller University and a co-author of the study.

Dr Andrew Freedman of Cardiff University, said: “Although such antibody treatment would not be sufficient on its own, it might prove useful in combination with drug therapy, as a means of achieving better long-term control or even cure of HIV infection. It may also be effective as a way of preventing HIV infection, in the absence of a vaccine.”

HIV treatments: Breakthroughs and false dawns

A trial earlier this year involving 12 NHS trusts across England found that gay men who took a daily pill containing a cocktail of two anti-retroviral drugs significantly reduced their risk of contracting HIV by an unprecedented 86 per cent. The Proud study found that pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) could be a “game changer” in reducing new infections and may be cost effective in terms of reducing the rise of HIV disease.

Two other patients with HIV who had been thought to be cured following treatment for blood cancer suffered a viral “rebound” in 2013. Researchers in Boston said they had been unable to detect any signs of HIV in either patient following their treatment – a bone-marrow transplant for lymphoma cancer. However, both patients have since returned to taking anti-retroviral drugs after HIV reappeared in their bloodstream.

Timothy Brown, the “Berlin patient”, remains the only person with HIV to be “functionally cured”. Mr Brown, who now lives in San Francisco, received a bone-marrow transplant in 2007 to treat leukaemia. The donor was carrying a specific mutation that prevents HIV from attacking white blood cells. However, such transplants are risky, expensive and not suitable for widespread treatment.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments