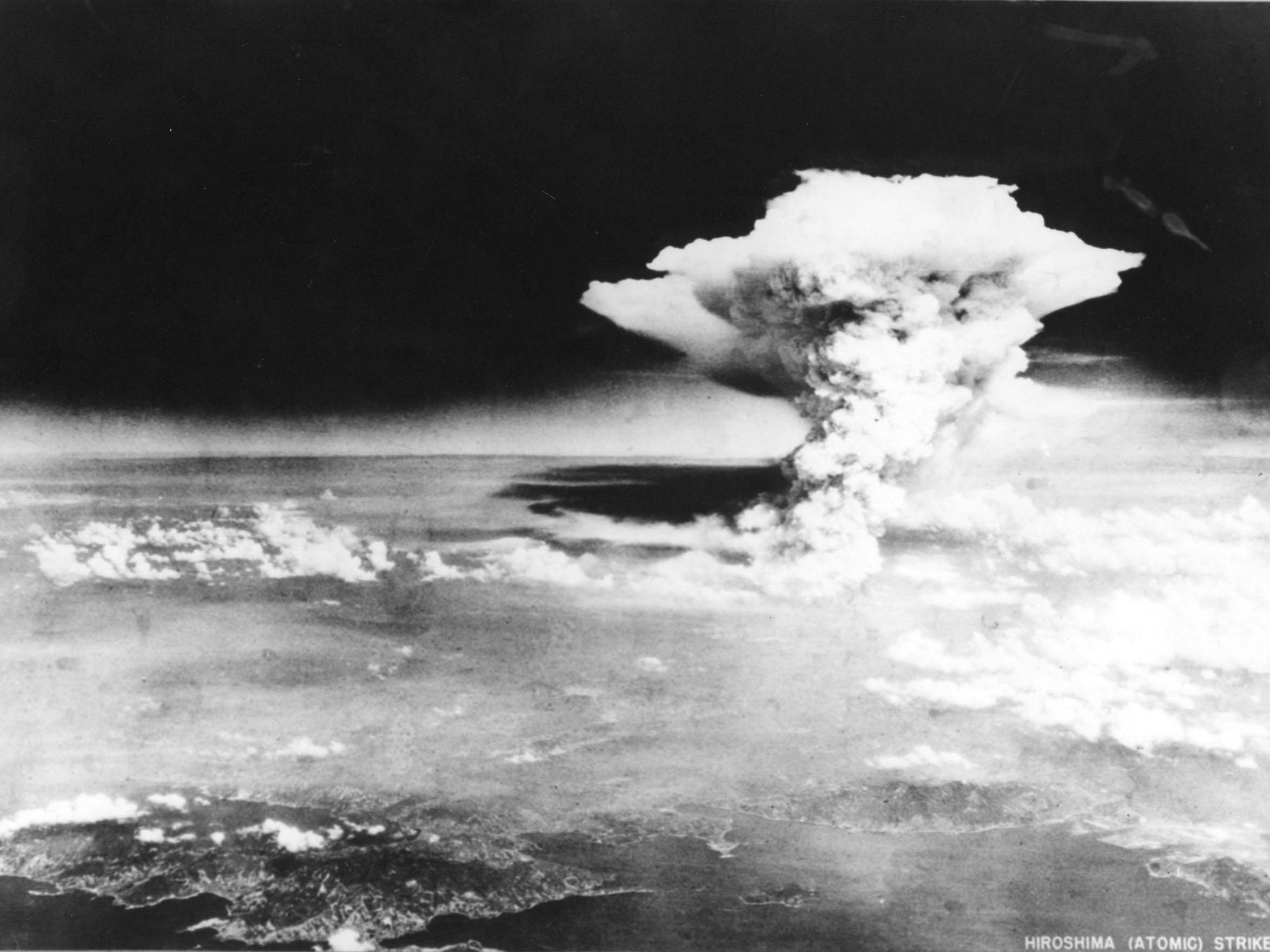

Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Study shows what would happen in London under a modern nuclear attack

Entire city would be wiped out in seconds, experts say

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This week marks 75 years since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan by the US military in August 1945.

An estimated 90,000 to 140,000 people in Hiroshima (up to 39 per cent of the population) and 60,000 to 80,000 people in Nagasaki (up to 32 per cent of the population) were killed by the two nuclear bombs.

To date, the bombs, nicknamed Little Boy and Fat Man, are the only two nuclear weapons deployed in war, and are considered small in comparison to the warheads in nuclear arsenals today.

Their use ushered in a new nuclear age in which superpowers have amassed huge quantities of powerful nuclear weapons.

Londoners would only have “a matter of minutes” before being warned of an impending nuclear attack, experts have said, with one bomb in today's arsenal enough to wipe out the entire city.

If an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) were to head to London, the warning time would be measured in minutes, not hours, Dr Lyndon Burford, a post-doctoral research associate in the Centre for Science and Security Studies at King's College London, told PA.

“The Prime Minister would have minutes to make it to a safety bunker,” he said.

When Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, temperatures near the site of the explosion were estimated to be 300,000C (540,000F) - around 300 times hotter than the furnaces used for cremation, so humans nearby were almost instantly vaporised - reduced to their most basic minerals.

But the force of the blast and collapsing buildings was what killed most people. However, survivors from the blast and heat were then exposed to huge amounts of radiation, which ultimately killed thousands more.

According to an Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission report, 6,882 people examined in Hiroshima, and 6,621 people examined in Nagasaki, who were largely within 2,000 metres from the centre of the blast zone and who suffered injuries from the blast and heat, died from complications frequently compounded by acute radiation syndrome (ARS), all within about 20 to 30 days.

In Hiroshima, the thermal heat from the bomb sparked numerous fires, resulting in a firestorm in the city, cremating victims from the blast, killing more people and razing buildings - many of which were made from wood. A firestorm is a phenomenon in which a fire burns with such intensity, storm force winds rush to feed the fire from every point of the compass.

In the case of a modern nuclear attack on London, the damage would be far greater than in either Hiroshima or Nagasaki.

The nuclear weapons that exist in today’s arsenal are “much more powerful” than the ones used in 1945, said Matt Korda, a research associate for the nuclear information project at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS).

The warheads that bombed the Japanese cities on August 6 and 9 in 1945 achieved blasts of around 15-20 kilotons.

“By contrast, today's weapons can achieve yields of several hundred, sometimes over 1,000, kilotons, due to the introduction of multi-stage thermonuclear weapon designs during the early years of the Cold War,” Dr Korda said.

“A nuclear detonation of several hundred kilotons over the centre of London would destroy most of the city, and could break windows as far away as Croydon and Walthamstow (just under 10 miles away).”

Dr Burford said he is sceptical of the UK government's assertion that it could respond to a single nuclear use in an urban area to help victims of such an attack, citing a warning given by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in 2013 that, as things stand, “there is no effective way of delivering humanitarian assistance to victims of a nuclear blast”.

Dr Burford said: “We have learnt that ionising radiation has a gendered impact - women and girls are disproportionately impacted by the negative effects. We don't know why, but that's what the science says.”

The FAS estimates that around 91 per cent of all nuclear warheads are owned by Russia and the United States, with each having around 4,000 warheads in their military stockpiles.

The military theory of mutually assured destruction (MAD), in which a nuclear attack by one superpower would be met with an overwhelming nuclear counter-attack, thus acting as a deterrent to nuclear warfare, is a hotly debated topic.

Dr Burford said: “Many former military and governmental experts are increasingly pointing out that, even if deterrence did work in some instances - and we can never ‘know’ in the scientific sense, because deterrence is an internal, psychological process - in other cases, it is clear that luck played a significant role in preventing the use of nuclear weapons.

“So, did MAD work? Only if we accept that at a minimum, sometimes we just have to leave it to luck to determine whether or not we have a nuclear war.”

Professor Malcolm Chalmers, deputy director-general at the Royal United Services Institute, told PA the use of nuclear weapons against the UK is most likely to take place during a time of extreme national crisis or war.

“A deliberate 'bolt from the blue' attack cannot be ruled out altogether, but it is extremely hard to see what an enemy could hope to achieve,” he said.

Additional reporting by PA.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments