Underwater cables linked to deformities and poor swimming ability in lobsters

Experts say power cables should be buried beneath the seabed to help shield marine species.

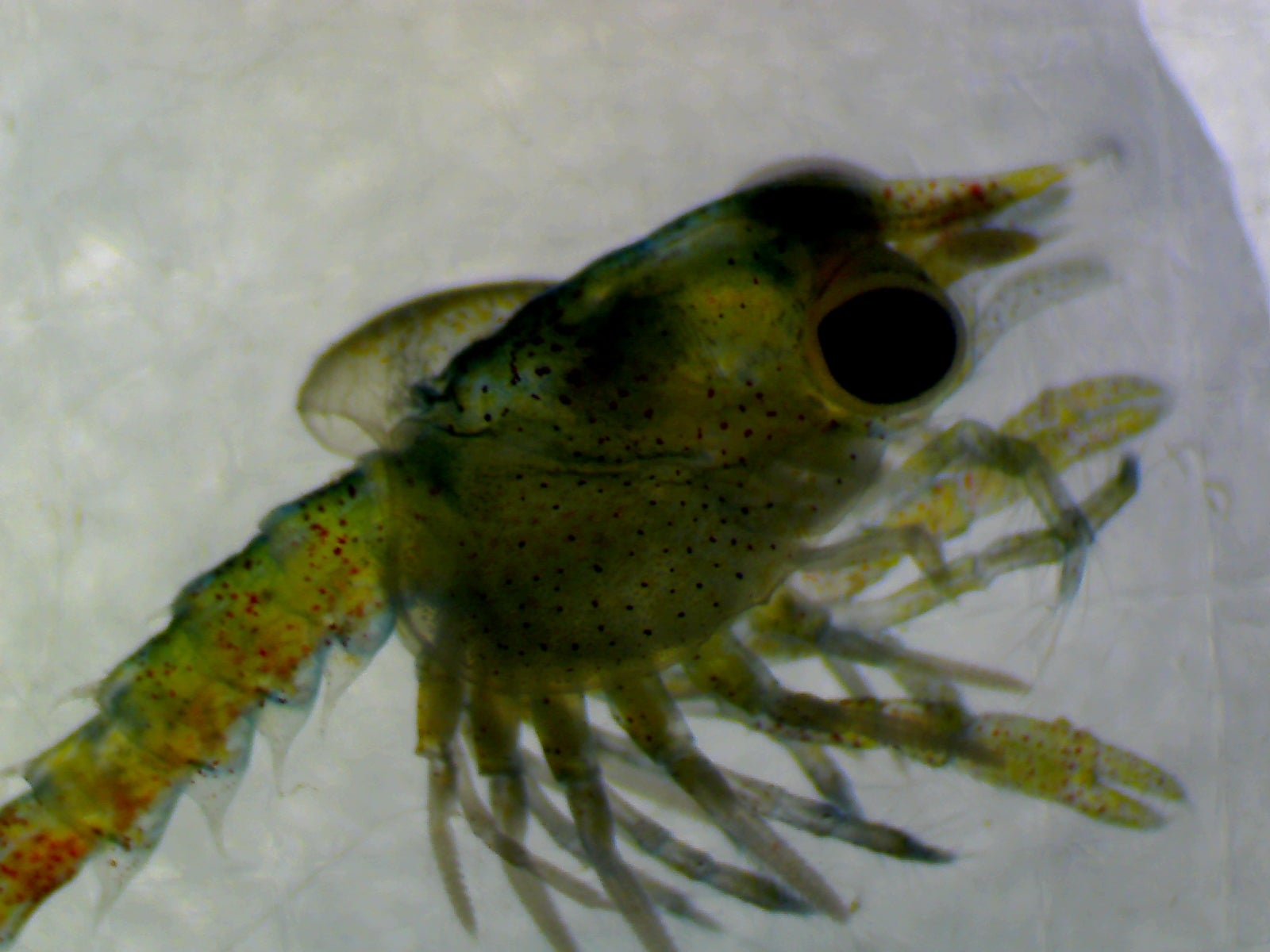

Lobster larvae exposed to the electromagnetic field of subsea power cables as eggs are more likely to develop deformities and cannot swim as well, new research suggests.

Marine scientists used a specialist aquarium laboratory at St Abbs Marine Station in the Borders to expose more than 4,000 lobster and crab eggs to a level of electromagnetic field predicted to be equivalent to that experienced near underwater cables.

Comparative groups of lobster and crab were not exposed in the research, which involved scientists from Heriot-Watt University in Edinburgh and St Abbs Marine Station.

Researchers found lobsters exposed to the field were three times more likely to be deformed than those which were not, with bent and reduced tail sections the most common deformities, while some had disrupted eye development or puffy and swollen bodies.

They were also three times more likely to fail a vertical swimming test to get to the surface to find food.

In contrast, electromagnetic field exposure did not appear to have much impact on crab larval deformities and swimming test success, though they were smaller than those not exposed.

With the expansion of marine renewable energy, the number of subsea power cables is rapidly increasing and researchers said consideration should be given to burying them under the seabed to help shield marine species.

Dr Alastair Lyndon, a marine biologist at Heriot-Watt University, said: “Lobsters were more affected than crabs by the electromagnetic field, at least in the short term.

“Both crab and lobster larvae exposed to the electromagnetic field were smaller, which could have an impact on their survival. Underwater, bigger means better able to avoid predators.

“The electromagnetic field had a much bigger impact on the lobsters.

“We put them through a vertical swimming test to check they could get to the surface to find food. The exposed lobsters were almost three times more likely to fail the test, by not reaching the top of the chamber, than the unexposed ones.

“Lobster isn’t an endangered species but it is under sustained pressure because of its commercial value.

“We should be aware of the need to shield them from electromagnetic fields, particularly during early development, as well as monitoring their long-term behaviour and development, which also goes for crabs.

“One potential solution is to bury the cables in the seafloor. This is already done for many marine renewable developments but can be expensive and difficult to maintain. It will be important to ensure its continued inclusion in the consenting process for future projects.

“We must decarbonise our energy supply, but we must also ensure there are as few unintended consequences as possible.”

The scientists said the findings about crabs were “reassuring”, but longer-term research is needed.

Petra Harsanyi, from St Abbs Marine Station, said: “Exposure to the electromagnetic field made the crab larvae smaller. While that hasn’t had an immediate effect, it does show that there’s an interference with their development.

“It would be interesting to monitor this over time to see whether these crabs have long-term impairments or increased mortality.”

The report was published in the Journal of Marine Science and Engineering.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks