World’s largest bacterium found which is size of human eyelash

The bacterum is the equivalent of a human the size of Mount Everest

Scientists have discovered the world’s largest bacterium in a Caribbean mangrove swamp.

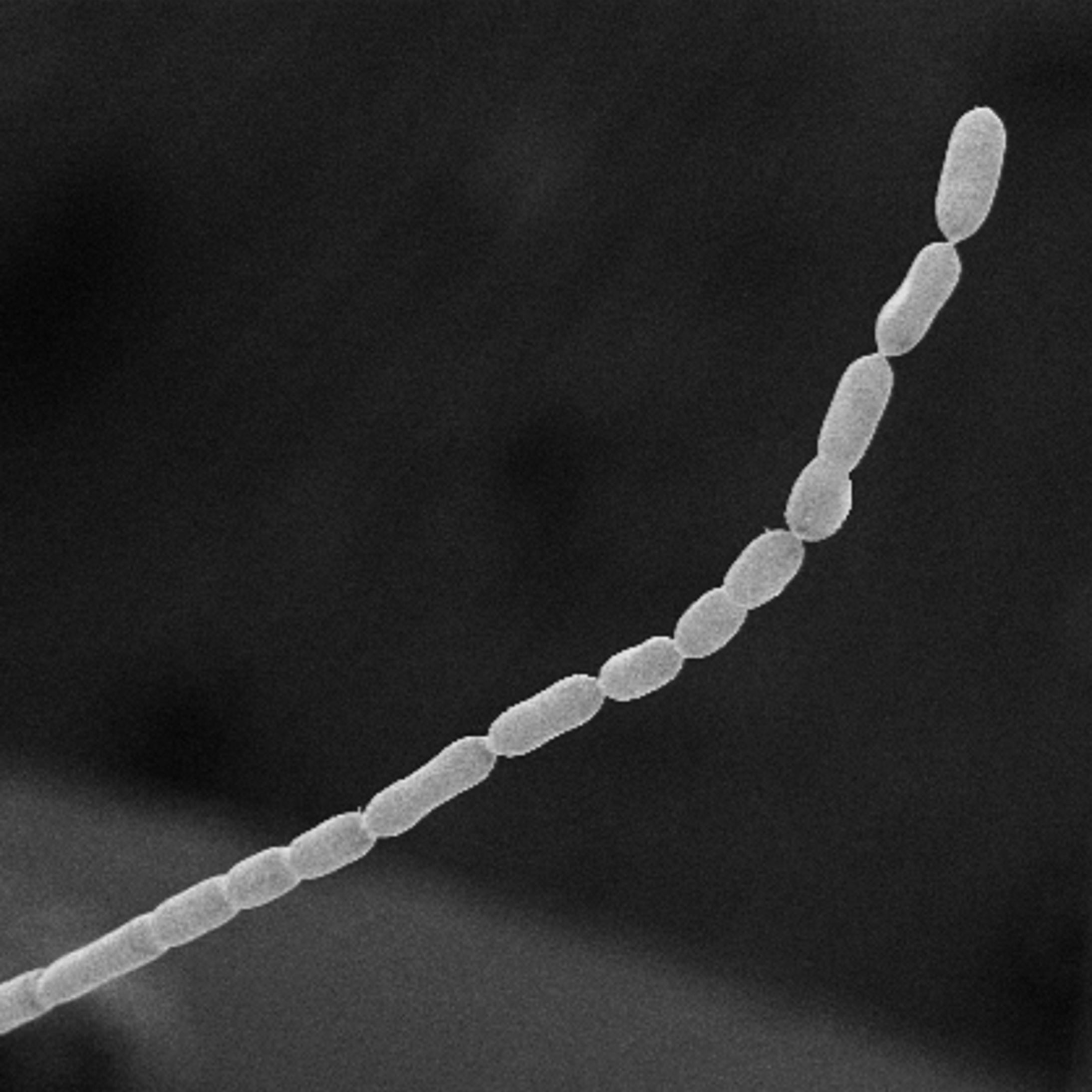

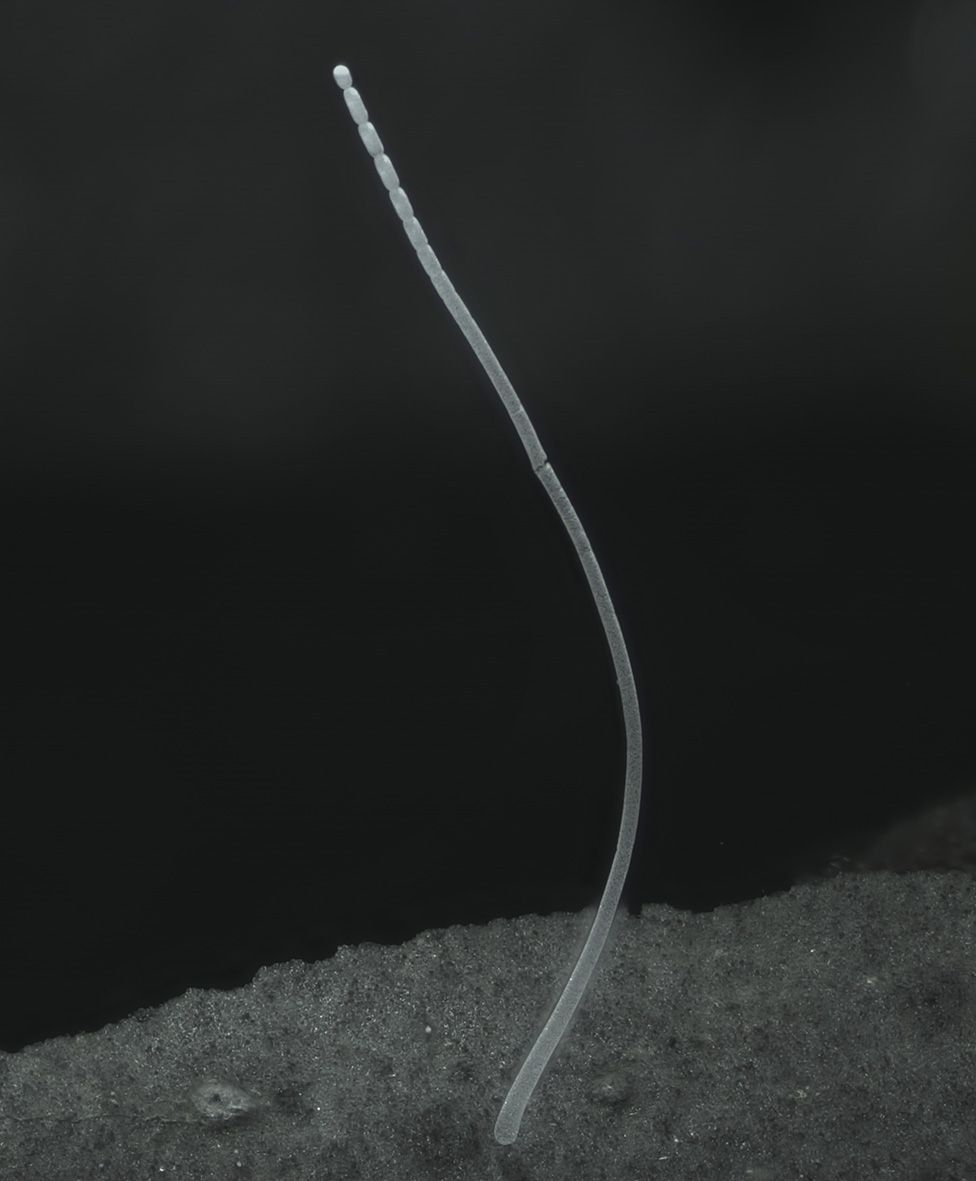

Although most bacteria are microscopic, Thiomargarita magnifica is the size of a human eyelash and can be seen with the naked eye.

The organism is not in fact dangerous to humans but has left scientists marvelling at its size.

"These bacteria are about 5,000 times larger than most bacteria. And to put things into perspective, it is the equivalent for us humans to encounter another human who would be as tall as Mount Everest," said Jean-Marie Volland from the Joint Genome Institute at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in the United States.

Measuring one centimetre long, the bacterium was discovered living on decaying mangrove tree leaves in the Caribbean.

The species belongs to the genus Thiomargarita. Professor Silvina Gonzalez-Rizzo, of the University of Antilles, Guadeloupe, explained how it was named: "Magnifica because magnus in Latin means big and I think it’s gorgeous like the French word magnifique.

She added: "This kind of discovery opens new questions about bacterial morphotypes that have never been studied before."

Her colleague Professor Olivier Gros came across the species in 2009 during an expedition to the mangrove swamps of Guadeloupe.

He said: "When I saw them, I thought, ‘Strange.’ In the beginning I thought it was just something curious, some white filaments that needed to be attached to something in the sediment like a leaf."

It was initially put to one side, but several years of scans and use of a gene sequencing technique later, scientists finally identified and classified the prokaryote.

Professor Silvina Gonzalez-Rizzo, who carried out the gene sequencing, said: "I thought they were eukaryotes - organisms with a nucleus. I didn’t think they were bacteria because they were so big with seemingly a lot of filaments.

"We realised they were unique because it looked like a single cell. The fact they were a ‘macro’ microbe was fascinating."

State-of-the-art scanners meant that the huge cells could be seen in three dimensions at high magnification and in exquisite detail.

The images confirmed that they were single cells rather than multicellular filaments.

Novel, membrane-bound compartments were also identified. These contained complex and plentiful clusters of DNA - called ‘pepins’ after the small seeds in fruits.

Dr Volland said: "The bacteria contain three times more genes than most bacteria and hundreds of thousands of genome copies that are spread throughout the entire cell."

Scientists established that T. magnifica is a chemosynthetic bacterium.

It makes its own fuel - sugar -by oxidising the sulphur compounds created by the decomposing organic matter that can be found in the mangrove swamp.

All it needs to grow, is to find something solid to cling on to.

"I found them attached to oyster shells, to leaves and branches, but also on glass bottles, plastic bottles, or ropes," said Prof Olivier Gros, a microbiologist with the University of the Antilles.

"They just need some hard substrate to be in contact with the sulphides and in contact with the seawater to get oxygen and CO2. The highest concentration of ThiomargaritaI found was on a plastic bag - unfortunately."

A full description of the bacterium has been published in Science Magazine.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks