Galactic wind that controls star birth detected in depths of universe

Flows of gas in galaxy 12 billion light years from Earth provide unprecedented insight into formation of stars during early days of universe

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Powerful winds from the dawn of the universe have been detected by scientists for the first time - 12 billion light years away from Earth.

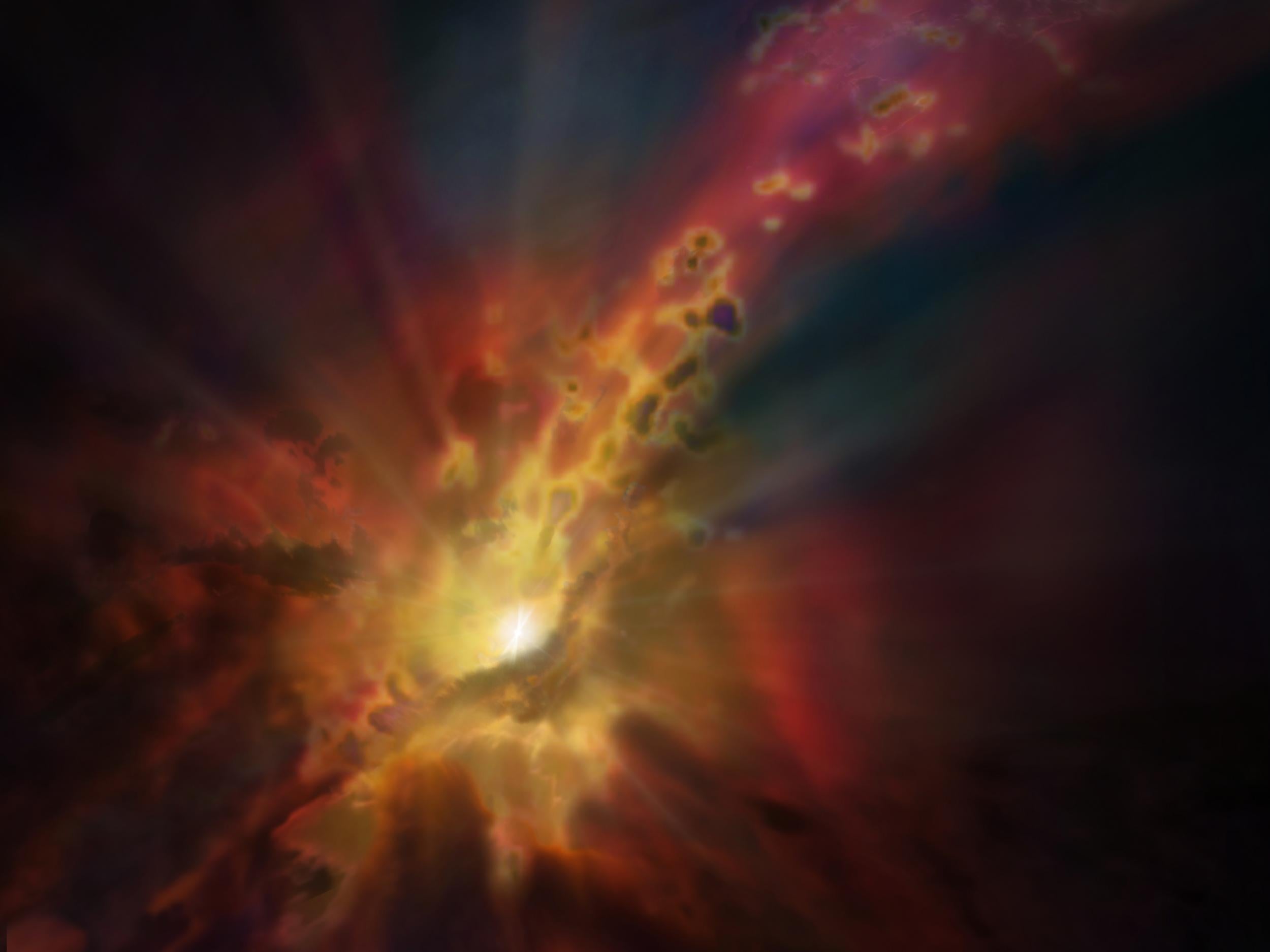

Travelling at 500 miles per second, astronomers think these gusts of cosmic gas are instrumental in controlling the emergence of stars and the galaxies they are part of.

“Galaxies are complicated, messy beasts, and we think outflows and winds are critical pieces to how they form and evolve, regulating their ability to grow,” explained University of Texas at Austin astronomer Dr Justin Spilker, who led the research.

Using observations from the ALMA observatory in northern Chile, Dr Spilker and his colleagues were able to detect traces of these winds from a time shortly after the Big Bang, when the universe was only one billion years old.

Galaxies such as our own, the Milky Way, have a history of relatively slow, controlled star birth, with about one new star emerging every year.

However, thousands of stars can emerge in the same space of time in starburst galaxies.

These will rapidly consume the gas reservoir they rely on to form new stars, so their lifespans tend to be relatively short.

Galaxies avoid this early death when they eject vast quantities of gas early on, slowing down the rate of star formation and producing galactic winds.

These astronomical weather patterns can be seen in nearby galaxies using conventional X-ray and radio techniques from Earth.

However, identifying them in the farthest reaches of the universe, which provides insight into its early years, is far harder.

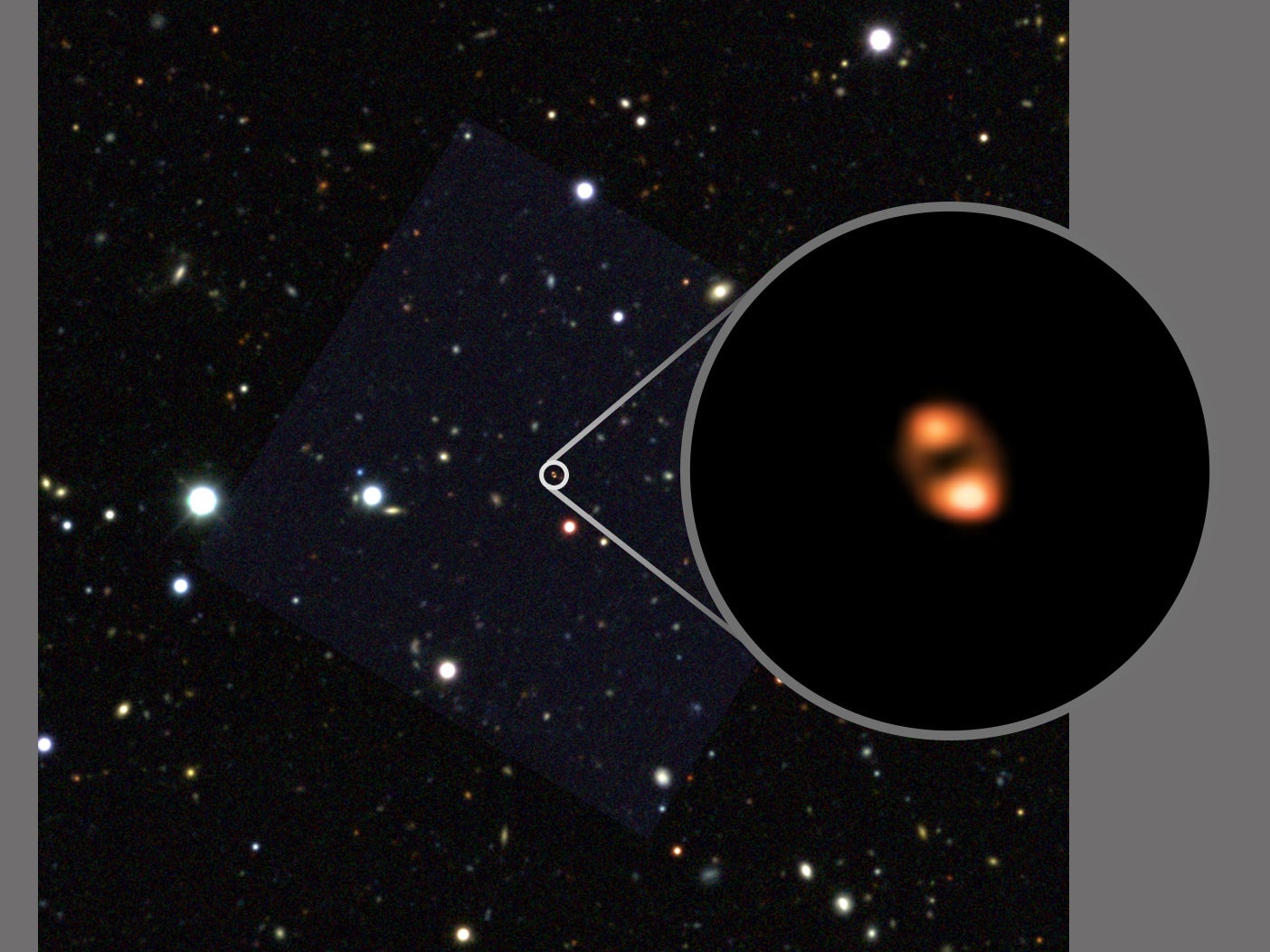

ALMA was able to pin down the effect in the galaxy known as SPT2319-55 using gravitational lensing, the process by which gravity bends light and in doing so magnifies events that would otherwise be impossible to observe using existing technology.

This technique has previously allowed scientists to identify planets far beyond the Milky Way for the first time.

In their distant galaxy, the team was able to detect large amounts of cold gas flowing outwards from the ancient galaxy at approximately the same rate as new stars are forming.

“So far, we have only observed one galaxy at such a remarkable cosmic distance, but we’d like to know if winds like these are also present in other galaxies to see just how common they are,” said Dr Spilker.

“If they occur in basically every galaxy, we know that molecular winds are both ubiquitous and also a really common way for galaxies to self-regulate their growth.”

As gas is ejected away from the galaxies themselves, it will either drift out into the wider universe or gradually rain back down into the galaxy and form stars in a feedback loop.

The winds likely form either as supernovas within the galaxies explode or due to the effects of supermassive black holes releasing bursts of energy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments