Fountain of youth? Scientists discover why wounds heal quicker for young people

Hopes rise for new drugs and treatments to speed healing process for the elderly

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The mystery of why wounds heal more quickly in the young compared to the elderly may soon be solved following the discovery of two of the genes involved in tissue regeneration.

Scientists believe that the findings will help to develop new drugs and treatments for faster wound-healing as well as shedding light on the ageing process itself, and what could amount to a genetic "fountain of youth".

Two teams of researchers found separate genes that accelerate tissue regeneration in laboratory mice. Both genes, which are also present in the human genome, are more active in young mice compared to older mice.

The scientists believe that the genes, called Lin28a and IMP1, are designed to be especially active during the foetal stages of development and are gradually turned off as an animal ages - which could explain why wounds take longer to heal in the elderly and how ageing occurs.

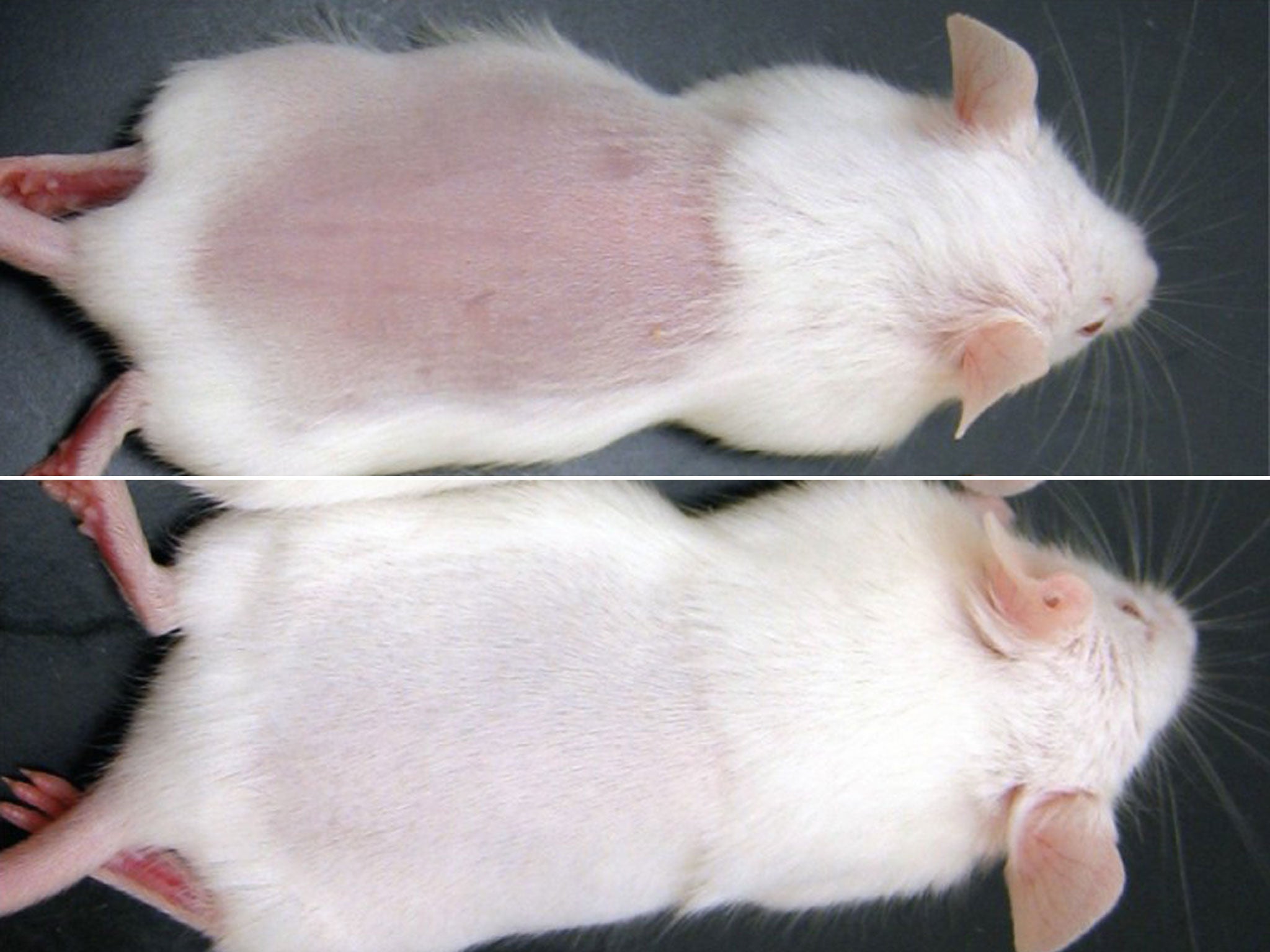

One of the teams, led by George Daley of the Boston Children's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, activated the Lin28a gene in adult mice and found that shaved fur on their backs grew back much faster than in ordinary adult mice where the gene had not be artificially boosted.

"It sounds like science fiction, but Lin28a could be part of a healing cocktail that gives adults the superior tissue repair seen in juvenile animals," said Dr Daley, whose study is published in the journal Cell.

Asked what the implications are for human health, Dr Daley said: "My strongest conclusion is that Lin28a, or drug manipulations that mimic the metabolic effects of Lin28a, enhances wound healing and tissue repair, and thus in the future might translate into improved healing of wounds after surgery or trauma in patients."

The study revealed that the Lin28a gene is responsible for a protein that binds to the key molecules of RNA involved in the metabolism of energy within the mitochondria, the "power packs" of the cells. The result is that when the gene is active, the cells are better and more efficient at repairing themselves - the activated genes also accelerated the repair of injuries.

Tissue regeneration is important in early foetal development and when damaged tissues need to be healed. A gradual loss of tissue regeneration and repair is one of the hallmarks of ageing so anything that could improve it could lead to anti-ageing treatments

"We were surprised that what was previously believed to be a mundane cellular 'housekeeping' function would be so important for tissue repair," said Shyh-Chang Ng of Harvard Medical School, the lead author of the Cell study.

"One of our experiments showed that bypassing Lin28a and directly activating mitochondrial metabolism with a small-molecule compound also had the effect of enhancing wound healing, suggesting that it could be possible to use drugs to promote tissue repair in humans."

The second gene, IMP1, also produces a protein that binds to the RNA molecules, but this time it promotes the self-renewal of key stem cells during foetal development, and also during tissue repair in later life, said Hao Zhu of the University of Texas in Dallas.

"This finding opens up an exciting possibility that metabolism could be modulated to improve tissue repair, whereby metabolic drugs could be employed to promote regeneration," Dr Zhu said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments