Are falling sperm counts really an ‘existential threat’ for humanity?

Among fears that an observed fall in sperm count may threaten the future of the human race, Rachel E Gross writes that all may not be quite as simple as it seems

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Male scientists have long waxed poetic on the contents of their testes. “Sperm is a drop of brain,” wrote the ancient Greek writer Diogenes Laertius. Leonardo da Vinci drew the penis with a sperm duct that connected directly to the spinal cord. The 17th-century microscopist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek claimed that each sperm cell contained within it a folded-up human being waiting patiently to unfurl.

For nearly as long, scientists have fretted about sperm’s seemingly inevitable decline. Most recently, a series of alarming headlines – as well as a new book by an public health researcher at Mount Sinai Medical Centre in New York – warned that falling sperm counts might threaten the future of the human race. “It’s a global existential crisis,” says Shanna H Swan, author of the book Count Down.

Most of these headlines can be traced to an influential 2017 meta-analysis by Swan and others, which found that sperm counts in Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand had plummeted by nearly 60 per cent since 1973. The authors screened 7,500 sperm-count studies from around the world, weeded out most of them and ultimately analysed 185 studies on 43,000 men worldwide.

They called the decline a “canary in the coal mine” for waning male reproductive health worldwide. Today, the authors would revise that statement. “There is clear and present alarm now,” says Dr. Hagai Levine, a public health researcher at Hebrew University-Hadassah Braun School of Public Health and a co-author on the 2017 review. “The canary is in trouble now.” Swan agrees.

Now a group of interdisciplinary researchers from Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology contend that fears of an impending Spermageddon have been vastly overstated. In a study published in May in the journal Human Fertility, they re-evaluated the 2017 review and found that it relied on flawed assumptions and failed to consider alternate explanations for the apparent decline of sperm.

Sperm count has other limitations as a metric. It takes around two months for stem cells in the testes to develop into new sperm, meaning that any single count is merely a snapshot of an evolving landscape

Sarah Richardson, a Harvard scholar on gender and science and the senior author on the new study, calls the conclusion of the 2017 review “an astonishing and terrifying claim that, were it to be true, would justify the apocalyptic tenor of some of the writing”. Fortunately, she and her co-authors argue, there is little evidence that this is the case.

The 2017 authors were “methodologically rigorous” in screening sperm-count studies for quality and consistency, Richardson and her colleagues write. However, even the data that passed muster was geographically sparse and uneven and often lacked basic criteria like the age of the men. Moreover, its authors took for granted that a single metric – sperm count – was an accurate predictor of male fertility and overall health.

No one knows what an “optimal” sperm count is. The World Health Organisation sets a range of “normal” sperm count as from 15 to 250 million sperm per millilitre. (Men produce about 2 to 5 millilitres per ejaculation.) But it isn’t clear that more is better. Above a certain threshold – 40 million per millilitre, according to the WHO – a higher count does not mean a man is more fertile.

“Doubling your sperm count from 25 to 50 million doesn’t double your chances,” says Allan Pacey, an andrologist at the University of Sheffield and the editor of Human Fertility. “Doubling it from 100 to 200 million doesn’t double your chances – in fact it flattens off, if anything.”

Germaine M Buck Louis, a reproductive public health researcher at George Mason University, agrees that sperm count is a poor indicator of fertility. “We don’t see it predicting much of anything, especially in the context of a partner with a healthy female pelvis,” says Buck Louis, who was not involved in the sperm-count studies.

The authors of the 2017 study inferred that lower sperm counts equated to lower fertility – even though the sperm-count declines they documented all took place within the “normal” range, Richardson notes. “It’s similar to the whole conversation around testosterone – more is better, and more is manlier,” she says. “That’s really a point we make, that there is no known normal or baseline for average population sperm counts.”

Sperm count has other limitations as a metric. It takes around two months for stem cells in the testes to develop into new sperm, meaning that any single count is merely a snapshot of an evolving landscape.

“Something that’s going on in a man’s body one month may be totally different from what’s happening the next month, and the effects on sperm count might be changing also,” says Meredith Reiches, an author on the 2021 paper and a biological anthropologist at the University of Massachusetts, Boston.

It also overlooks a vital piece of the infertility puzzle: women. Focusing only on the male metric leaves out key interactions between sperm, the female reproductive tract and the egg. “It’s very important, actually, to look at the couple,” says Dr Bradley D Anawalt, a reproductive endocrinologist at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

In her book, Swan suggests that sperm counts have plummeted largely because of the rise of endocrine disrupters, a class of hormone-mimicking chemicals found in everything from shampoo to TV-dinner packaging. (She also cites lifestyle factors like obesity, alcohol, and smoking).

Richardson and her co-authors suggest an alternative: Perhaps sperm levels naturally rise and fall over time and within populations. The question has not been explored by reproductive researchers and cannot be answered easily, as global sperm counts before 1970 are largely unknown.

Male infertility contributes to at least half of all cases of infertility worldwide. Yet historically, women have shouldered most of the blame for the inability to conceive

There are other possible explanations, as well. Sperm-counting is a tricky business and notoriously prone to human error, Pacey says. (“I say it from the point of view of someone who spent 30 years counting sperm and knows how difficult it is,” he adds). In a 2013 review article, he noted that as methodologies for counting had improved and been standardised since the 1980s, sperm counts had appeared to fall. In other words, it may simply be that earlier scientists were over-counting sperm.

Swan and Levine agree that exploring these alternative hypotheses was important, so that threats to reproductive health could be prevented. “We showed evidence for decline, and raised alarm,” Levine writes in an email. “We need to study the causes, including the unlikely possibility of non-pathological decline.”

There was one point that every author agreed on: Men’s reproductive health matters. And until now, it has been surprisingly neglected.

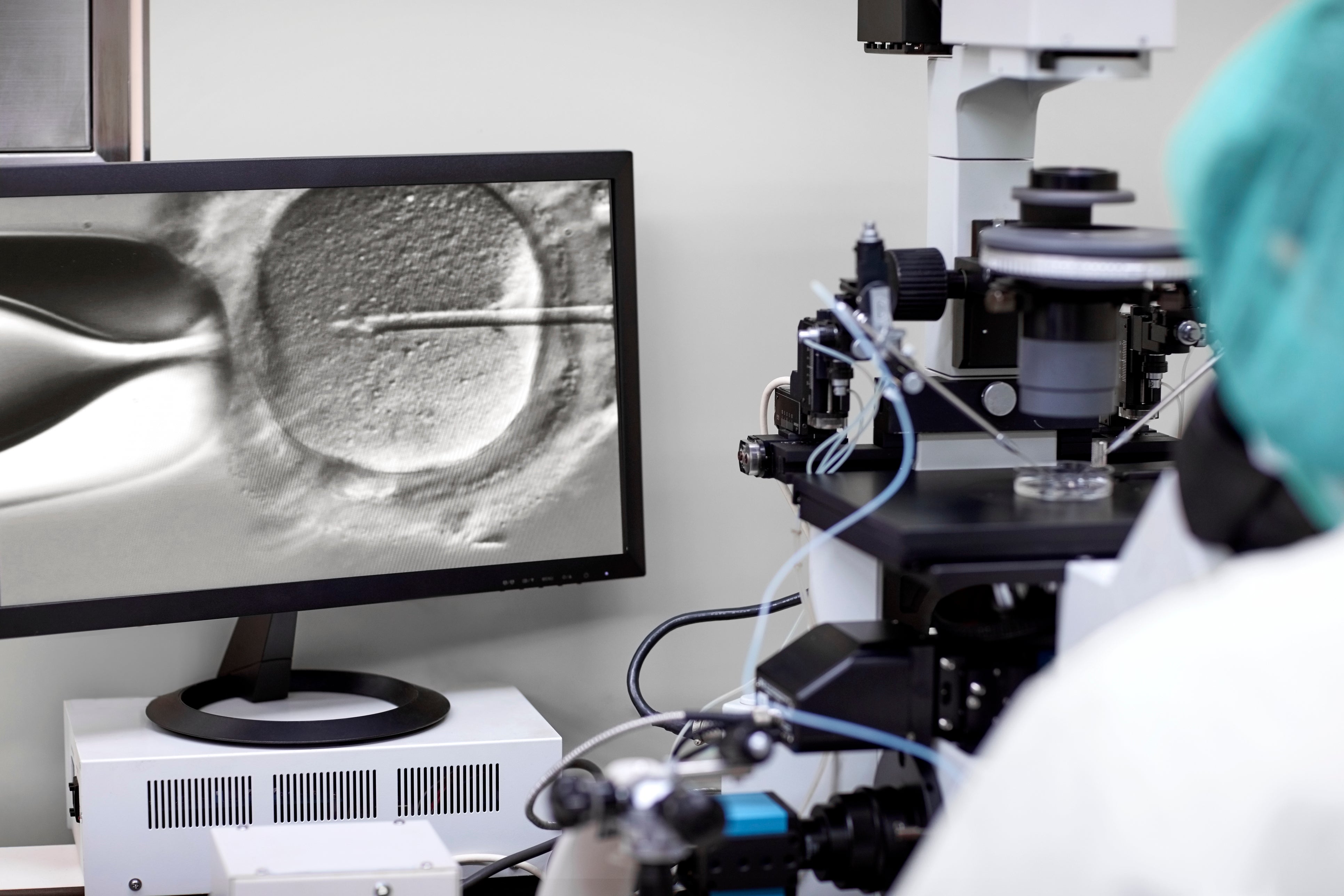

Male infertility contributes to at least half of all cases of infertility worldwide. Yet historically, women have shouldered most of the blame for the inability to conceive. And with the rise of reproductive technologies like in vitro fertilisation, women’s bodies are the ones that have been meticulously measured and tracked by reproductive medicine.

As a result, science still lacks basic knowledge when it comes to sperm, says Rene Almeling, a sociologist of medicine and author of GUYnecology: The Missing Science of Men’s Reproductive Health.

“We have built up such a medical infrastructure around the fertility and reproductivity of women’s bodies that we haven’t asked some of the basic questions about men’s reproductive health, ”Almeling says. “There is just so, so much basic research still to be done about sperm.”

The main qualities of sperm that infertility specialists look at nowadays – how many, what shape and how they swim – have not changed in the past 40 years, says Dr Abraham Morgentaler, a urologist and founder of Men’s Health Boston.

Morgentaler, who worked at a semen analysis lab at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre in the 1980s, attributes this stagnation to the rise of IVF and other technologies, which have become front line treatments for almost any male factor fertility problem. “It almost doesn’t even matter what’s wrong with the sperm,” he says.

These knowledge gaps radiate out to all bodies. Swan says part of her motivation for writing the book was that she wanted to see men and women become more proactive about their reproductive health.

“It’s invisible,” she says. “People don’t talk about it. You talk about, ‘Oh, I’ve got a high cholesterol measure,’ or ‘My blood pressure’s up.’ But you never would say, ‘My egg count is down,’ or ‘My sperm count is down.’”

Richardson agrees that the effect of reproductive toxins on fertility deserved further investigation. “To say that we think these are alarmist and apocalyptic claims, and they’re not well founded, is not to say that we think it isn’t an important research agenda,” she says. “There is a need to centre on men’s reproductive health and understand their bodies as reproductive and as porous to the environment as anyone’s bodies.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments