Fabella: Bone thought to be lost to evolution mysteriously returning to human body

'We are taught the human skeleton contains 206 bones, but our study challenges this'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A primordial bone found in our primate ancestors but thought to be redundant and rapidly dwindling in humans appears to have made a quiet comeback over the past century

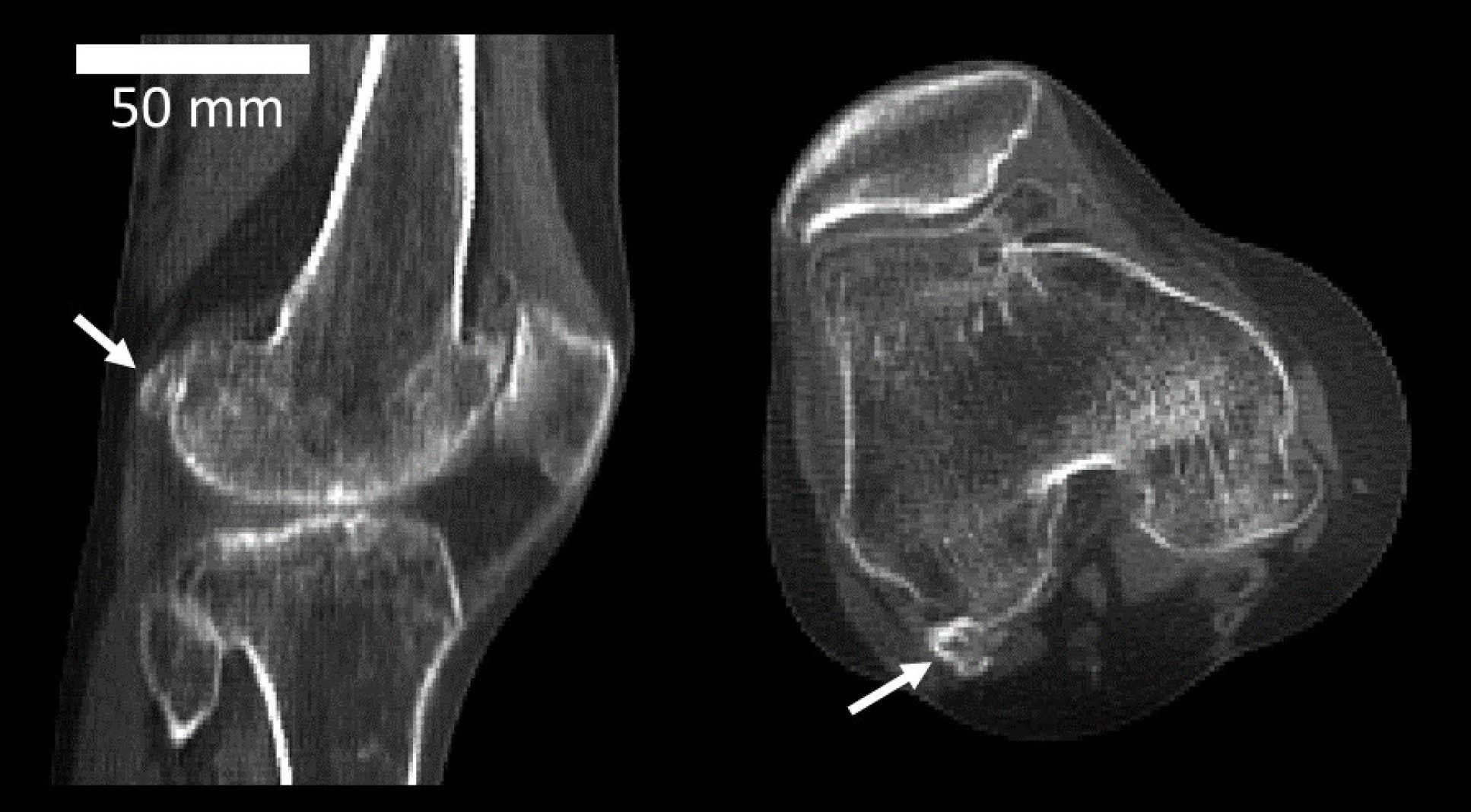

Scientists from Imperial College London have admitted they are stumped as to why the fabella, a small bone buried in a tendon behind the knee, is now three times more common than it was in the early 1900s.

They speculate that its re-emergence could be linked to joint problems, and understanding why could help treat or protect those most at risk.

“We don’t know what the fabella’s function is – nobody has ever looked into it,” lead author Dr Michael Berthaume, said.

“We are taught the human skeleton contains 206 bones, but our study challenges this. The fabella is a bone that has no apparent function and causes pain and discomfort to some and might require removal if it causes problems.”

People with osteoarthritis of the knee are twice as likely to have a fabella, and its presence can interfere with joint operations, but it is not clear if the tiny bone is the cause – or a symptom – of joint problems.

Dr Berthaume likened it to the appendix, another potentially harmful vestigial organ. But unlike the appendix, which is shrinking in humans but is larger in other mammals, fabellae are becoming more common.

The findings, published in the Journal of Anatomy, come from over 21,000 scientific articles, detailing the physiology of 21,676 knees in in 21 countries over the past 150 years.

It shows that in 1918, 11.2 per cent of the world’s population had fabellae, but today that has risen to 39 per cent – a 3.5-fold increase.

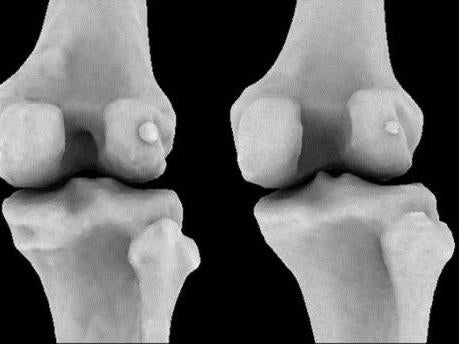

Fabellae are sesamoid bones, which means they grow in the tendon of a muscle – the knee cap being the largest example in the human body.

In monkeys the fabellae can act as a secondary knee cap, increasing the potential leverage and mechanical force, but it began to disappear in apes and early humans.

Dr Berthaume and colleagues speculate that it could be the shifting forces on the knee cap that are behind its comeback.

“The average human, today, is better nourished, meaning we are taller and heavier,” he said

“This came with longer shinbones and larger calf muscles – changes which both put the knee under increasing pressure. This could explain why fabellae are more common now than they once were.”

However as they occur in all groups around the world, but only in some individuals, there is likely to be more to understand in our genetics to piece together its recurrences.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments