Exclusive: The three-parent baby trap - is new IVF technique safe?

Britain is set to become the first country in the world to allow a procedure that promises to prevent inherited disorders being passed on. But from the US comes a warning that we may be acting prematurely

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Plans to allow the creation of so-called “three-parent” in vitro fertilisation (IVF) babies as early as next year are premature because of unresolved safety concerns about the future health of the children, a senior science adviser has warned.

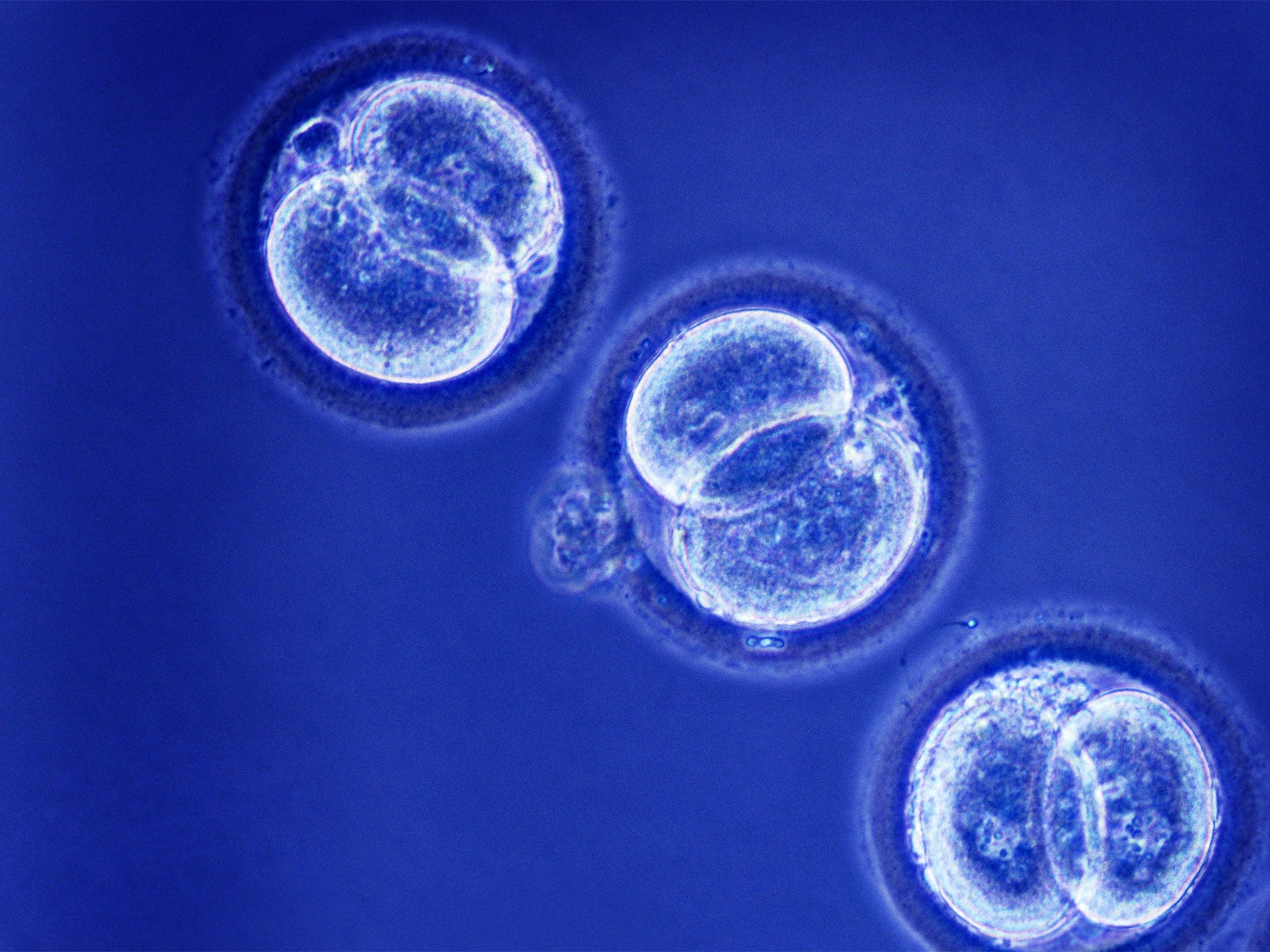

The UK is poised to become the first country in the world to allow the creation of IVF embryos by merging the genetic material of two egg cells in order to prevent the transmission of mitochondrial disorders.

But the United States has decided it is still too early to permit the procedure, said Professor Evan Snyder, who chairs the scientific panel advising the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on mitochondrial transfer.

He said there are still too many safety issues to allow the first clinical trials of the technique in America – and by implication in Britain, where the Government’s own scientific advice is that the technique is “not unsafe”.

Parliament is expected to vote soon on whether to change the law and allow the mitochondrial transfer procedure in the UK, which could pave the way for researchers at Newcastle University to create the first “three-parent” IVF embryos by merging the genetic material of two eggs and a sperm as early as next year.

However, speaking to The Independent, Professor Snyder said that it could take several more years of research to finalise the checks needed to ensure that the transfer of mitochondrial genes from a donor egg into a recipient egg will conform to the FDA’s rules on the safety of clinical trials.

“The FDA panel was not in any way antagonistic towards this intervention. The diseases are terrible, the treatments are non-existent and the technology so far is a tour de force,” Professor Snyder said. “However, everybody concluded that there is still more work to be done.

“There needs to be a little more in vitro work, there needs to be some more animal work, there needs to be longer-term follow-up on the offspring born from monkeys and probably other animals that have reproductive systems similar to humans’,” he said.

“We estimated how much time it would take to fill in these pre-clinical gaps and it looked like it could be anywhere from two to five years. Two years if things go well, five years if they go slower,” Professor Snyder said.

“By two years I mean that is when the pre-clinical data could be available and then that would need to be assessed. The gap I’m talking about is about how much pre-clinical scientific work needs to be done before scientists or someone on the FDA would feel comfortable that we’re assured of safety and efficacy,” he added.

About one in every 6,500 babies born each year is affected by inherited defects in the genes of the mitochondria, microscopic bodies in the cell cytoplasm that generate the energy needed to power each cell of the body.

There are 37 genes of the mitochondria, just 0.2 per cent of the total number of genes in the human genome, and they are inherited solely through the eggs of the mother.

Fewer than 100 families in Britain are thought to be considering mitochondrial transfer as a way of ensuring that their own biological children are free of the disorders. A few are actively seeking the treatment at Newcastle when the law allows it.

Asked whether it would be justifiable to permit the procedure to go ahead on compassionate grounds for affected families who are desperate to have children free of the disease, Professor Snyder said it should not be allowed until all the extra research is completed.

“I don’t think that would [be permissible]. There are alternative ways of preventing the passage of mitochondrial diseases to your offspring that are much less invasive and much more certain,” he said.

“It must be remembered this is not a treatment. If it were a treatment, then certainly the barrier would be different, because these are terrible diseases and you want to make the lives of these children much better. This is a way of preventing the passage of diseases within a family and, quite frankly, there are other ways of doing that,” he said.

“There are other methods of assisted reproduction that can prevent transfer. One could use donor eggs and the father’s sperm and, yes, this would not be the eggs from the mum, so it would not be a genetic mum, but on the other hand it would not quite be adoption because it would involve a genetic component from one of the parents,” Professor Snyder explained.

“I think even if a family insisted that they needed to have this and couldn’t wait for the data to come out affirming safety and efficacy, I’m pretty certain that, in the US, if they were to go through the proper regulatory channels, that would not be granted,” he said.

One of the outstanding issues that need to be addressed is whether the transfer of the mitochondrial genes from one egg to another will interfere with the rest of the human genome in the chromosomes of the cell nucleus – which might cause unintended serious side effects for the children.

“Could you completely divorce the effects of mitochondrial DNA and nuclear DNA and any interaction that may be unanticipated? That was one of the areas of basic science that needed to be investigated. It has not been explored, certainly not in primates or mammals,” Professor Snyder said.

Mitochondria are passed on only through the maternal line so some scientists have suggested that only male IVF embryos should be implanted, to prevent potential damage to future generations

“We don’t know whether these changes will be passed to future generations. That’s one of the studies we need to look at. One of the questions raised is whether the initial studies should only be done in male offspring until the whole issue can be studied more,” Professor Snyder explained.

“One of the issues was that, if we were going to have clinical trials, should they be confined to male offspring? The consensus was probably not, but we have to have ways of looking at passages from generation to generation,” Professor Snyder added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments