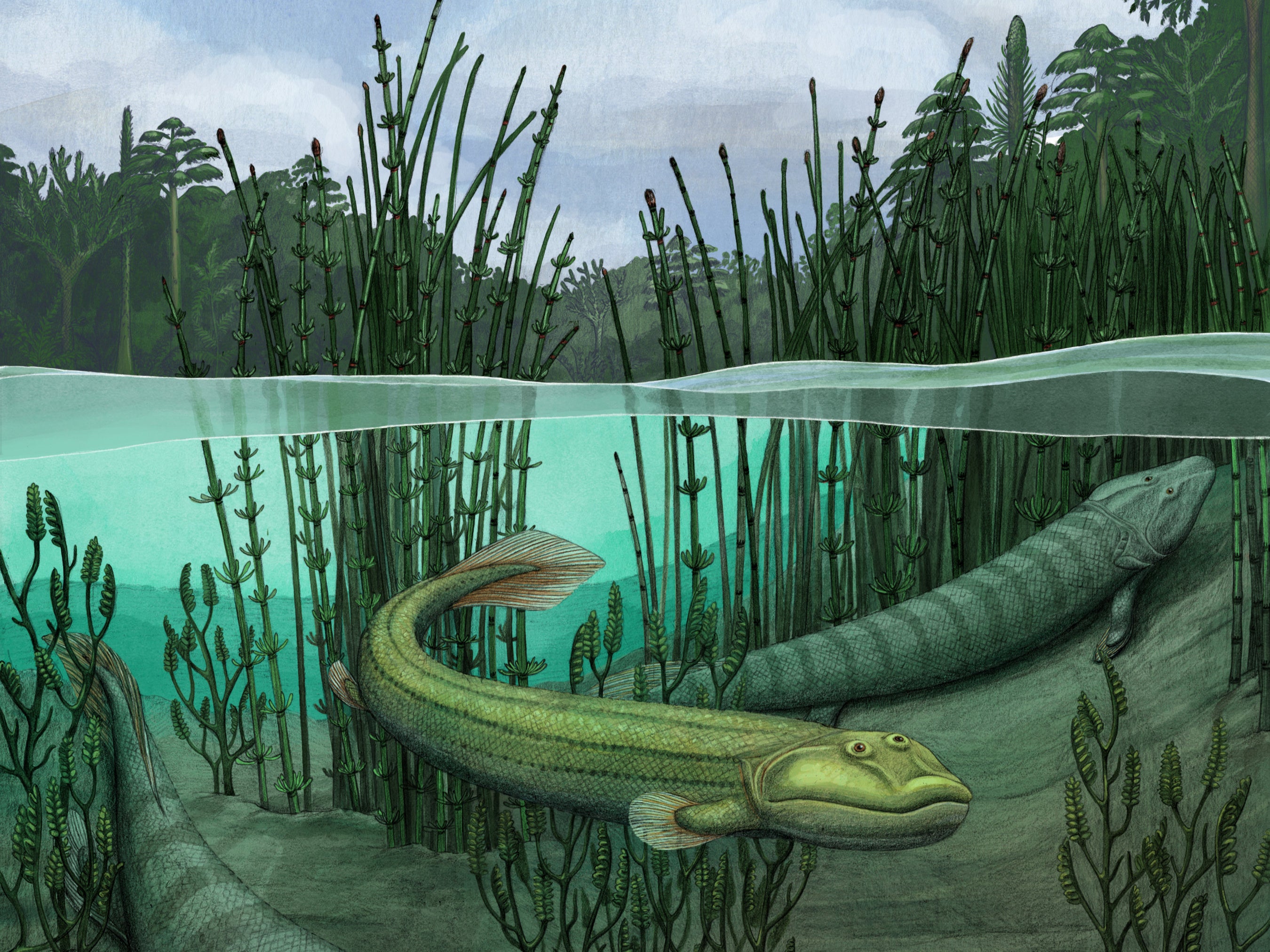

This ‘fishapod’ rejected life on land to return to the water 375 million years ago

Surprise discovery in neglected rock sample ‘blew our minds’, scientists say

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Some 375 million years ago, a small alligator-like creature eschewed the promise of adventure and a new lifestyle on land in favour of its familiar aquatic home.

Qikiqtania wakei is a newly discovered species of “fishapod” described by scientists after its fossil sat in storage for years while other, more glamorous “missing links” were investigated.

The animal displays characteristics of both fish and tetrapods – creatures with the four-limbed body plan shared by all land-based vertebrates.

However, experts say in a new study that its stubby legs were more suited to swimming than walking.

The specimen predates the well-known Tiktaalik roseae, which is considered a potential ancestor for land creatures.

At just 30in Qikiqtania was small compared to Tiktaalik, which could grow up to 9ft. Both were unearthed in the Canadian Arctic.

Qikiqtania was identified from parts of its upper and lower jaws, portions of the neck and scales.

Mostly importantly, a complete pectoral fin with a distinct limb bone called the humerus lacks the ridges that would indicate where muscles and joints would be for walking.

Instead, Qikiqtania’s upper arm was smooth and curved, more suited for a life underwater.

The uniqueness suggests it returned to paddling after its ancestors began to use their appendages for walking.

Lead author Professor Neil Shubin, of the University of Chicago, said: “At first we thought it could be a juvenile Tiktaalik, because it was smaller and maybe some of those processes hadn’t developed yet.

“But the humerus is smooth and boomerang shaped and it doesn’t have the elements that would support it pushing up on land. It’s remarkably different and suggests something new.”

He found the new species days before discovering Tiktaalik about a mile away on southern Ellesmere Island in the territory of Nunavut in northern Arctic Canada.

The name Qikiatania comes from the Inuktitut word Qikiqtaaluk or Qikiqtani, the traditional name for the region where the fossil site is located.

The specimens were collected from a quarry after spotting a few promising looking rocks with distinctive, white scales on the surface.

But they sat in storage, mostly unexamined, while the team focused on preparing Tiktaalik.

Nearly 15 years later, they CT-scanned one of the larger rocks and realised it contained a pectoral fin.

But it was too deep inside to get a high-resolution image, and they couldn’t do much more once the pandemic forced labs to close.

Co-author Dr Justin Lemberg said: “We were trying to collect as much CT-data of the material as we could before the lockdown, and the very last piece we scanned was a large, unassuming block with only a few flecks of scales visible from the surface.

“We could hardly believe it when the first, grainy images of a pectoral fin came into view.

“We knew we could collect a better scan of the block if we had the time, but that was 13 March, 2020, and the university shut down all non-essential operations the following week.”

In the summer of 2020 when campus facilities reopened, they contacted Prof Mark Webster who had access to a saw that could trim pieces off the specimen.

The researchers carefully marked the boundaries on the block and arranged an exchange outside their lab in Culver Hall.

The resulting images revealed a nearly complete pectoral fin and upper limb, including the distinctive humerus bone.

Prof Shubin said: “That’s what blew our minds. This was by no means a fascinating block at first.

“But we realised during the Covid lockdown when we couldn’t get in the lab that the original scan wasn’t good enough and we needed to trim the block.

“And when we did, look at what happened. It gave us something exciting to work on during the pandemic. It’s a fabulous story.”

Qikiqtania is slightly older than Tiktaalik, but not by much. Analysis of where it sits on the tree of life places it, like Tiktaalik, adjacent to the earliest creatures known to have finger-like digits.

But even though Qikiqtania’s distinct pectoral fin was more suited for swimming, it was not entirely fish-like either.

Its curved paddle shape was a distinct adaptation, different from the jointed, muscled legs or fan-shaped fins seen in tetrapods and fish today.

There is a tendency to think animals evolved in a straight line that connects their prehistoric forms to some living creature today, but Qikiqtania shows that some animals stayed on a different path that ultimately did not work out.

Co-author Dr Tom Stewart said: “Tiktaalik is often treated as a transitional animal because it’s easy to see the stepwise pattern of changes from life in the water to life on land.

“But we know in evolution things aren’t always so simple. We don’t often get glimpses into this part of vertebrate history.

“Now we’re starting to uncover that diversity and to get a sense of the ecology and unique adaptations of these animals. It’s more than simple transformation with just a limited number of species.”

Qikiqtania is described in the prestigious British journal Nature.

SWNS

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments