Immigrants have been 'moving and mixing' across Europe since ancient times, groundbreaking DNA research reveals

‘The assumption that present-day people are directly descended from the people who always lived in that same area is wrong almost everywhere,’ says study author

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Groundbreaking research into the DNA of early Europeans has allowed unprecedented insight into the movement of people and cultures across the ancient world.

Carried out by a large team of scientists from several international institutions, the ambitious genetic analysis of hundreds of human specimens from the Neolithic period, Copper Age and Bronze Age represents a fundamental challenge to traditional views about migration throughout history.

“There was a view that migration is a very rare process in human evolution,” said the study’s leader, Dr David Reich, a researcher at Harvard Medical School who specialises in genetics and human history.

The new analysis suggested this could not be further from the truth, he added.

“The orthodoxy – the assumption that present-day people are directly descended from the people who always lived in that same area – is wrong almost everywhere,” he said.

The research contradicts widely held assumptions about European countries’ supposedly “indigenous” populations, claims frequently used by a growing number of prominent populist politicians across the continent to justify anti-immigration policies.

Two papers authored by large, multidisciplinary teams spanning dozens of international institutions unravelled the genetic history of the ancient inhabitants of north-west and south-eastern Europe.

Taken together, this research represents the largest study of its kind to date, more than doubling the number of ancient human genomes that have been sequenced.

“When we look at the data, we see surprises again and again and again,” said Dr Reich, who described the study as a “coming of age” for the discipline of ancient DNA research.

It comes in the wake of DNA analysis of the 10,000 year-old Cheddar Man, Britain’s oldest complete human specimen.

Researchers found evidence he had “dark to black” skin, a discovery heralded by experts as another reminder that human history is characterised by migration.

Cheddar Man’s ancestors were thought to have originally migrated to Europe from the Middle East after the Ice Age.

Both of the new DNA studies were published in the journal Nature. They were welcomed by other scientists.

Dr John Novembre, a computational biologist at the University of Chicago who works in this field but was not involved in the latest papers, said the findings supported the emerging idea that “populations are moving and mixing all the time”.

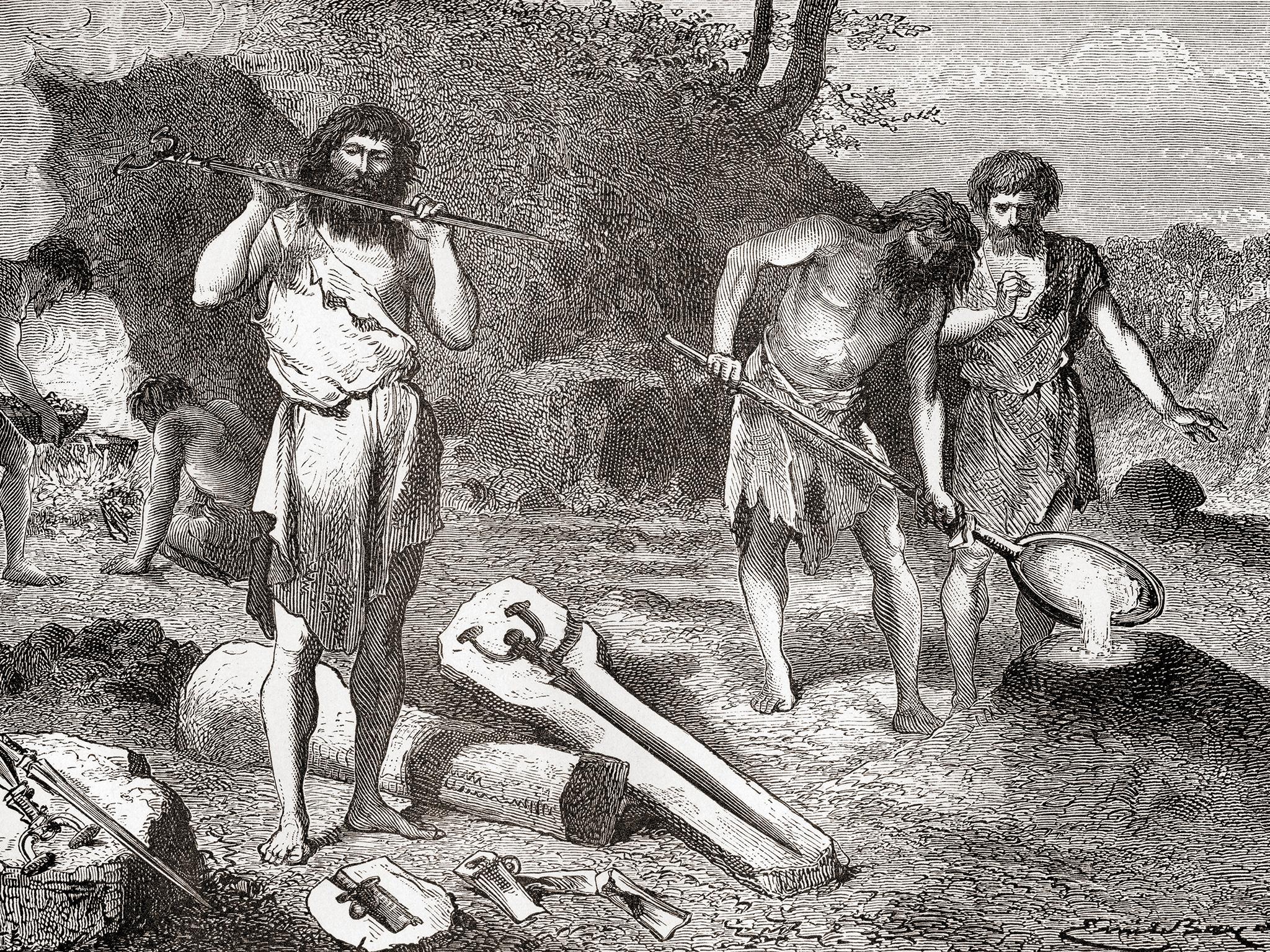

Historically, scientists have only been able to learn about ancient humans by analysing the bones and artefacts they left behind.

But the process of sifting through the wealth of ancient genetic information gleaned from well-preserved ear bones allowed Dr Reich and his team to extract the stories of how humans migrated across ancient Europe.

The people of the so-called “Beaker Culture”, for example, have always been known for the distinctive pots that gave them their name.

While the pots have been found around much of western and central Europe, it has historically been unclear whether this spread was a result of the movement of people, or merely the spread of culture.

By analysing the genomes of over 400 individuals – many of which had been buried with distinctive objects tying them to the Beaker Culture – the scientists were able to establish how these mysterious ancient Europeans moved and integrated throughout the continent.

In some areas, Beaker Practices spread without the people themselves, but elsewhere the researchers found evidence for mass migrations of people from this ancient culture.

Around 90 per cent of Britain’s population was replaced 4,400 years ago by an influx of Beaker Practitioners, shortly after Stonehenge was constructed. This genetic shift brought in genes for pale skin and lighter eyes.

“The Neolithic people who built Stonehenge – and who had a greater genetic similarity with Neolithic Iberians than with those from Central Europe – almost disappear and are replaced by the populations from the Beaker Culture from the Netherlands and Germany,” said Dr Carles Lalueza-Fox, a palaeogenomics expert at Barcelona’s Institut de Biologia Evolutiva, who co-authored one of the studies.

In the second paper, the researchers analysed the genomes of 225 Europeans who lived between 12,000 and 500 BCE to assess how agriculture first moved with people across southern Europe.

This work revealed waves of migration from Asia during the move from hunting and gathering to agriculture.

Farming appears to have been first introduced by migrants from modern-day Turkey, and south-eastern Europe remained a contact point for different groups as agriculture took hold in Europe.

“Archaeological evidence shows that when farmers first spread into northern Europe, they stopped at a latitude where their crops didn’t grow well,” said Dr Reich. “As a result, there were persistent boundaries between the farmers and the hunter-gatherers for a couple of thousand years.”

The research indicates hunter-gatherer genes that persisted in northern Europeans came primarily from men.

Researchers suggested one reason for this is that farmer women tended to be somehow integrated into hunter-gatherer communities before the men followed.

Professor Barry Cunliffe, an archaeologist at the University of Oxford and co-author of one of the studies, said ancient DNA analysis was poised to revolutionise the field of archaeology, and described their results as “mind-blowing”.

“They are going to upset people, but that is part of the excitement of it,” he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments