Enceladus: What is the 'tiny snowball' in our solar system that might hold alien life?

The little ball of water and ice wasn't even thought to be one of the more interesting of Saturn's moons

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Enceladus is, to many, just an icy snowball floating around in space. But it's just become a lot more important: it's perhaps the greatest hope for life in our own solar system.

The small moon of Saturn, which has a 502km diameter, has been revealed to have hydrothermal processes going on underneath its crust. That, in turn, means that it may have all the requirements for life – and that microbial life might be found there.

What started out as an afterthought or side project for the Cassini mission to Saturn has turned out to be perhaps its crowning glory.

Enceladus is made up of an icy surface shell and a rocky interior inside, with a warm ocean sandwiched between the two. It's in that ocean that any life is likely to live – apparently given fuel by the processes discovered in the new research.

It was first found by British astronomer William Herschel, in 1789. It got its name in 1847, from Herschel's astronomer son John.

Since then, it languished mostly in obscurity – one of a full 53 moons around Saturn and not looking to be even one of the more interesting ones.

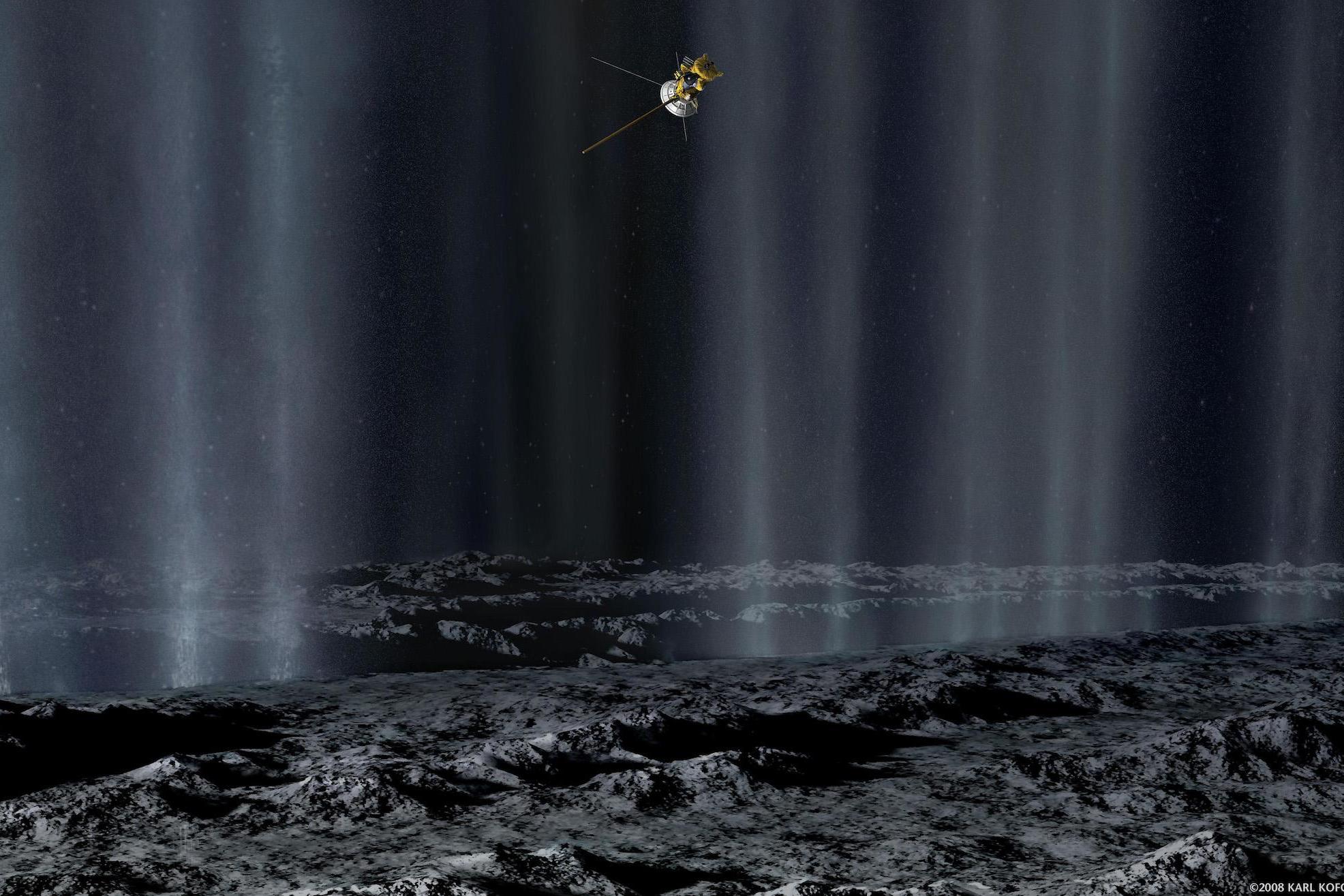

But that all changed when the Cassini orbiter arrived at Saturn in 2005. It found plumes of water shooting out of cracks in Enceladus's surface, leading scientists to wonder whether it might be geologically alive after all.

That led scientists to fly Cassini through the plumes, using all of the various sensing mechanisms on board to try and understand what the plumes were made of.

It found mostly water, or tiny ice particles, with traces of other things like methane, ammonia, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and various salts and simple organic molecules. Later it found silica nanoparticles, suggesting that something was going on between the hot rocky interior and the alkaline water.

That led scientists to expect and hope that hydrogen might be found inside, making the world habitable. That's what the latest flyby – in 2015, when Cassini was shot through the plumes – was looking out for, and what it found.

"What we knew already from Cassini is that Enceladus has these fountains of water jetting out from its surface," said Lewis Dartnell, an astrobiologist from the University of Leicester. "That in itself was a hugely exciting and totally unexpected discovery – it tells us this tiny snowball of a world, smaller than the UK from side to side, is geologically active.

"It’s warm on the inside, where there’s a large body of liquid water. We knew there was an environment, which was potentially habitable, in Enceladus. But Cassini has essentially tasted what’s in that water."

It's what it tasted there that has got scientists so excited: molecular hydrogen, suggesting that the moon has fuel for life. With that, it completes the three things – alongside water and organic molecules – that are required to support living things.

But it's just the latest surprise from the little moon, which was never intended to be a significant object of study for the Cassini mission.

"When Cassini got there it was not a major target of the mission," says Caitriona Jackman from the University of Southampton. "It was thought just to be a rocky or icy moon. It was at the beginning of the mission in 2005 when it had a flyby and realised there was more than meets the eyes."

Gradually, the truth about the moon was revealed: strange magnetic effects were pinned down to "tiger stripes" on the crust, and water vapour and other organic material was shooting out of its vents.

"Enceladus has been the biggest bonus ever," says Professor Jackman, who worked on the Cassini mission. "It was an incredible discovery to even know that it was interesting. It wasn’t a highlight or a major target, but it turns out to be one of the most interesting of Saturn's moons."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments