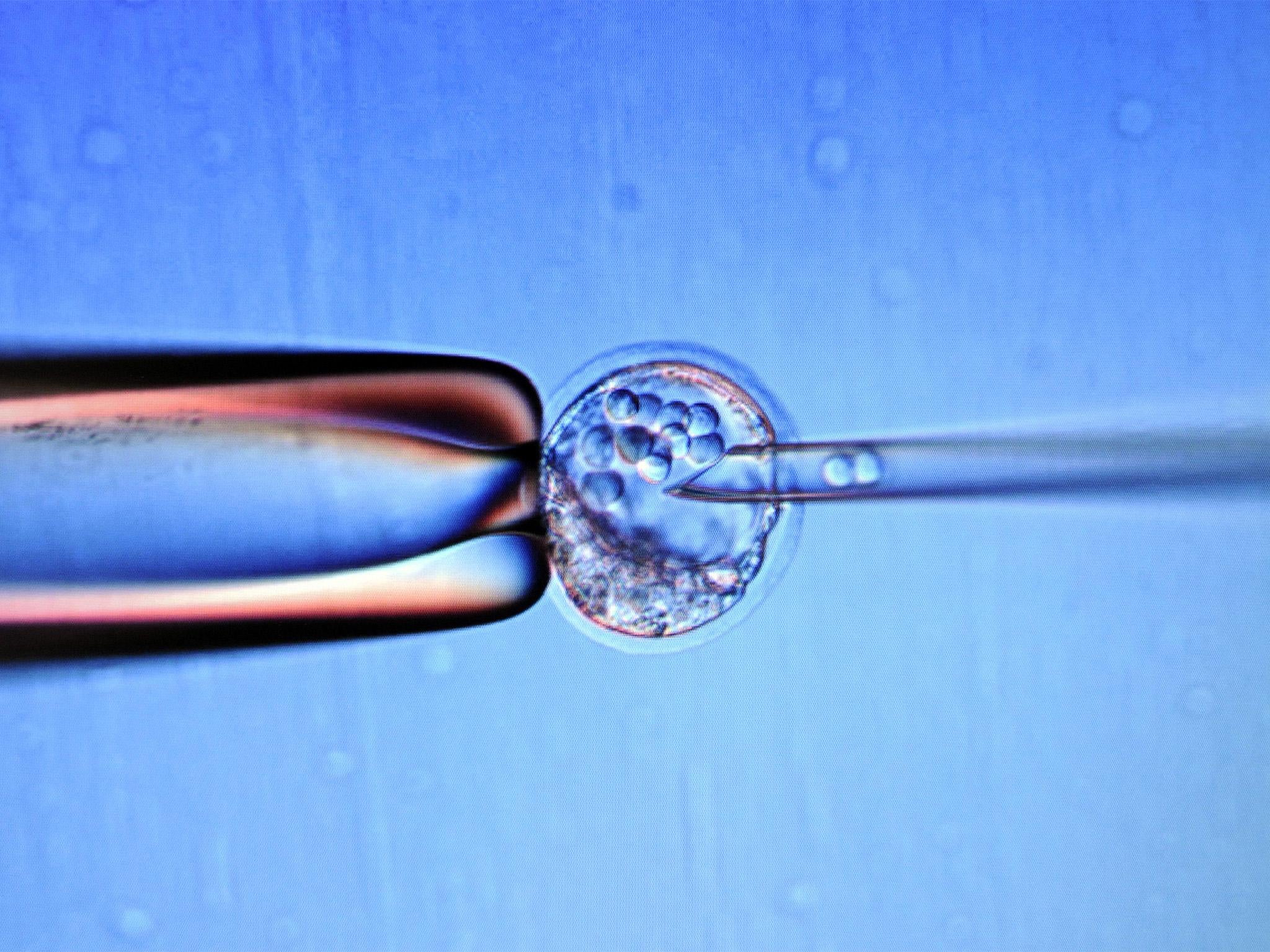

Embryo cell abnormalities not necessarily a sign that a baby will be born with a birth defect, study finds

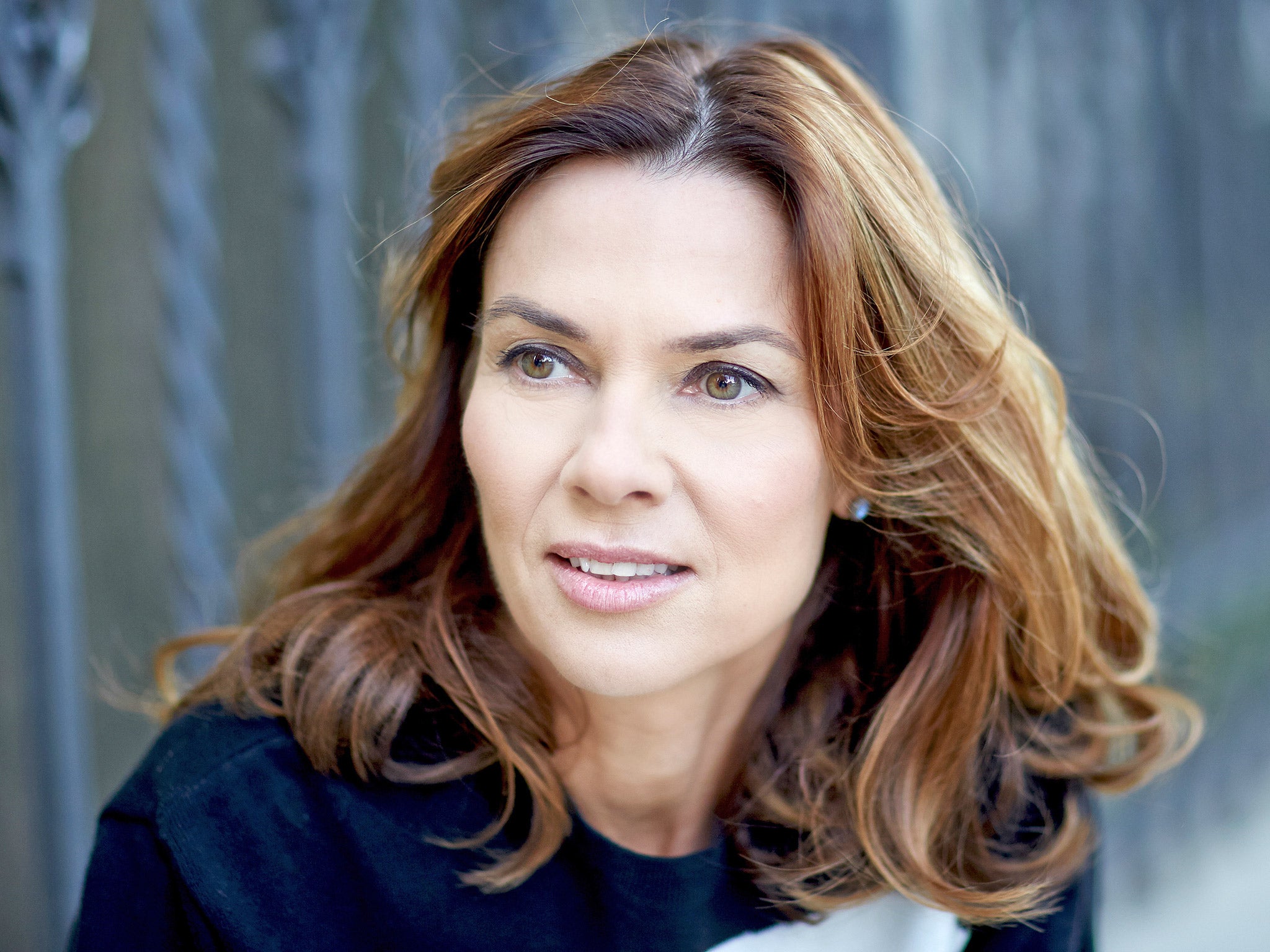

Professor Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz began her study after a test carried out while she was pregnant discovered a trisomy in chromosome 2 - the second largest human chromosome

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An academic who became pregnant with her second child, aged 44, has shown that abnormal cells in the early embryo are not necessarily a sign that a baby will be born with a birth defect such as Down’s syndrome.

Professor Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, who describes herself as one of the growing number of women having children over the age of 40, was moved to tears following a CVS test, carried out early on in pregnancy to ascertain embryo normality using cells taken from the placenta.

It discovered a trisomy, in which there are three instances of a particular chromosome instead of the normal two, in chromosome 2 - the second largest human chromosome. Dozens of diseases and traits are related to genes located in chromosome 2 including autism, deafness and diabetes.

“It was not good news,” Professor Zernicka-Goetz told The Independent. “Most people have heard of Trisomy-21, which results in Down’s syndrome, but chromosome 21 is much smaller than chromosome 2, so not many children with Trisomy-2 will be able to have a normal life.

“It was an enormous shock, despite the fact I’m a scientist and would be seen as a very rational, logical person. I was in turmoil and, indeed, I had tears in my eyes, which doesn’t happen that often.”

She asked geneticists about the potential implications for the baby but, as so little research has been carried out in this area, they were at a loss to provide further information.

“I quickly realised very little is known about what happens to those abnormal cells within our embryos, but because the CVS test is from the placenta it does not mean that the embryo will also have the same number of abnormal cells.”

Inspired by her own experience, Professor Zernicka-Goetz and her team at the University of Cambridge spent the next year developing a model using mice to discover the fate of the abnormal cells found in the placenta. They wanted to discover the minimum amount of normal cells needed in an embryo for it to develop into a normal, healthy baby.

In embryos where the mix of normal and abnormal cells was half and half, the abnormal cells within the embryo were killed off by apoptosis, or “programmed-cell death”, even when placental cells retained abnormalities. This allowed the normal cells to take over, resulting in an embryo where all the cells were healthy.

When the mix of cells was three abnormal cells to one normal cell some abnormal cells continued to survive, but the ratio of normal cells increased.

“I couldn’t be happier when we found the result,” Professor Zernicka-Goetz said of the research, published on Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications. “It was absolutely unbelievable and what I hope will be the major message for mothers like me.”

Fortunately her second child, Simon, was born healthy while her study continued. “I know how lucky I was and how happy I felt when Simon was born healthy,” she said. “Many expectant mothers have to make a difficult choice about their pregnancy based on a test whose results we don’t fully understand.”

Her team will now try to determine the exact proportion of healthy cells needed to completely repair an embryo and the mechanism by which the abnormal cells are eliminated.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments