The skull that proves modern humans arrived in Europe 150,000 years earlier than thought

Crania found in Greek cave show Homo sapiens came to Eurasia at least 210,000 years ago

Modern humans arrived in Eurasia more than 150,000 years earlier than thought, scientists have concluded after the discovery of a fossilised skull in a cave in southern Greece.

One modern human and the other Neanderthal, a pair of partial skulls were discovered by the University of Athens in the Apidima Caves in the late 1970s.

They were so fragmented that they could not be accurately described at the time.

But using modern dating and imaging techniques, a team of researchers led by the University of Tubingen in Germany, conducted a new study on the samples.

The results rewrite our understanding of human evolution and show that Homo sapiens reached Europe at least 210,000 years ago.

All humans alive today outside of Africa can trace their ancestry to the main dispersal out of the continent around 50,000 to 70,000 years ago. However, there were several migrations before this that left no DNA trace on the modern population.

The population of modern humans living in southern Greece 210,000 years ago were probably replaced by Neanderthals - as shown by the younger skull found in the cave.

Initially, scientists assumed that because the skulls were found close together they would date to the same period.

“But the more we studied Apidima 1 [the modern human], the less it looked like Apidima 2 and Neanderthal fossils – although only part of the back of the cranium was preserved, it looked like Homo sapiens fossils from the last 100,000 years," said Professor Chris Stringer from the Natural History Museum.

“Now, we know from further dating that this modern human fossil is actually older than the Neanderthal one from the same site.”

Lead researcher, Professor Katerina Harvati, from the University of Tubingen said: “Our results suggest that at least two groups of people lived in the Middle Pleistocene, in what is now southern Greece: an early population of Homo sapiens and, later, a group of Neanderthals. It’s a complicated scenario. The early modern humans in Greece were replaced by Neanderthals. It was not one exodus out of Africa but lots of small ones.”

The research, published in the journal Nature, supports the hypothesis that early modern humans spread out of Africa, where they evolved multiple times.

This group was probably wiped out by environmental factors – which could have included climatic events and pressure from Neanderthals.

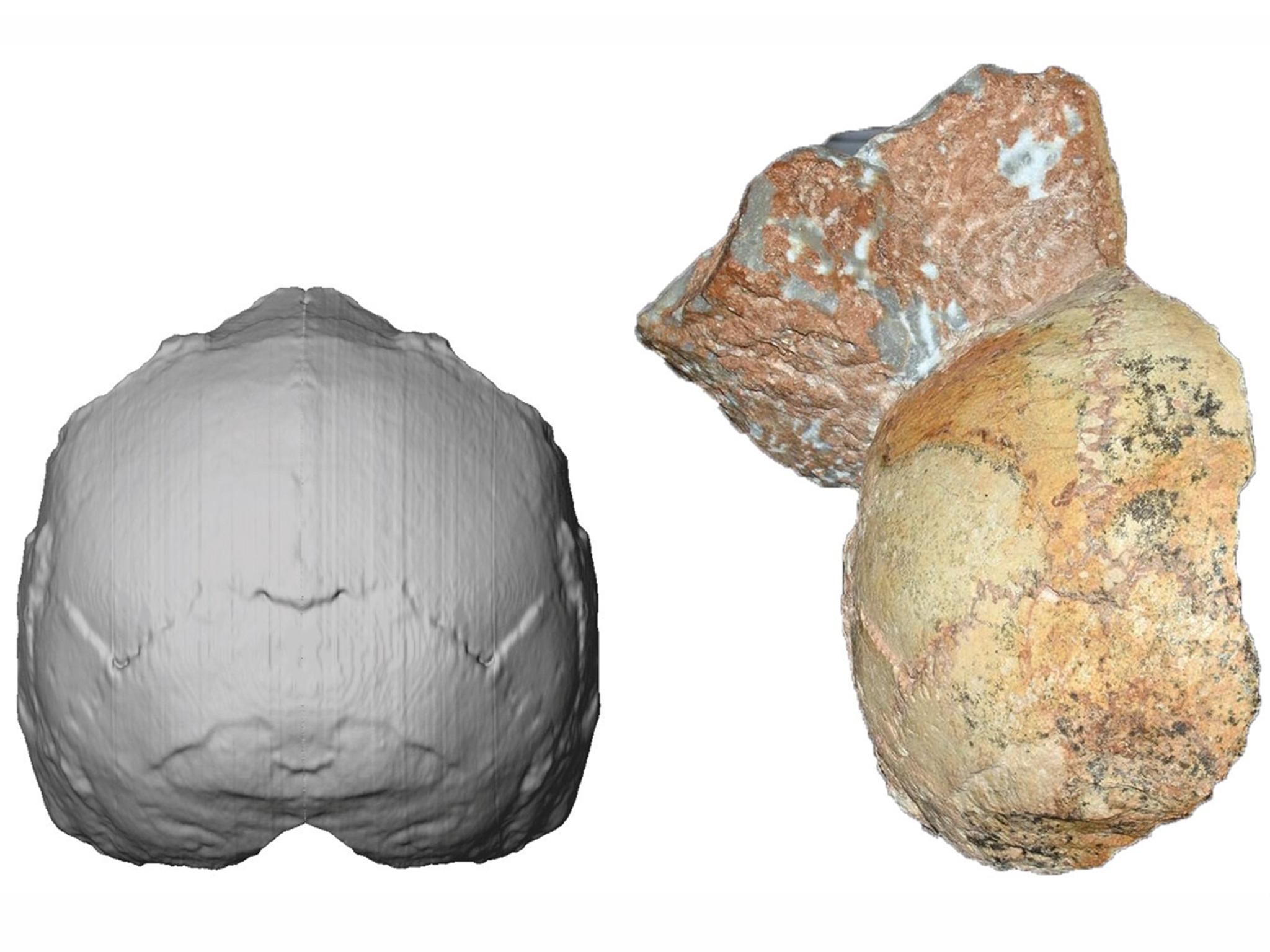

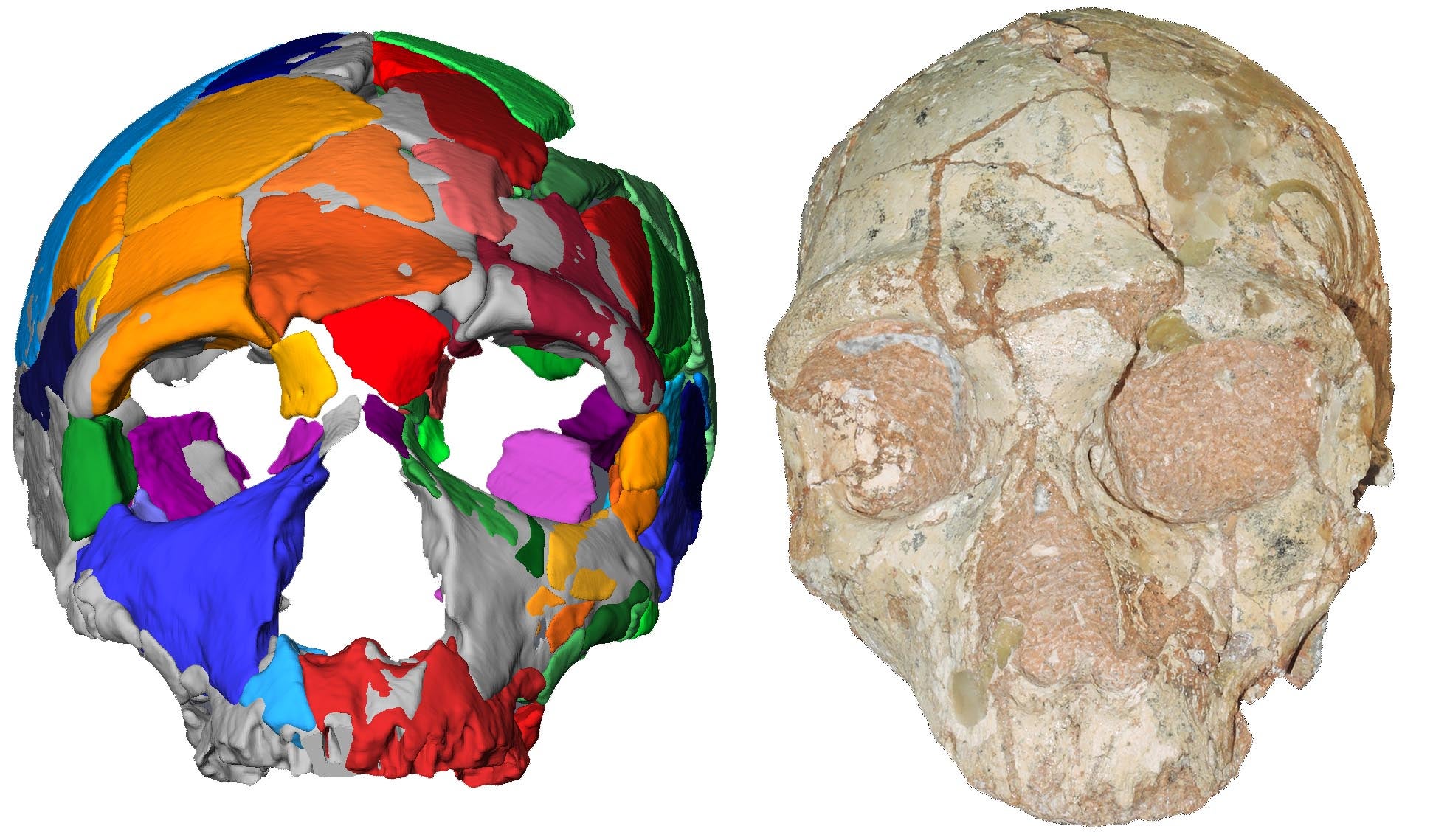

Reconstructions of the Apidima 1 cranium revealed a high and rounded shape – a unique feature of modern humans which contrasts sharply with Neanderthals.

Researchers conducted numerous comparisons with different human fossils, using a highly accurate radiometric dating method to determine their age. They also used virtual reconstructions of the damaged parts of the skulls to discover more about the origins of the fossils.

This discovery is the latest piece in the jigsaw of human evolution which is continually changing in light of new research.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks