Dr Seuss: Scientists may have figured out what makes the writer's work so funny

And it isn't what you think

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Chris Westbury was trying to get work done, and everyone around him kept laughing.

As part of a study on aphasia, a speech and language disorder, the University of Alberta psychology professor was running a study in which test subjects were shown strings of letters and asked to distinguish real words from made-up ones. But every time the (non) word “snunkoople” cropped up, the subjects would collapse with mirth.

Westbury may be an academic, but he’s one with a sense of humor. So when the aphasia project ended, he turned his attention to a new research topic: What makes “snunkoople” so funny?

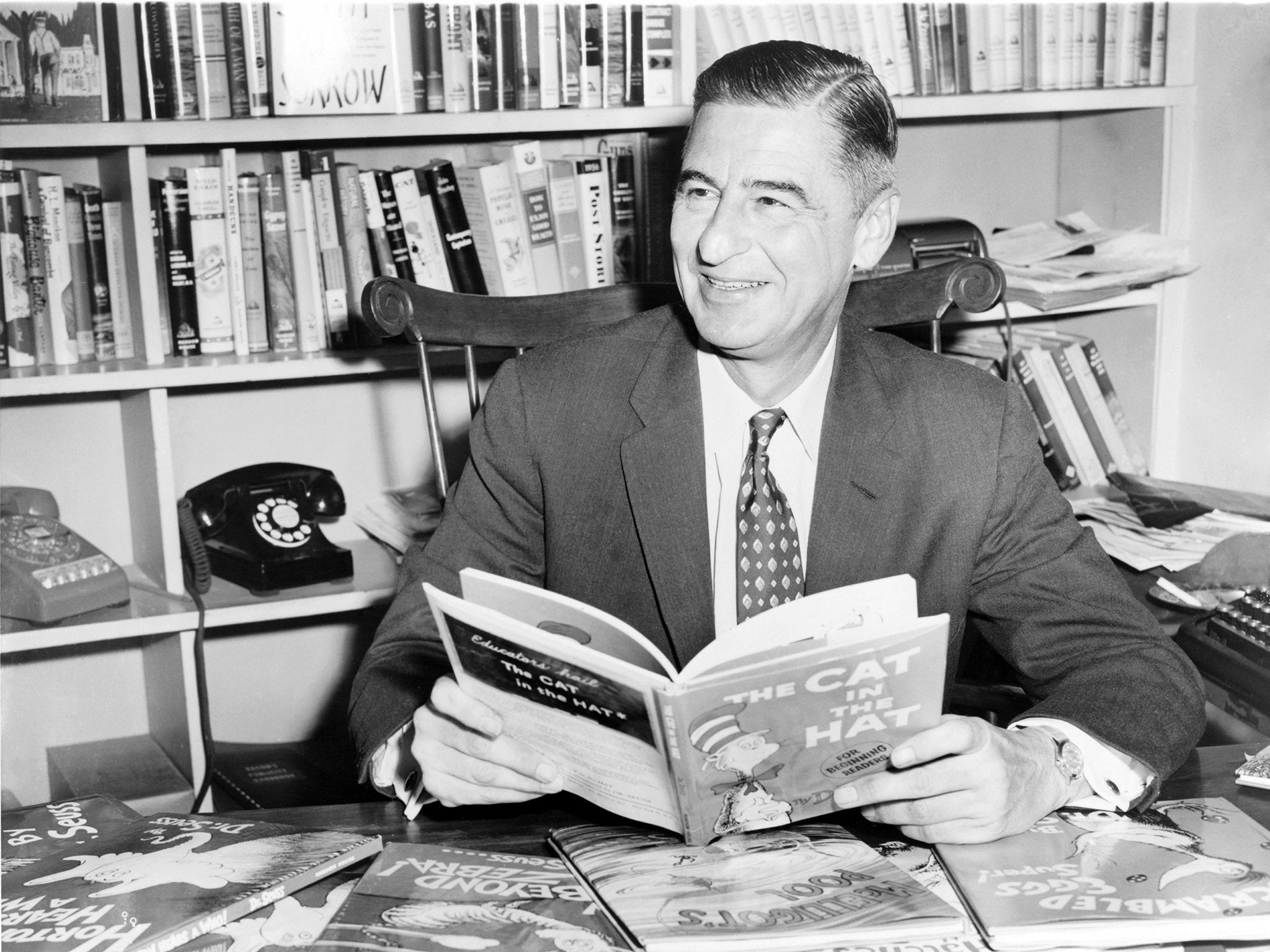

His conclusions, which will be published in the January 2016 issue of the Journal of Memory and Language, form the first ever “quantifiable theory of humor,” Westbury said in a press release. It explains not just the hilariousness of “snunkoople,” but the enduring genius of the world’s wittiest made-up wordsmith, Dr. Seuss.

The theory gets its inspiration from two decidedly un-funny sources: the 19th century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, and math.

Schopenhauer is better known for establishing a philosophy called “Pessimism” than theorizing on the principles of humor. But he apparently did find time to jot down some thoughts on comedy, among them, the idea that things are funny when they violate our expectations. This idea, termed “incongruity theory,” explains why people laugh at puns and the sight of a dozen clowns clambering out of a teeny, tiny car — both defy what we expect to hear or see.

This probably held true for funny words too. An unusual non-word like “snunkoople” or Dr. Seuss’s “yuzz-a-ma-tuzz” would be more likely to make people laugh than one that sounds like it could almost be real, like “clester.”

But Westbury and his psychologist colleagues had no way of quantifying incongruity, so they borrowed one from mathematics: Shannon entropy. Theformula, developed by information theorist Claude Shannon, will make your head spin more than a Dr. Seuss run-on-sentence, but the gist is that it quantified how much entropy, or disorder, is contained within a message. Words with unusual or improbable letter combinations — “snunkoople,” “yuzz-a-ma-tuzz,” “oobleck,” “truffula,” “sneetch” (the last four are all Seuss-isms) — are more disordered, and therefore, Westbury hypothesized, funnier.

To test that idea, Westbury, his psychology department colleagues and two linguists from the University of Tübingen in Germany drew up a list of made-up words, some with high degrees of entropy and some with low ones. They asked subjects to compare two words and choose which was funnier, then rate words’ humorousness on a scale from 1 to 100.

Almost always, the more disordered a word, the funnier people found it.

Dr. Seuss, of whom the New York Times once wrote, “Nobody could possibly have ideas in any way resembling those that occur to this talented man,” seemed to recognize that intuitively. When Westbury and his colleagues ran 65 famous Seuss-isms through the entropy formula, Seuss’s terms were reliably more disordered than ordinary English words.

According to Westbury, the theory shows that humor isn’t completely subjective. What we find funny is predictably unpredictable. And though readers may think they’re laughing instinctively at young Gerald McGrew hunting the “Russian palooski” and the “Fizza-ma-Wizza-ma-Dill” in his “skeegle-mobile,” they are actually doing an “unconscious calculation” in their heads about the improbability of those words, Westbury explained onYouTube.

“They’re going on their gut feeling, going ‘It feels funny to me,'” he said. “And we’re showing that feeling is actually a kind of probability calculation. … Emotion is helping us compute the probabilities in the world.”

Even though, according to Westbury, this is the first time a theory like this has been applied to humor, it’s actually not such a radical notion. As far back as the 1920s, researchers have known that there’s a sort of innate sense to the way words work. For example, when asked to match the words “kiki” and “bouba” with shapes, people assign the first to a spiky shape and the latter to a curvy one. This is true whether they’re American undergraduate students or Tamil-speakers in India or toddlers who can’t even read yet. All humans, regardless of their native language, are born with certain expectations for how things should sound.

And when words defy our expectations, Westbury explained in the press release, it makes sense that we respond with laughter.

Many psychologists believe that laughter and amusement evolved to signal that a surprise is not a threat. Peter McGraw, a leading proponent of what’s called “benign violation theory,” told Wired that a laugh is a response to a violation — something shocking, upsetting, or confusing — that turns out not to be so bad. It’s how we show that an off-color comment about 9/11 is just a Sarah Silver joke; that a man tripping up the stairs is just Charlie Chaplin performing slapstick; that a weird, unfamiliar word is just a Dr. Seuss-ism. It’s also how our hunter-gatherer ancestors likely alerted one another that the rustle in the bushes they just heard was a rabbit rather than saber-toothed tiger.

“Organisms that could separate benign violations from real threats benefited greatly,” McGraw said. By laughing, humans can “signal to the world that a violation is indeed OK.”

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments