Diamonds around distant stars responsible for previously unexplained glow in Milky Way could hold clues about early universe

Scientists use 'Sherlock Holmes-like' methods to discover mysterious space radiation comes from spinning nanodiamonds

A mysterious “glow” from space has been traced to tiny spinning diamonds found around stars.

For decades, scientists have been able to see a faint signal of microwave light coming from parts of the night sky.

Known as the anomalous microwave emission (AME), the glow was an unexpected discovery that first emerged when astronomers took measurements of microwave radiation in space at the turn of the 21st century.

Now, after years of speculation about this unusual glow, a team led by Dr Jane Greaves at Cardiff University has finally pinpointed its source.

"In a Sherlock Holmes-like method of eliminating all other causes, we can confidently say the best candidate capable of producing this microwave glow is the presence of nanodiamonds around these newly formed stars," said Dr Greaves.

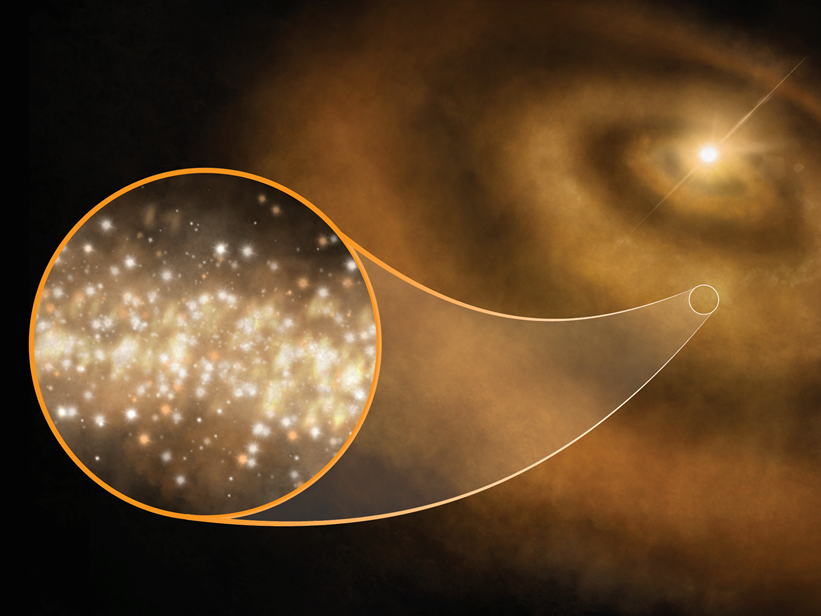

While nanodiamonds are best known as components of meteorites that fall to Earth, these structures were found inside rings of dust and gas surrounding newly formed stars known as protoplanetary discs.

These discs contain the ingredients that ultimately go on to form new planets, and the scorching hot temperatures found inside them provide the perfect conditions for these tiny carbon crystals to form.

Due to a unique arrangement of atoms, nanodiamonds emit radiation as they spin, leading to the glow detected by astronomers on Earth.

As they spin so exceptionally fast, the waves of radiation they emit are small – microwave sized – rather than larger wavelengths that would likely be drowned out by other sources of radiation from space.

To arrive at these conclusions, Dr Greaves and her team zoomed in on three young stars emitting AME light using incredibly powerful telescopes in West Virginia and Australia.

Prior to this it was assumed that some kind of cosmic particle was responsible for the AME effect, but the most likely candidates were dust grains made from molecules called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

However, the scientists were able to take measurements from the stars’ protoplanetary discs and match them with the known infrared signatures of nanodiamonds – confirming them as the source.

They found that the signal specifically matched that given off by nanodiamonds, with layers of hydrogen-bearing molecules on their surfaces.

"This is the first clear detection of anomalous microwave emission coming from protoplanetary disks," said Dr David Frayer, a co-author of the paper and astronomer at the Green Bank Observatory in West Virginia.

These results were published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

"This is a cool and unexpected resolution of the puzzle of anomalous microwaves radiation," said Dr Greaves.

"It's even more interesting that it was obtained by looking at protoplanetary disks, shedding light on the chemical features of early solar systems, including our own."

The scientists also suggest their findings could have implications for those investigating the early days of the universe following the Big Bang.

If the universe expanded very rapidly – faster than the speed of light – a trace of this phenomenon could be found in the background microwave levels in space.

"This is good news for those who study polarisation of the cosmic microwave background, since the signal from spinning nanodiamonds would be weakly polarised at best," said Dr Brian Mason, an astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory who co-authored on the paper.

"This means that astronomers can now make better models of the foreground microwave light from our galaxy, which must be removed to study the distant afterglow of the Big Bang."

Co-author Dr Anna Scaife from the University of Manchester agreed their discovery was "an exciting result".

"It's not often you find yourself putting new words to famous tunes, but 'AME in the Sky with Diamonds' seems a thoughtful way of summarising our research," she said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks