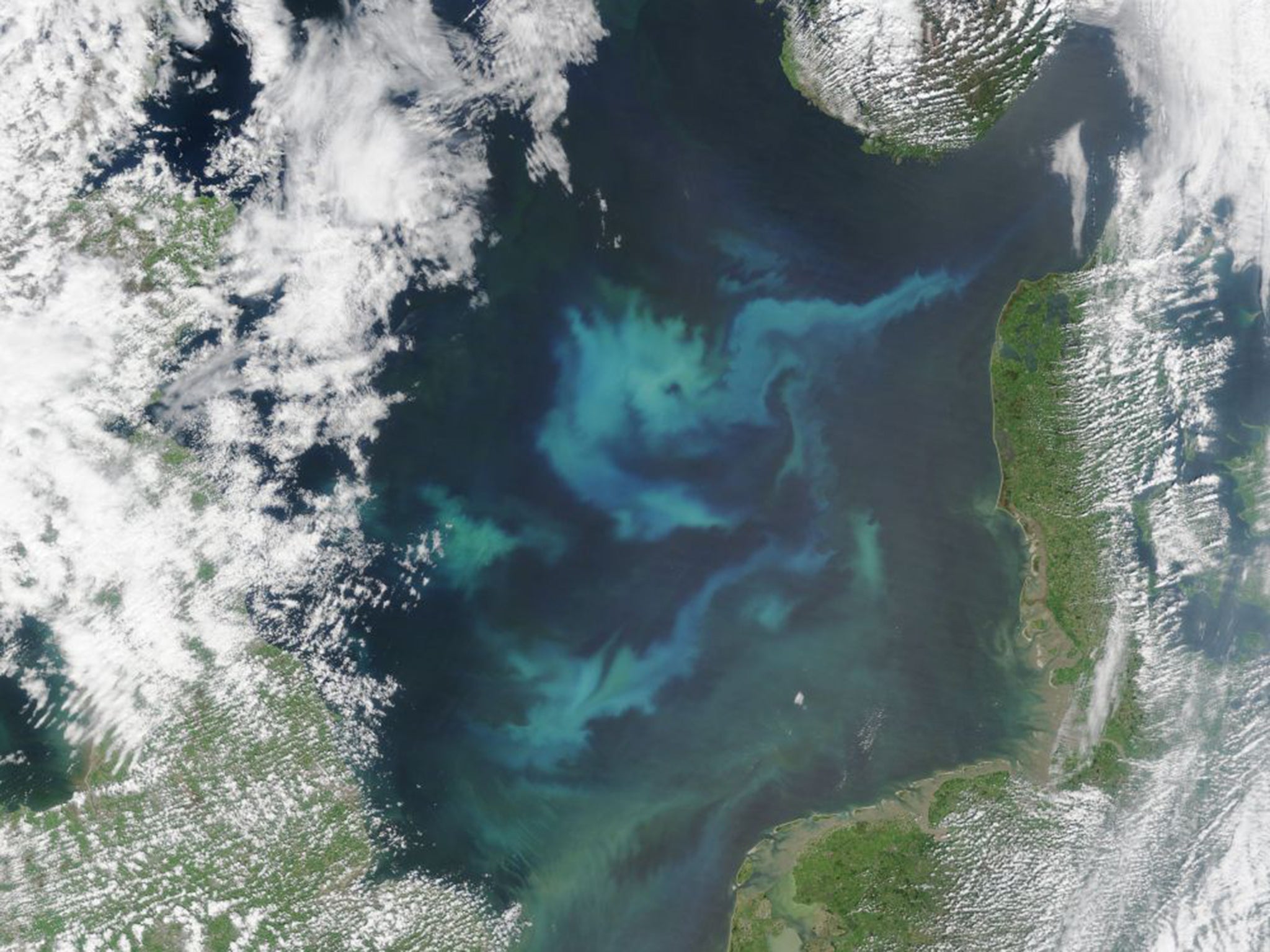

Climate change: Atlantic plankton bloom reflects soaring carbon dioxide levels, scientists say

Scientists say growth of coccolithophores, a microscopic marine alga, could be 'canary in the coalmine' for climate change

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A microscopic marine alga with a shell-like skeleton has increased more than tenfold in the North Atlantic over the past 50 years in response to rising levels of carbon dioxide, scientists have discovered.

The dramatic “bloom” of coccolithophores since the 1960s is unprecedented and marine biologists said they are both astonished and mystified by such a sharp increase in microscopic phytoplankton.

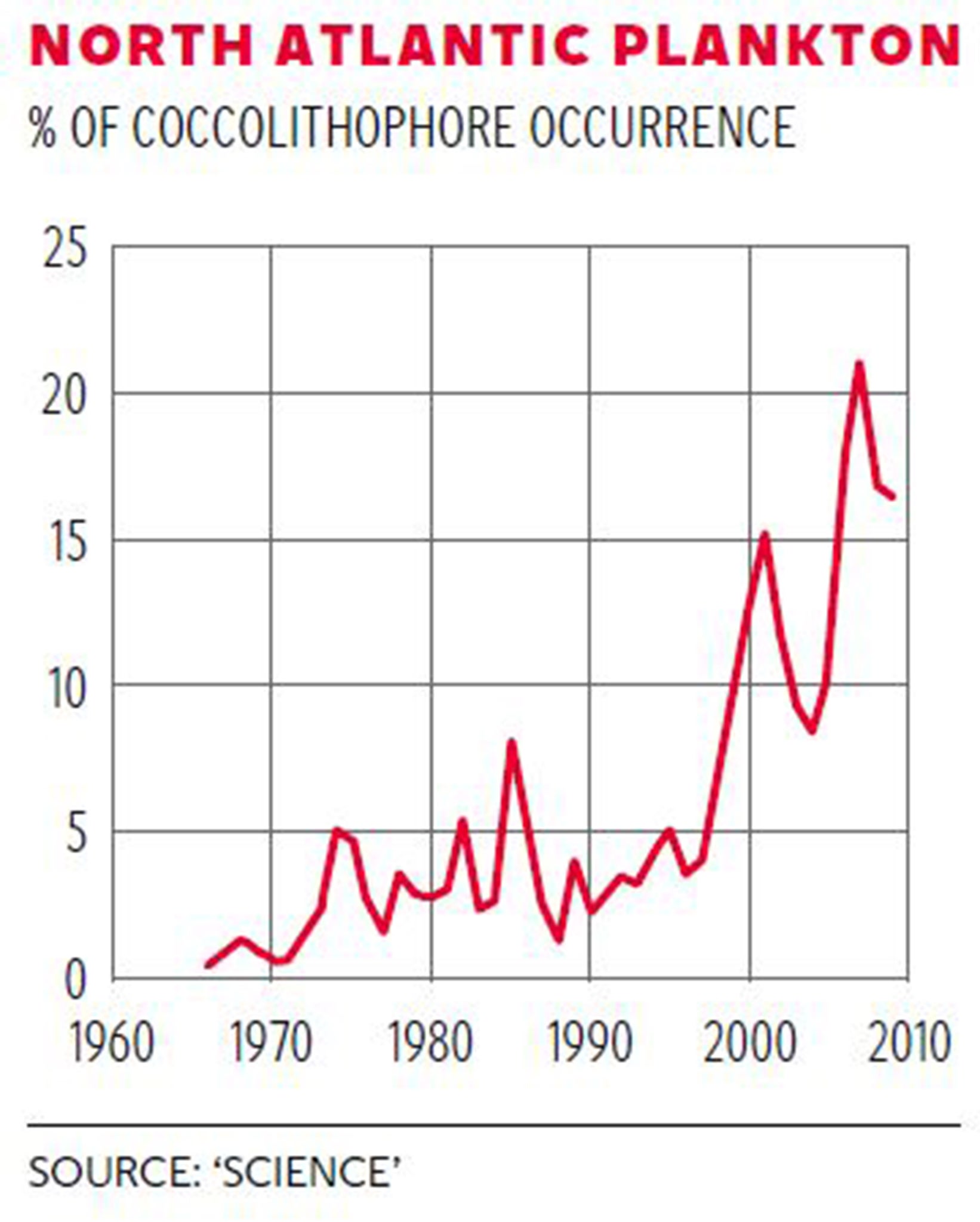

An analysis of more than 81,000 plankton samples collected over the past half century has found that the percentage of coccolithophores has increased from about 2 per cent to more than 20 per cent, with a dramatic acceleration occurring after the late 1990s.

Scientists investigated more than 20 possible causes for the increase and concluded that rising concentrations of carbon dioxide dissolved in the seawater, combined with the ocean currents in the Atlantic, were the strongest candidates.

The simplest explanation is that carbon dioxide is “fertilising” the growth of coccolithophores, a hypothesis supported by dozens of laboratory experiments where the marine algae were grown in various concentrations of dissolved carbon dioxide, the researchers said.

However, no other living organism has been shown to have responded so dramatically in the wild to rising levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and the oceans. This has led the researchers to warn that the phenomenon may have wider implications for the marine ecosystem and the global climate.

“Something strange is happening here, and it’s happening much more quickly than we thought it should,” said Anand Gnanadesikan, a marine scientist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, and co-author of the study.

“What worries me is that we see such a sharp response. Most of the climate models I run show relatively gentle responses of phytoplankton to much larger changes in carbon dioxide – of the order of 10 per cent over the course of this century,” Dr Gananadeskan said.

“So it makes me wonder what we've missed, and whether other surprises in the works may be less benign,” he said.

The dramatic rise in coccolithophores could be an indication that a big climatic shift is underway given that they are associated in the geological record with the warm periods between ice ages, said William Balch of the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Science in Maine, Massachusetts.

“Coccolithophores have been typically more abundant during Earth’s warm interglacial and high CO2 period. The results presented here are consistent with this and may portend, like the ‘canary in the coalmine’, where we are headed climatologically,” Dr Balch said.

“We never expected to see the relative abundance of coccolithophores to increase 10 times in the North Atlantic over barely half a century,” he said.

Coccolithophores

Coccolithophores are tiny marine alga that float in the sea as plankton. They are unusual in forming calcium carbonate shells which eventually sink to the seabed to form chalky deposits – the most famous of which is the White Cliffs of Dover.

Many of the most beautiful medieval cathedrals, such as Chartres and Salisbury, are made of fossilised limestone formed by the deposits of billions of coccolithophore shells over many hundreds of thousands of years.

Coccolithophores are single-celled, photosynthetic organisms encased in shells made of disc-like segments composed of calcium carbonate.

They lie at the base of the marine food chain and their dead shells over many thousands of years form vast chalk deposits on the seabed which eventually became well-known landmarks, such as the White Cliffs of Dover.

Scientists have suggested that chalk-producing marine life, or “calcifers”, could be badly affected by rising ocean acidity, caused by increasing concentrations of carbon dioxide, which forms carbonic acid in seawater.

Coccolithophores appear to be an exception given that they have thrived with rising carbon dioxide and stronger ocean acidification. However, there may come a tipping point later this century when ocean acidity becomes too strong even for coccolithophores to form shells, Dr Gananadeskan said.

“In contrast to oysters and particularly pteropods – the marine snails that are the poster child for ocean acidification – coccolithophores don't appear to need their shells to survive... Basically these results show that there is at least one major chalk-producing organism that isn't currently declining,” he said

The study, published in the journal Science, used a database of continuous plankton recordings gathered by commercial shipping since the 1930s and collated by the Sir Alistair Hardy Foundation for Ocean Science in Plymouth.

Willie Wilson, director of Saphos, said: “Coccolithophores appear to take advantage of higher CO2 levels, forming more extensive blooms of this charismatic organism that can even be seen from space. This is important because it will have changed the dynamics of the ocean food chain in the North Atlantic Ocean and North Sea and this will have knock-on effects to fisheries in these regions.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments