Children receive new ears grown from their own cells in world first

‘They’ve shown that it is possible to get close to restoring the ear structure’

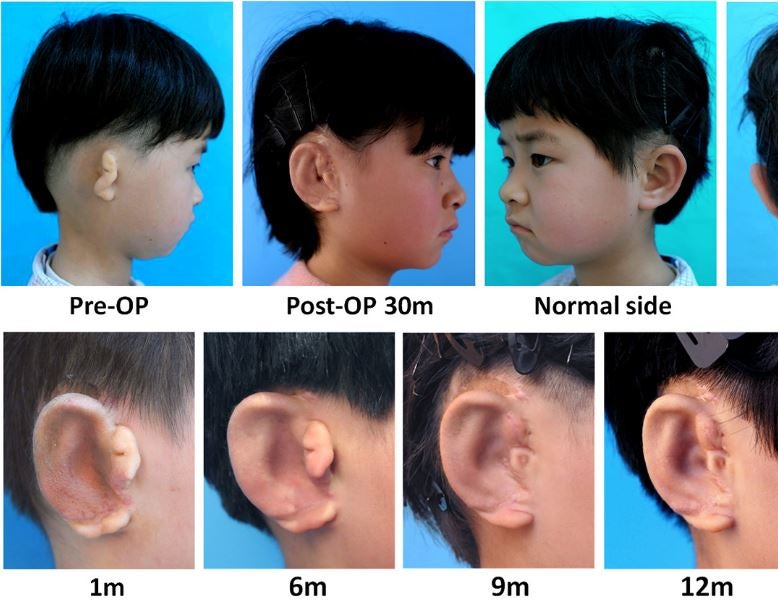

Scientists have grown a perfectly compatible ear in a lab and grafted it onto a patient, in what they said was a world first in regenerative medicine.

The groundbreaking technique saw them use the patient’s own ear cartilage cells to form a new one.

Five children suffering from a condition known as microtia, in which the external ear is underdeveloped, have undergone the experimental surgery.

The first child to have the procedure two-and-a-half years ago was showing no signs the body has rejected or accidentally absorbed the new cells, the Chinese team who developed the procedure wrote when they published their findings in the journal EBioMedicine.

Currently the widely used treatments for microtia include the use of silicone prosthetic ears, or rib-cartilage reconstruction, which has mixed results.

The new technique involves taking a scan of the child’s unaffected ear, reversing the dimensions and 3D-printing a biodegradable mould punctuated with tiny holes.

Cartilage cells taken from the recipient’s other, unaffected ear are then used to fill the holes while the new ear is still in the lab.

Over three months the cartilage cells begin to grow in the shape of the mould, and the mould itself begins to break down.

While this process is underway, the ear is grafted onto the recipient.

“It’s a very exciting approach,” Tessa Hadlock, a reconstructive plastic surgeon at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary in Boston, told New Scientist, which first reported on the research.

“They’ve shown that it is possible to get close to restoring the ear structure.”

The scientists will now monitor the recipients for at least five years to evaluate the success of the procedure. They will be checking whether the ears remain intact after the moulded scaffold has completely broken down, and working to refine the procedure in the hope of producing increasingly natural-looking ears.

The surgery was reportedly inspired by the so-called earmouse, a lab mouse which appeared to have a human ear growing on its back.

The 1997 experiment by a team in Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, led by Charles Vacanti, sparked an outcry among animal rights activists and religious groups after the publication of a picture of the live mouse.

Misinformation about the technique, including that the mouse had been “genetically engineered” to grow the ear sparked protests, despite the fact the ear had been grafted onto the mouse.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks