Breakthrough in spinal cord research could lead to eventual motor neurone disease cure

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have for the first time produced the "seed" cells of the human spinal cord in the lab – raising hopes that conditions such as muscular dystrophy could one day be treated by transplanting complex, lab-grown human tissue.

The spinal cord, a cylinder about the width of a little finger which runs down the backbone and is the core component of the central nervous system, is a hugely complex structure. Creating spinal cord tissue from stem cells has eluded researchers for years.

However, a major step has now been taken by Medical Research Council researchers at the University of Edinburgh, who set out to mimic the natural development of the spinal cord in the human embryo.

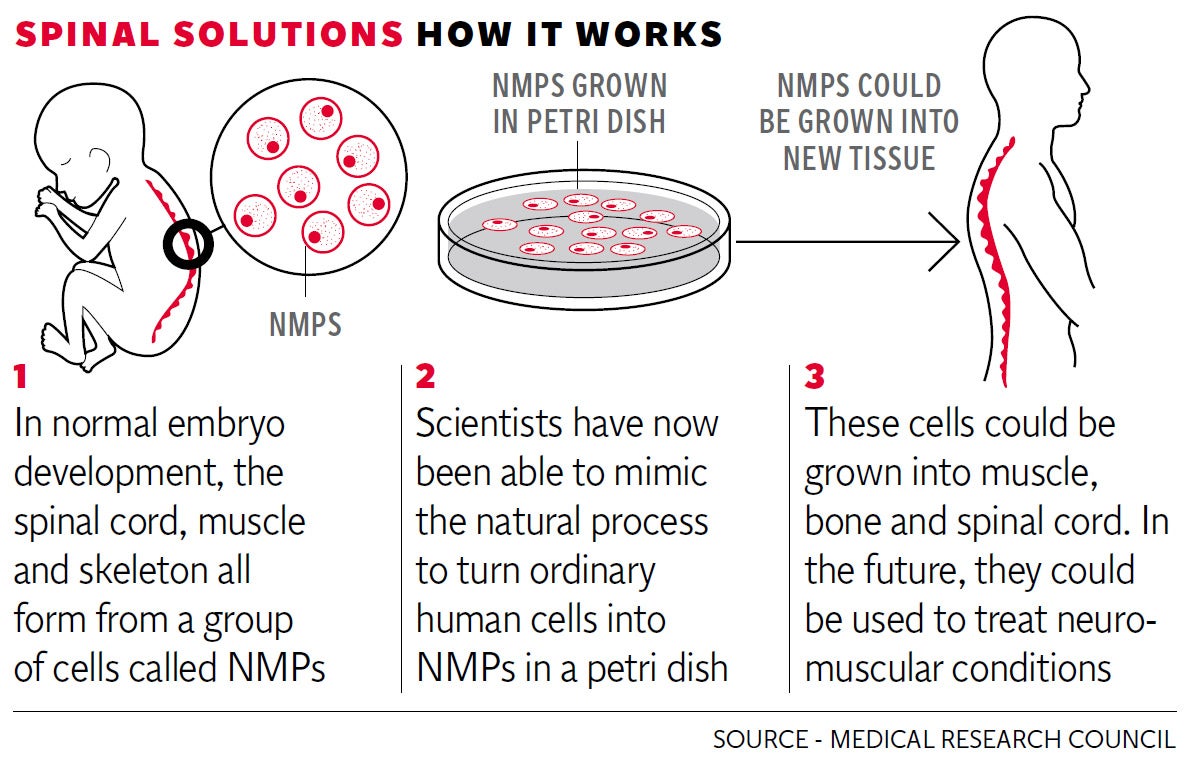

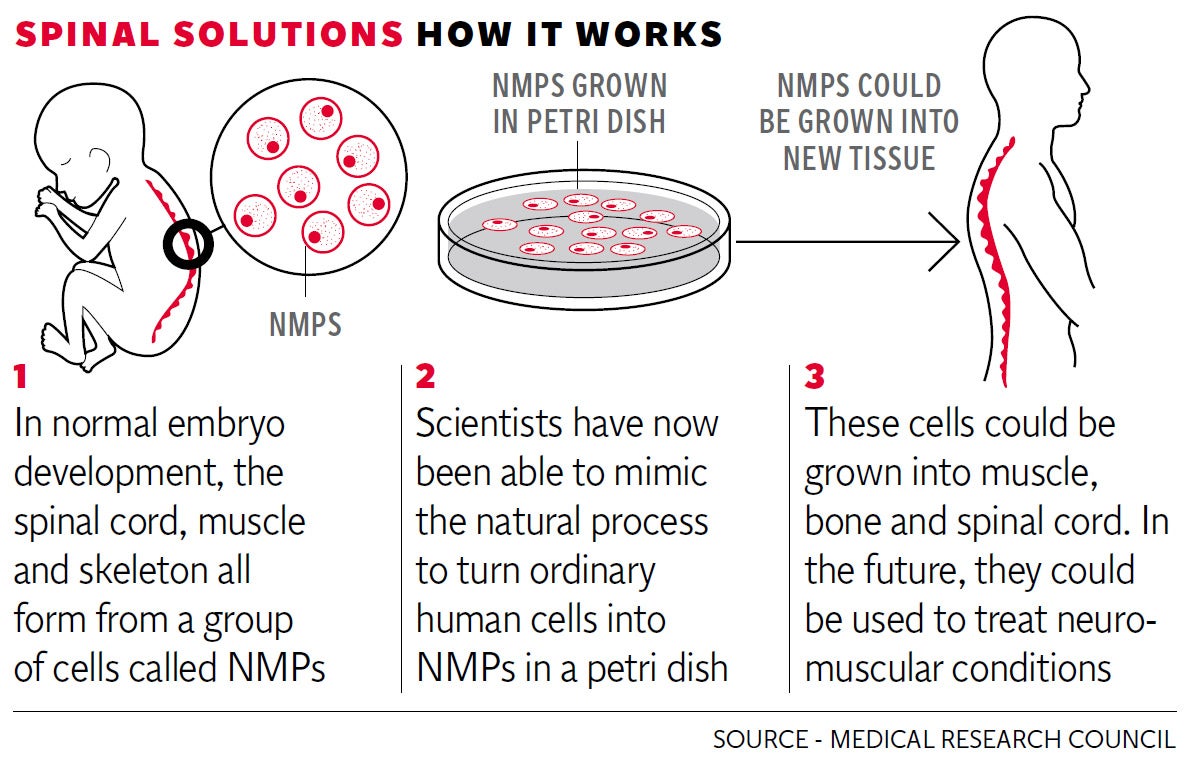

During normal embryo growth, the spinal cord, muscle and skeleton all form from a group of cells called neuro-mesodermal progenitors (NMPs). Experts realised that these "stepping stone" cells, which despite being known about for 100 years, had been overlooked by stem cell research, held the key to development of spinal cord stem cells.

By analysing and closely copying the complex series of chemical signals which take place in a growing embryo, they were able to make the ordinary stem cells of mice and of humans transform into NMPs, and then into spinal cord stem cells.

The team have not yet grown spinal cord tissue and the goal of using lab-grown spinal cord tissue to treat debilitating neuromuscular conditions such as muscular dystrophy and motor neurone disease is still many years away.

However, as well as paving the way for future advances, the breakthrough will enable scientists to study the development of these and similar diseases by taking stem cells from patients and watching whether they develop differently under the same process – potentially offering clues to the cellular cause of the disease.

“There have been some great advances in the field of stem cell research in recent years, with scientists being able to grow liver, heart and even some brain tissue in the lab. The spinal cord, however, has remained elusive because the NMP cells have largely been overlooked,” said Dr James Briscoe, who co-led the research at the MRC National Institute of Medical Research at Mill Hill.

“We can’t yet produce the tissues themselves, but this a really big step. It’s like being able to make the bricks and raw materials but not yet build the house,” he said.

“Understanding how nature normally does it gave us all of the clues we needed to artificially make these cell types from embryonic stem cells in petri dishes.”

Researchers have previously been able to grow some types of nerve, muscle and bone cells in the lab by converting them directly from stem cells. But this is the first time NMPs have been created from stem cells. Scientists hope that stem cells transformed through this natural development process will bear closer resemblance to those that occur naturally in the body – helping cells which might be used in transplants to better integrate with the body.

“NMPs are important because they’re the source of the spinal cord and most of the bones and muscles in our body,” said Prof Val Wilson, co-leader of the research. “But they have been like Cinderella cells. Although recognised for more than a century in the embryo, they’ve tended to be ignored by scientists trying to make these cell types in a dish. We hope this work will bring them out of obscurity and highlight their importance.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments