Brain abnormality may be to blame for anti-social teenagers

Aggressive teenagers with severe behavioural problems may have developed a biological abnormality in their brain, causing them to be aggressive and anti-social, a study has found.

Scientists believe they have discovered the first hard evidence showing that conduct disorder in adolescents has a biological basis connected with brain chemistry, rather than being the result of the desire in teenagers to ape their badly-behaved peers.

The findings suggest that it may be possible to diagnose a predisposition to conduct disorder in early childhood so that child psychologists could intervene before the behaviour starts to deteriorate. Conduct disorder affects five per cent of teenagers and costs society millions of pounds in terms of remedial education.

"Detecting conduct disorder in adolescence may be too late to do anything about it. Early identification of a biological abnormality may be a route to take in terms of early intervention," said Andy Calder of the Medical Research Council's Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit in Cambridge, where the study was carried out.

"These are pretty severe kids. They are frequently excluded from school over and over again. Some of them will go into young offenders institutions, so they are not just badly behaved kids," Dr Calder said. "Psychiatrists in the past have not really considered conduct disorder as a medical condition. This is research that's saying that actually it has a biological basis and this is soomething we should consider as a medical issue," he said.

The findings emerged from a study, published in the journal Archives of General Psychiatry, comparing the brain scans of 50 children with various degrees of conduct disorder with 23 ordinary children of the same age.

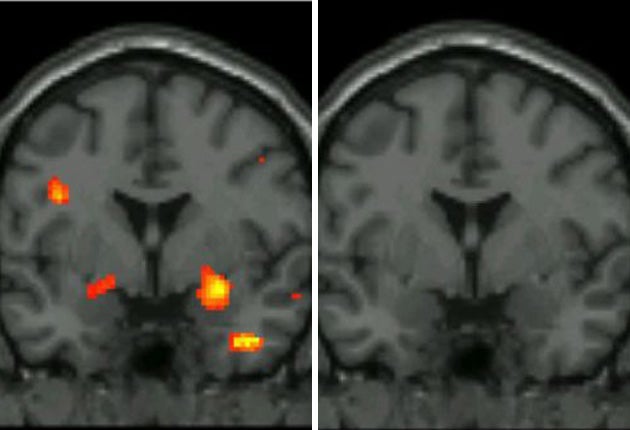

When the children were shown images of sad or angry faces, the brain scans of the ordinary children responded by showing high activity in parts of the brain linked with emotion.

However, the children with conduct disorder displayed a significantly poorer response to the images leading the scientists to suggest that this was because they were unable to empathise with another person's emotional state, making them more likely to commit anti-social acts. And the more severe a child's conduct disorder, the less activity was shown in scans, suggesting a possible cause and effect.

"We looked at who has the least and who has the most severe symptoms and we see an increasing pattern of abnormality as the symptoms in the individuals get worse. This does suggest a relationship between the severity of the symptoms and the abnormality in the brain response – it's certainly a significant relationship," Dr Calder said.

"At the moment we are not in a position to say that each child has conduct disorder based on the biology, but it's a direction the research should take," he said.

"It could be due to being born with a particular dysfunction or it could be due to experience during life, such as a distressing experience early in life that could have an impact on the way the brain responds," he added.

"We know it costs the Government 10 times as much to support a child with conduct disorder into adulthood, compared to a normal child. Research like this – which sheds light on the brain processes behind why and how these disorders emerge – is really important if we're to help sufferers and their families," he said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks