Beagle 2: Remembering Colin Pillinger – the man who sent the first British space probe to Mars

Eleven years after it disappeared, the space probe could have finally been found on Mars. It's a pity that its biggest champion isn’t here to find out what happened to it, says Steve Connor

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It started with a thunderous explosion of Soviet-era rocket engines, and ended somewhat disappointingly in mute nothingness. Now, after more than 11 years of radio silence, it seems that tomorrow we will finally be told what actually happened to Beagle 2, the first and only British space probe to land on Mars.

The UK Space Agency is widely expected to announce that Nasa's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been circling Mars and taking images of its surface for the past nine years, has detected the wreckage of Beagle 2. It that seems the probe ended up not far from its intended landing site, a large plain called Isidis Planitia, but incapable of sending back its call sign, a nine-note tune written by members of Blur.

On 2 June 2003, Beagle 2 and its mother ship the Mars Express were successfully lofted into space on board a Soyuz-Fregat rocket which enjoyed a perfect lift-off from the Baikonur launchpad in Kazakhstan. It was the start of a 250-million-mile journey to Mars that, for Beagle 2 at least, would end suddenly early on Christmas morning six months later.

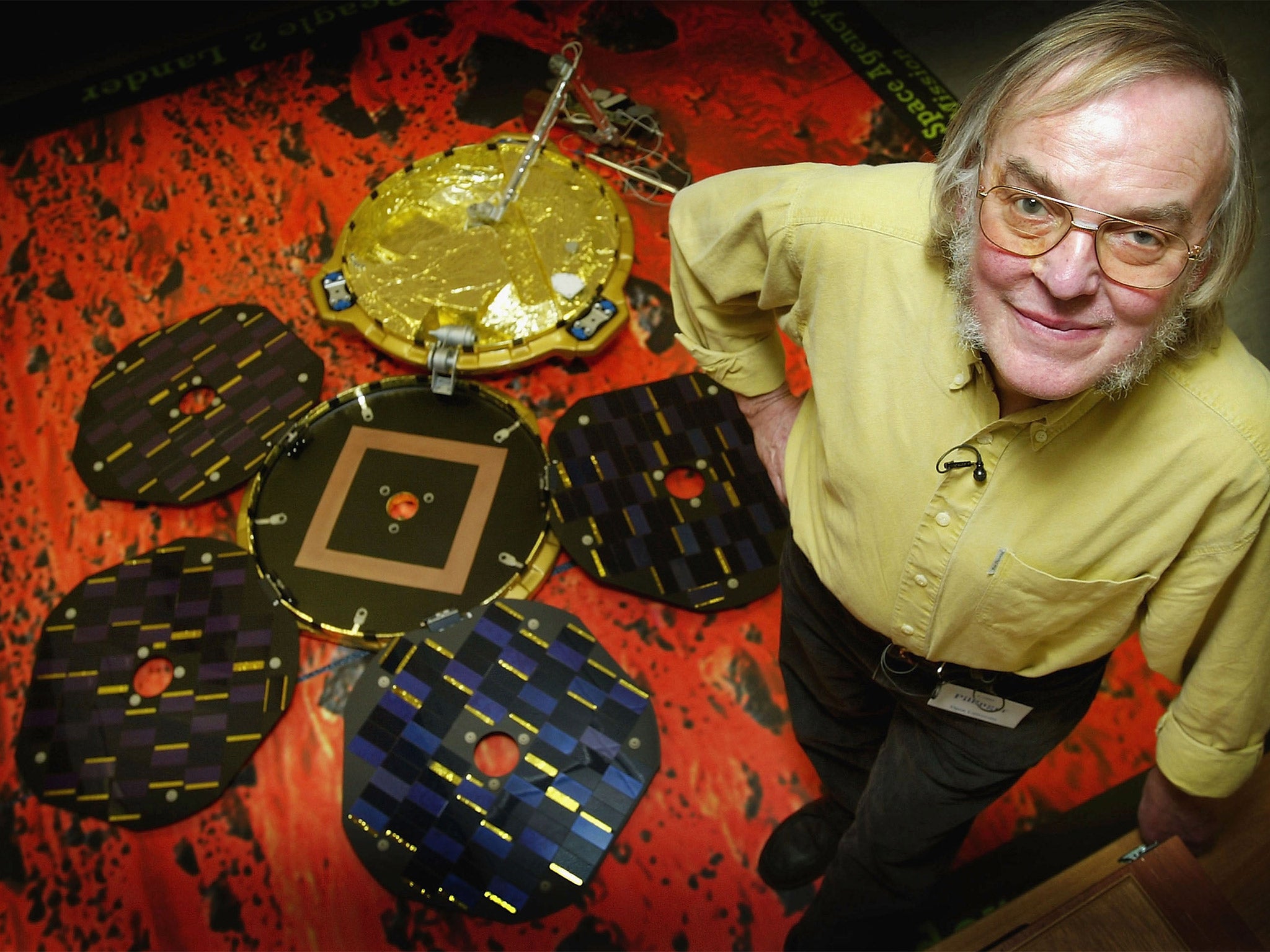

I remember that festive day well, trooping into a press conference bleary-eyed at 5am in the hope of hearing the call sign of Beagle 2 from its new home on the surface of the Red Planet. The room was a mixture of sleep-deprived exhaustion and emotional excitement, and no-one exemplified this better than the man who had nurtured the project from its inception, Professor Colin Pillinger, a planetary scientist at the Open University.

Colin was a natural enthusiast. Complete with mutton-chop whiskers, eccentric choice of clothes and his Bristolian burr, he was a science journalist's dream scientist. A few days before Christmas, Colin fielded questions from the press with the combined skill of a politician and stand-up comedian.

What happens if you find life, we asked? "I won't have any difficulty in getting money for the next mission," he quipped. How do you define life? The same as Charles Darwin, he shot back. "It must be capable to reproducing itself and evolving," he explained to the uninitiated.

As Beagle 2 successfully separated from the Mars Express spacecraft a few days before Christmas, Colin fell back on his favourite football analogies to express the battle ahead. The space mission is like a football match played in two legs, he said.

"And both of them were away, a long way away in space. We've travelled 250 million miles, we've got a one-nil result in the first leg. We're playing the second leg on Christmas Day," he told the science correspondents.

As it turned out, he was to lose the second match. The parachutes and set of three gas-filled bags were not enough it seems to protect the Beagle 2 from the trauma of descending through the thin Martian atmosphere to land safely and softly on the planet's surface.

"Ultimately, there's a point when you can say we have no idea where this spacecraft is," Colin said when it became apparent that Beagle 2 was not transmitting as it was expected in the early hours of Christmas Day.

"I'm afraid it's the usual England scenario – we're in extra-time," he added, ever hopeful that all was not yet lost.

Whatever the UK Space Agency reveals today, it has sadly come too late for Colin, who died last May without ever knowing what really happened to his baby. But if there is an afterlife, then one can imagine that somewhere up there a soul with a West-Country burr is having a quiet chuckle.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments