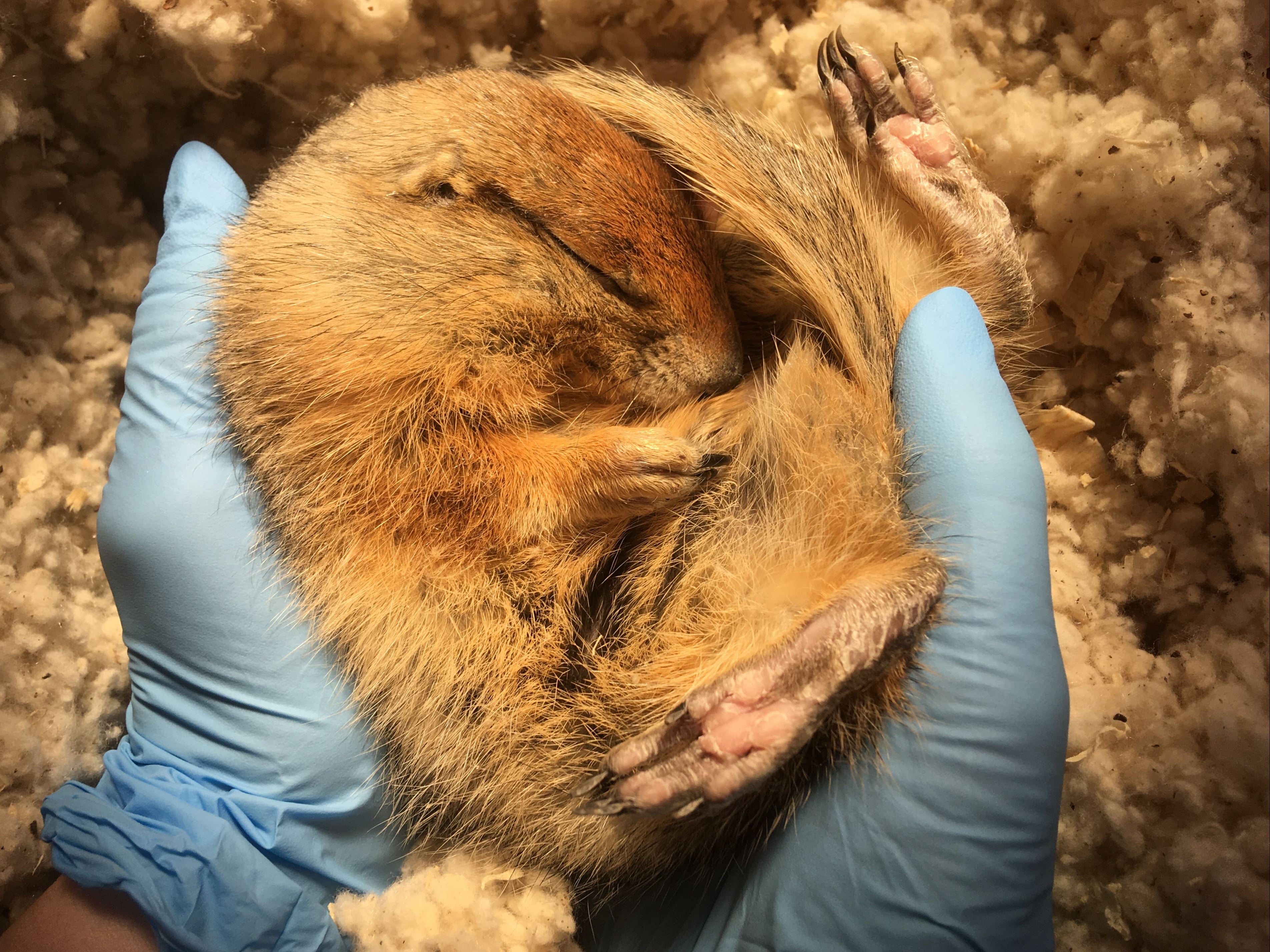

Hibernating Arctic ground squirrels ‘recycle body’s own nutrients’ to survive long cold winters

Breakdown of muscle during long stretch of inactivity releases nitrogen, which is used in other areas of the body, researchers find

Squirrels here in the UK don’t truly hibernate. They gather up their food, build nests and stay cosy over the winter in a snooze-fest during which they sustain themselves on the fruits of their labours, but it is not real hibernation.

However, some species of squirrel living in harsher environments do undergo full hibernation in order to make it through freezing winters, and what’s more, they have developed particular bodily functions to help them through this protracted period of dormancy.

A new study has found that Arctic ground squirrels are able to recycle their body’s own nutrients to survive while hibernating.

The University of Alaska Fairbanks-led study monitored ground squirrels in a laboratory environment for two years, measuring the almost undetectable flow of nutrients through their hibernating bodies.

As the ground squirrels’ muscles slowly broke down in temperatures just above freezing, researchers found that the animals were able to convert the free nitrogen this process was creating into amino acids.

Using those amino acids, the ground squirrels may then be able to create new proteins in tissues such as lungs and kidneys, and skeletal muscle, the research team said.

"They're just this extreme hibernator, and during the time they hibernate they don't eat, they don't drink, and they don't have any underlying injuries to their bodies," said Sarah Rice, a PhD student at UAF's Institute of Arctic Biology and lead author of the paper.

Researchers have been fascinated by the body chemistry of Arctic ground squirrels because of the rodents’ long and deep hibernation periods.

The discovery of how nitrogen is apparently recycled could unlock more of the “mysteries of hibernation, leading to new insights in human medicine”, the scientists said.

The squirrels’ bodies almost entirely shut down for as long as eight months a year, going without food and water while breathing just once per minute.

Despite that, hibernating ground squirrels are uniquely resilient to muscle loss and long-term cellular damage.

The findings complement previous research which suggested that hibernators recycle urea, a waste product that is excreted in urine.

Studies had indicated that those animals also recycle nitrogen to retain their body tissue during extreme fasting, but the new study is the first time that process has been confirmed in real-time on a metabolic scale.

Understanding the biochemistry of hibernation could contribute to a variety of potential medical treatments for humans, including the prevention of muscle loss in cancer patients and the elderly.

Harnessing the biological adaptations that are made during hibernation could also help treat traumatic injuries and aid astronauts during space travel, the researchers said.

By analysing how hibernators keep themselves healthy, the approach offers a different perspective from traditional therapies which often focus on overcoming and treating injuries, Ms Rice said.

“It's fun to kind of turn that idea on its head,” she said. “Instead of studying what goes wrong in the world, it's important to study what goes right.”

The study is published in the journal Nature Metabolism.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks