The ‘severed hand’ revealing how Stone Age Brits spoke to each other

So far paleolinguists have been able to determine the meaning of just one word - ‘fortune/luck’

New archaeological research may help reveal what language prehistoric Britons and some other western Europeans spoke long before any other languages were introduced.

Archaeologists in Spain have unearthed an ancient inscription which may give give an idea of what that prehistoric language may have been like.

The inscription – which appears to have been written in an early form of Western Europe’s oldest surviving language, Basque - opens up the possibility of working out the potential linguistic status not only of ancient Spain, but also of other parts of prehistoric Western Europe - including Britain and Ireland. That’s because genetic studies over the past decade suggest that southern and Atlantic Europe (including Spain and Britain) were colonised by the same wave of Middle-East-originating Neolithic migrants.

Archaeological evidence suggests that they entered Greece in around 6800 BC, reached Italy, Spain and western France by around 6000 BC, 5600 BC and 4800 BC respectively - and arrived in Britain and Ireland at some stage between 4300 and 4100 BC.

The ancient Basque-type inscription recently unearthed by archaeologists is the first ever discovered - and is important because some paleo-linguists believe that many of the Middle-East-originating migrants who colonised Mediterranean and Atlantic Europe in the early Neolithic are likely to have spoken Basque-related languages.

Paleo-linguistic evidence from elsewhere in Europe suggests that those languages and other Neolithic linguistic systems were not only introduced by the migrants into Spain, but probably also into Sardinia and France and possibly Sicily, the Italian peninsular and elsewhere.

Genetic evidence then shows that the same Middle-Eastern-originating Neolithic migratory movement which colonised southern Europe, then moved northwards along the Atlantic Coast and ultimately crossed the sea to Britain and Ireland.

It’s therefore likely that the early Neolithic peoples of Britain and Ireland spoke a language or languages related to some of those now also extinct languages spoken in early Neolithic southern Europe and Atlantic France.

The only surviving member of that early Neolithic group of languages is Basque. And the newly discovered inscription, unearthed in northern Spain, is the only known example of a text written in an ancient Basque-like language – probably an ancestral form of modern Basque.

The inscription consists of 40 letters without spaces (probably forming at least six words) Although it was written in around 100 BC (ie., during the late Iron Age), it may help paleo-linguists to begin to understand the relationship between early Basque and a now-long-extinct (potentially Basque-related) language in Spain called Iberian.

Unlike most surviving western European languages (except Basque and Sami [Lapp]), both Iberian and early Basque were non-Indo-European languages. An understanding of the relationship between Early Basque and Iberian may also eventually help to shed additional light on Western Europe’s other ancient (now extinct) pre-Indo-European languages such as Paleo-Sardinian, Paleo-Corsican, Aquitanian, (south-western France) and possibly Etruscan and Sicanian (central Sicily).

At present, all that is sometimes known of many of those languages are just a few surviving place and river names.

“Understanding the relationship between Basque and Iberian could be the key that enables us to begin to re-create the linguistic landscape of much of Neolithic Europe,” said one of Spain’s leading paleolinguists, Professor Joaquín Gorrochategui of the University of the Basque Country.

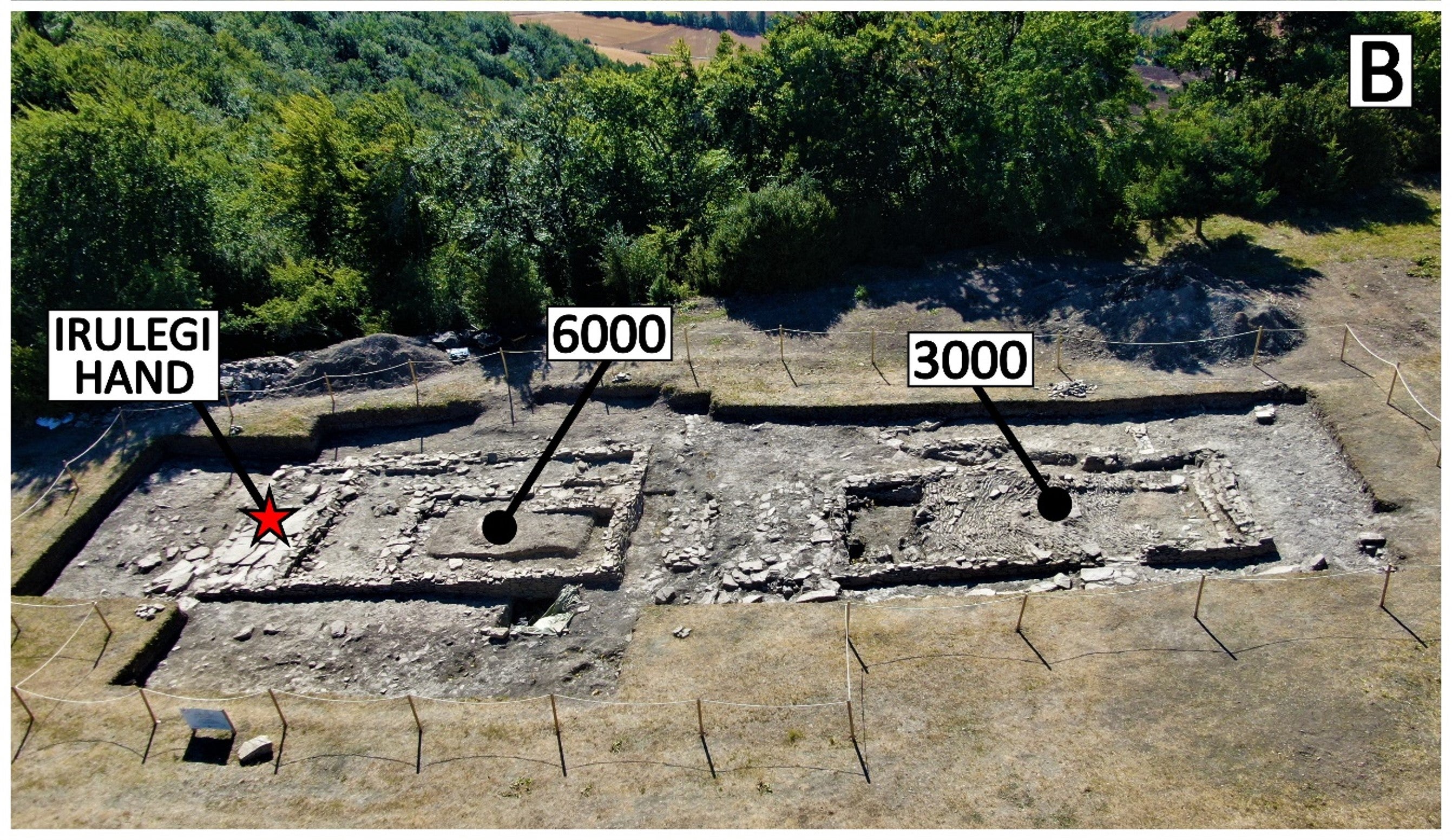

The inscription found in northern Spain was unearthed inside a major prehistoric settlement involved in a military conflict during the Roman occupation of Spain. Indeed, the inscription only survived because it was buried under a collapsed building destroyed during a Roman attack.

The inscription itself was inscribed on a symbolic sheet bronze hand. Like the still-used traditional hand symbols of the Middle East, North Africa and the Jewish world, it appears to have been some sort of good luck talisman. It seems to have been attached to the exterior of the front door of one of the houses in the Iron Age settlement.

So far, paleolinguists have been able to determine the approximate meaning of just one word - significantly ‘fortune/luck’.

The position of that specific word in the inscription suggests that it may well be the name of a deity of good fortune - like the Celtic God Sucellos, or the ancient Greek goddess, Tyche - or the Roman goddess, Fortuna.

But the symbol of the hand may also have been associated with a known regional Iron Age tradition of cutting off dead enemies’ hands and potentially using them as good luck or victory talismans.

The settlement was on a mountaintop (at an altitude of around a thousand metres) just five miles from the modern Basque city of Pamplona. It was heavily fortified, politicly important and probably had a population of around 500. Today the mountain’s name is Irulegi (Basque for ‘three cliffs’) - and indeed the ancient settlement at its summit would have been additionally protected by cliffs on three sides.

It is therefore conceivable that Irulegi (or a similar ancient version of that description) was the name of the settlement back in the Iron Age.

The Irulegi excavation was directed by Mattin Aiestaran of the Basque research organisation, the Aranzadi Science Society and The University of the Basque Country.

An academic paper on the bronze hand and its inscription is being published today Tuesday in the UK-based archaeology journal, Antiquity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments