Hoard of golden treasure stumbled upon by metal detectorist revealed to be most important Anglo-Saxon find in history

Archaeologists believe it was captured across several mid-seventh century battles

Britain’s most spectacular Anglo-Saxon treasures may well have been captured on a series of Dark Age battlefields – during bitter conflicts between rival English kingdoms.

Archaeologists, who have just completed a major study of the finds, now believe that they were captured in several big mid-seventh century battles.

It is likely that the treasures, now known as the Staffordshire Hoard, were seized (in perhaps between three and six substantial military encounters) by the English midlands kingdom of Mercia from the kingdoms of Northumbria, East Anglia and possibly Wessex.

The hoard – the greatest Anglo-Saxon golden treasure ever found – is one of the most important archaeological discoveries ever made in Britain.

After 10 years of detailed research, archaeologists are to publish a complete account of the hundreds of high status gold and silver objects found by a metal detectorist a decade ago in a field in southeast Staffordshire.

The book – published by the world’s oldest historical organisation, the Society of Antiquaries of London – describes all of the hoard’s 700 objects (4kg of gold items and 1.7kg of silver ones).

Strikingly, they do not seem to reflect the wide range of gold and silver artefacts which would have existed in Anglo-Saxon society.

Instead, the study demonstrates that the material is almost exclusively military in nature. Even one of the small number of ecclesiastical objects in the hoard appears to have been of a potentially military character.

The hoard was made up of golden fittings from up to 150 swords, gold and garnet elements of a very high status seax (fighting knife), a spectacular gilded silver helmet, an impressive 30cm-long golden cross, a beautiful gold and garnet pectoral cross, a probable bishop’s headdress – and parts of what is likely to have been a portable battlefield shrine or reliquary.

The extraordinarily ornate bishop’s headdress is the world’s earliest surviving example of high status ecclesiastical headgear.

Dating from the mid-seventh century AD, its presence in an otherwise predominantly military hoard suggests that its ecclesiastical owner may well have been performing a supporting role on a battlefield.

Significantly, the headdress bears no resemblance to later medieval or modern bishops’ mitres – and is therefore likely to trigger debate among historians as to its stylistic origins because it looks so similar in basic design to headdresses believed by early medieval clerics to have been worn by biblical Jewish high priests and also resembles headdresses worn by pagan Roman priests.

The discovery may therefore prompt scholarly speculation that the style of headwear worn by senior Christian priests in the early medieval period could have been at least partly inspired by perceived biblical precedent – or may even have been inherited from the pagan Roman past.

The headdress – made of beautifully crafted gold, inlaid with garnets and white and dark red glass – dates from the period when Christianity was being re-established across many of the local kingdoms that would eventually become England.

It represents the status and prestige of the Church – but, significantly, it is decorated with typical pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon semi-abstract animal designs as well as seven Christian crosses.

If indeed the archaeologists are right in believing it to be potentially an early-to-mid-seventh century bishop’s headdress, it would have been worn, perhaps during royal or other ceremonial events, by the first or second generation of clergy involved in the re-Christianisation of what is now England.

The portable shrine – potentially presided over by the owner of the headdress or a similar senior cleric – was probably designed to be carried into battle on two horizontal poles (like a litter or later sedan chair) – in order to obtain God’s help in securing military victory.

Only seven elements of the shrine, all made of gold, have survived.

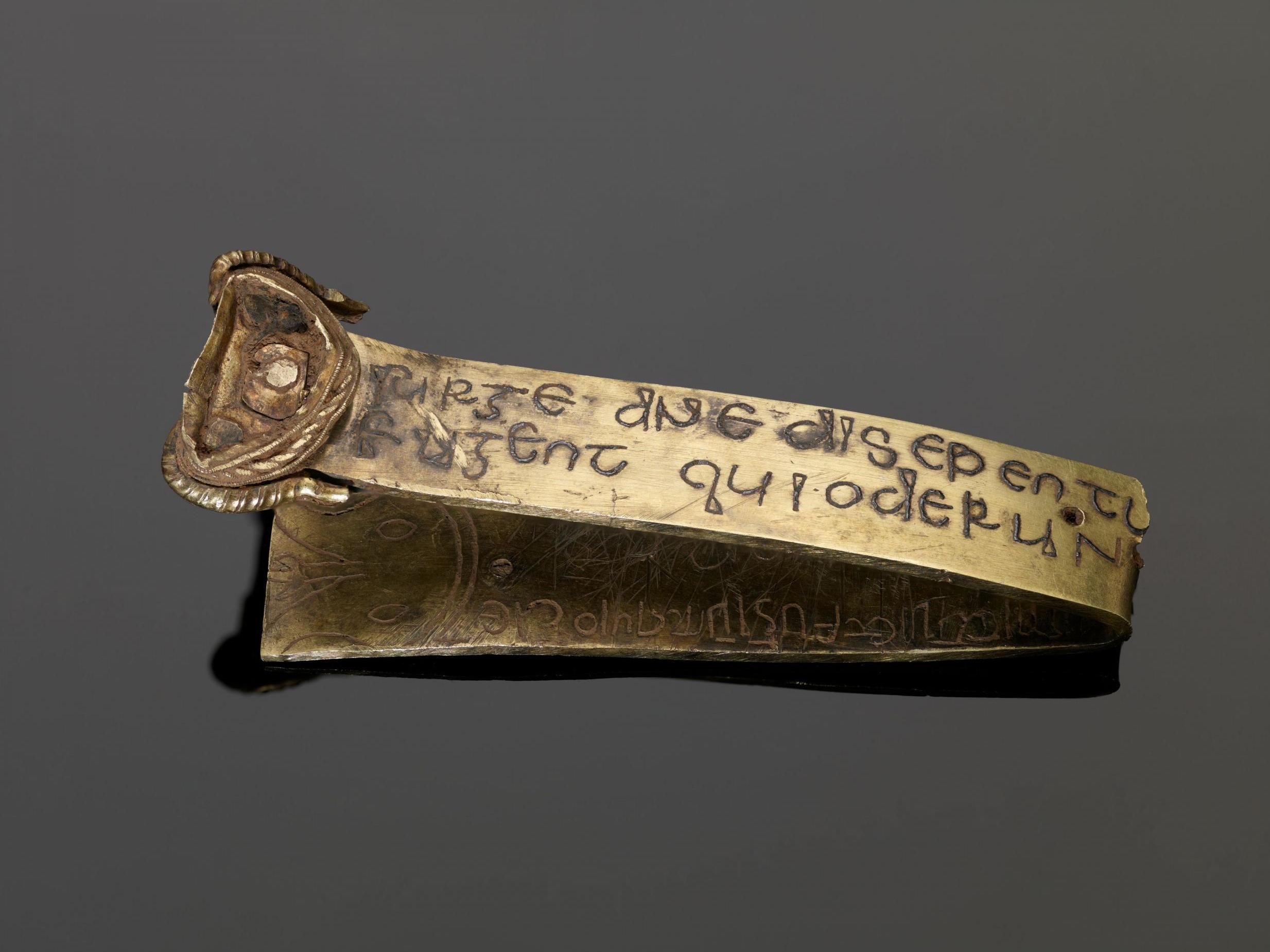

One element (probably part of a cross) bears a highly significant inscription – a quotation from the Book of Numbers. It reads “Rise up, LORD, and let thine enemies be scattered; and let them that hate thee flee before thee”.

Its biblical context is that of Moses uttering these words alongside the Ark of the Covenant accompanying the Israelites in their journey across the wilderness, threatened by hostile tribes. The nature of the inscription suggests that the precious shrine or reliquary (in Latin, arca) had probably been used as a war talisman in the long and bitter conflicts between warring kingdoms in early Anglo-Saxon England.

The ecclesiastical treasures and secular/military items appear to have been treated in a potentially disrespectful way before they were buried. They had been broken and/or folded and deliberately bent out of shape.

Back in the mid-seventh century, southeast Staffordshire (the area near Lichfield where the material was found) was controlled by a powerful pagan Anglo-Saxon king called Penda.

His geopolitical and military activity formed a major part of the bloodsoaked rivalry and conflict between his own kingdom (Mercia) and other, often Christian, kingdoms in other parts of England – especially in Northumbria and East Anglia.

Given the probable mid-seventh century date of the burial of the treasure, it is therefore possible that it was war booty captured by the pagan Mercian king, Penda, from armies led by Christians, such as the East Anglians.

One possible explanation is that the treasure was ritually buried as a Mercian pagan war trophy – perhaps even as a thanks offering to a pagan deity for delivering victory.

Putting Christian material into the ground in such a way may have been seen by Penda (or an equivalent figure) as a spiritual or ideological victory over Christianity to mirror a military one.

The 10-year investigation into the hoard has involved detailed scientific examination of the metalwork, exhaustive art historical assessment of the stylistic and iconographic aspects of the artefacts and research into the potential historical contexts of its burial.

However, now that the material has been fully published, there is likely to be an ongoing debate as to the most likely historical narrative or narratives that led to so much gold and silver being buried almost 1,400 years ago in a field in Staffordshire.

Scholars would love to know who originally owned the bishop’s headdress, the portable battlefield shrine and the golden helmet. But sadly the reality is that it may never be possible to definitively solve those particular mysteries.

However, there are potential candidates for the sort of individuals who may have been their original owners.

At around the time that the headdress was made, East Anglia was being Christianised, by the area’s first bishop a French cleric called Felix. It is therefore conceivable that the headdress was commissioned by him.

His successor as bishop was a man called Thomas, an East Anglian of possible Celtic British origin, and he would certainly be a candidate for the individual the Mercians actually captured the headdress from – because he died, potentially in battle, around the time that the East Anglian kingdom was defeated by Mercia.

The gilt silver helmet almost certainly belonged to an Anglo-Saxon royal figure.

“It potentially adorned the head of a king of East Anglia,” said one of the Staffordshire hoard book authors, archaeologist Chris Fern of the University of York.

“It is even more spectacular than the famous early seventh century helmet unearthed at the Anglo-Saxon royal burial site at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk, 80 years ago.

“Such helmets were the equivalents of royal crowns in Anglo-Saxon England,” said Mr Fern.

But perhaps one of the most fascinating questions raised by the Staffordshire Hoard is what inspired the strikingly unusual design of the probable bishop’s headdress. Was it biblical precedent – or ancient Roman priestly headgear? If the latter, it would suggest a potentially significant additional aspect of continuity between pagan Imperial Rome and early medieval Christianity.

One avenue of future research may well be linguistic rather than purely archaeological or historical.

Despite the fact that bishops are depicted bare-headed in Anglo-Saxon art, unpublished linguistic research by Anglo-Saxon clothing and textiles specialist Professor Gale Owen-Crocker suggests that early Anglo-Saxon bishops did indeed wear headgear known as a hufe.

Her research suggests that the Latin word for a bishop’s hufe was flammeolum or flammeum. Intriguingly, the pagan Roman priests, whose headgear may potentially have been the original inspiration for the type of bishop’s headdress in the Staffordshire Hoard, were known as the Flamines – and that suggests a potential and tantalising link.

The ecclesiastical material all appears to date from the second quarter of the seventh century – and to have been buried some time in the third quarter of that century.

The Christian and secular artefacts are being described in full for the first time in the newly-published book The Staffordshire Hoard: An Anglo-Saxon Treasure.

The treasure is on display at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery and The Potteries Museum and Art Gallery, Stoke on Trent. Although it is conceivable that it was interred for pagan ritual purposes, it is also possible that it was buried for safekeeping – and that its owners never returned to retrieve it.

The research into the Staffordshire Hoard has been funded by Historic England.

Its chief executive, Duncan Wilson, said: “The range of fascinating objects discovered has given us an extraordinary insight into Saxon craftsmanship and culture and this new monograph gives in-depth detail of everything we know about this spectacular discovery.”

To supplement the newly published book, the public can now access a new online information and picture database about the Staffordshire Hoard.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks