Skeletons of Scottish prisoners provide evidence of child soldiers in Britain's civil wars

Troops at the brutal Battle of Dunbar in 1650 may have been as young as 12

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Physical evidence that children were used as soldiers in Britain’s mid-17th century civil wars has been discovered by archaeologists.

Investigations in Durham have identified the remains of up to 28 skeletons as Scottish prisoners of war including a dozen teenage soldiers, five of whom were aged 12 to 16.

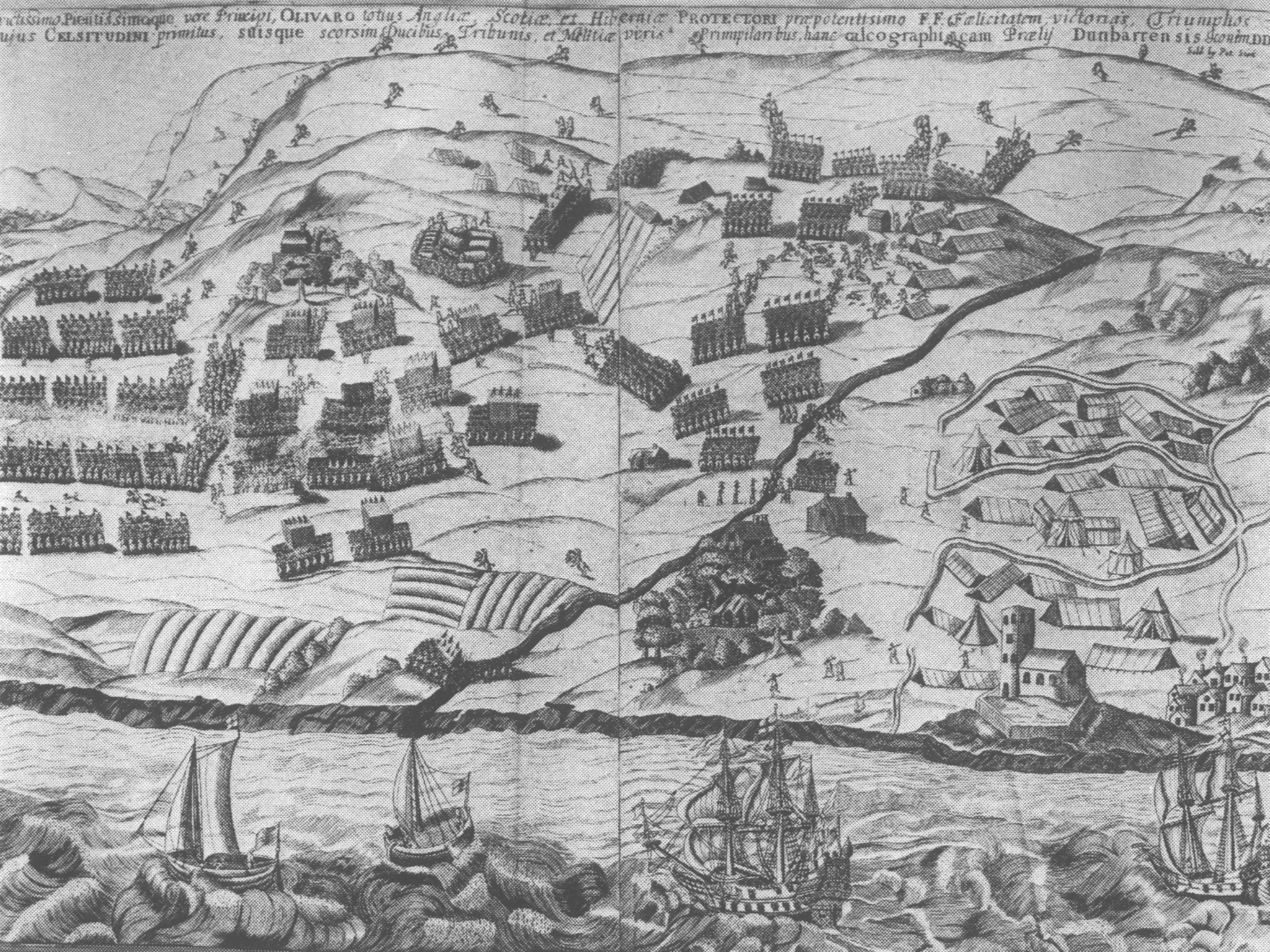

They were taken prisoner after English parliamentarian forces defeated the pro-Charles II Scottish Presbyterian army at the Battle of Dunbar on 3 September, 1650.

Scientific and other investigations carried out by the Durham University show that they almost certainly died of malnutrition, disease and dysentery.

One 13-15 year old boy who may have been suffering from scurvy had infections in his leg and foot bones.

A 14-15 year old appears to have been suffering from malnutrition for several years – and had had severe tooth decay and a leg infection.

A 12-16 year old had leg and foot infections – and probably also suffered from rickets.

The Battle of Dunbar was short and brutal. After less than an hour, a 12,000 strong English parliamentarian army, under the command of Oliver Cromwell, defeated the 11,000 strong Scottish covenanting army who supported the claims of Charles II to the Scottish throne.

Between 1,000 and 2,000 Scottish soldiers were killed by Cromwell’s forces who only lost 20 men.

The Scottish army had suffered from desertion, political purges and a severe lack of fighting age recruits. That almost certainly explains the presence of child soldier prisoners-of-war, unearthed in Durham.

Around 6,000 Scots were taken prisoners after the Battle of Dunbar. A thousand were immediately released because they were sick or wounded. The remainder were marched 100 miles south towards Durham where they were to be incarcerated in the castle and cathedral. Around a thousand died on the march - from hunger, exhaustion and dysentery. A few were executed. Some others escaped.

Around 3000 finally arrived in Durham, of who some 1700 then died of dysentery or disease at the rate of around 30 per day.

The identification of the Durham skeletons as Scottish prisoners taken at the Battle of Dunbar has involved detailed scientific and historical research – including isotopic tests showing that the individuals came from Scotland.

“Taking into account the range of detailed scientific evidence we have now, alongside historical evidence from the time, the identification of the bodies as the Scottish soldiers from the Battle of Dunbar is the only plausible explanation,” said Dr. Andrew Millard, Senior Lecturer at Durham University’s Department of Archaeology.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments