Unlucky ancient sea cow attacked by crocodile and then shark reveal secrets of prehistoric food chain

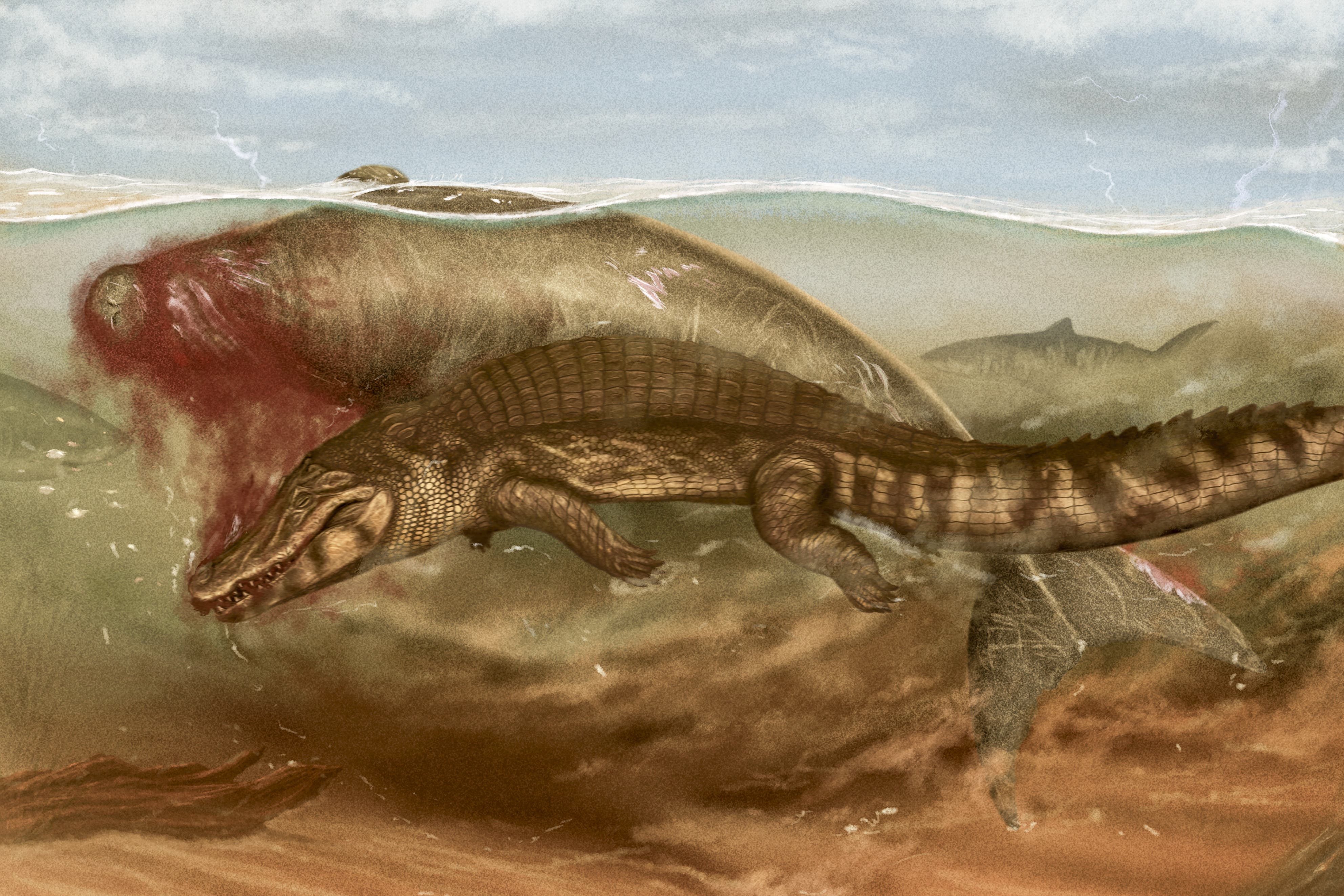

The sea cow died after the crocodile performed a death roll

The bones of an unlucky ancient sea cow has revealed more about the food chain during the Miocene epoch, around 23 million to 11.6 million years ago.

Skeleton analysis indicates the creature was first attacked by the prehistoric crocodile and then scavenged by a tiger shark, researchers said.

The sea cow, which belongs to the genus Culebratherium, died after the crocodile performed a “death roll” while grasping its prey, a behaviour commonly observed in modern counterparts.

The move involves delivering a powerful bite coupled with a full-bodied twisting motion, which allows the crocodile to disable, kill, and dismember prey.

The researchers said the findings, published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, marks one of the sole specimen examples of a creature being attacked by two different predators during the Miocene epoch.

Lead-author Aldo Benites-Palomino, from the department of paleontology at the University of Zurich, said their study highlights “the importance of sea cows within the food chain”.

He added: “While evidence of food chain interactions are not scarce in the fossil record, they are mostly represented by fragmentary fossils exhibiting marks of ambiguous significance.

“Our findings constitute one of the few records documenting multiple predators over a single prey, and as such provide a glimpse of food chain networks in this region during the Miocene.”

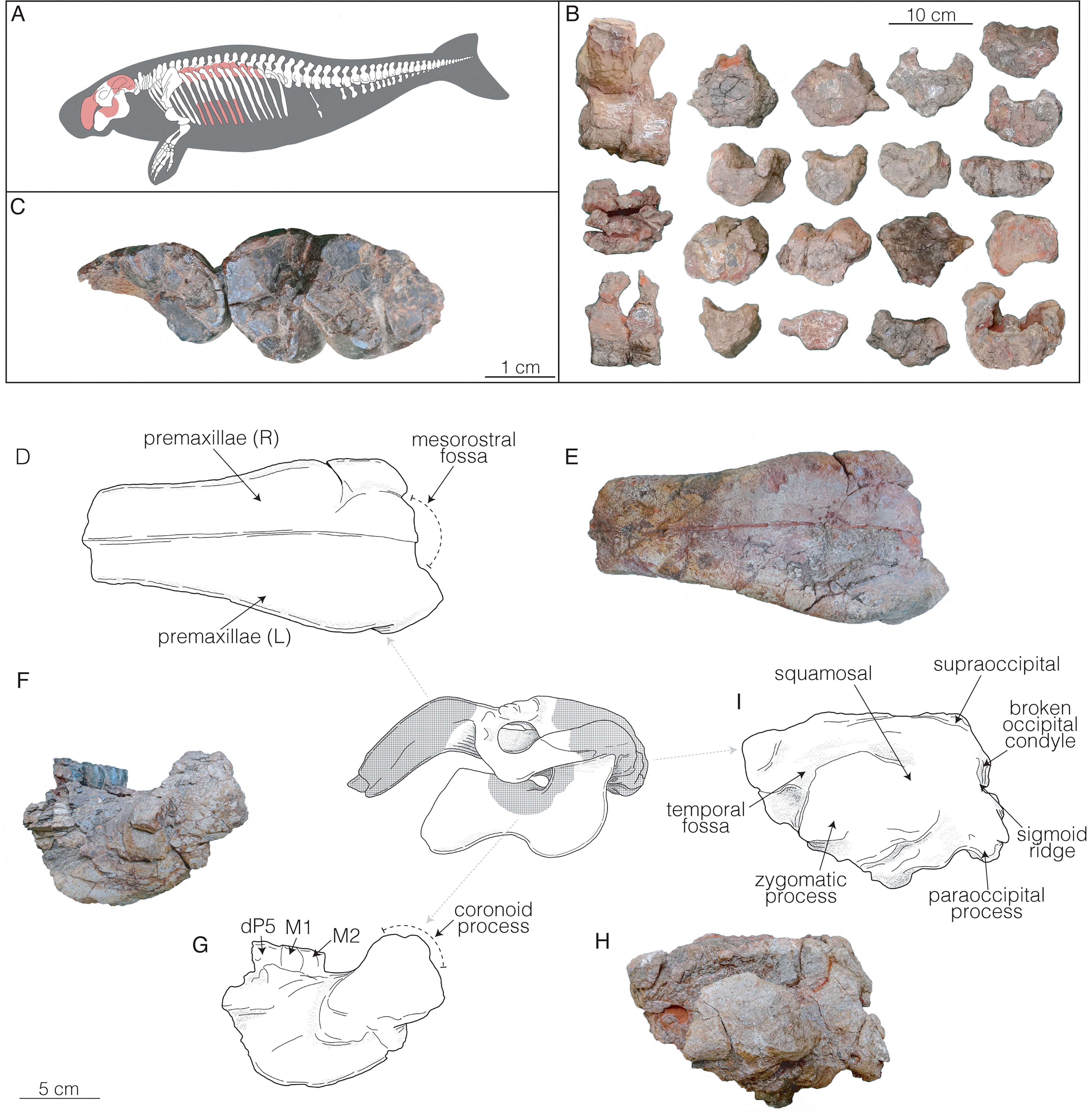

The researchers analysed skeleton remains, which included a partial skull and 18 associated vertebrae, unearthed near the city of Coro in Venezuela.

The team found what they describe as “conspicuous” deep tooth marks on the sea cow’s snout, suggesting the crocodile first tried to grasp its prey by the snout in an attempt to suffocate it.

Two further large incisions indicate the crocodile may have then dragged the sea cow, while striations and slashing marks across the fossil suggest it then executed a death roll, the researchers said.

A tooth of a tiger shark (Galeocerdo aduncus) was also found near the sea cow’s neck, along with shark bite marks observed throughout the skeleton.

This suggests the remains of the creature was then picked apart by this scavenger, the researchers said.

Marcelo R Sanchez-Villagra, director at the Palaeontological Institute & Museum at the University of Zurich, said the team first learnt about the fossil site, located in the outcrops of the Early to Middle Miocene Agua Clara Formation, through a local farmer who had noticed some unusual rocks.

He said: “Intrigued, we decided to investigate.

“Initially, we were unfamiliar with the site’s geology, and the first fossils we unearthed were parts of skulls.

“It took us some time to determine what they were – sea cow skulls, which are quite peculiar in appearance.

“By consulting geological maps and examining the sediments at the new locality, we were able to determine the age of the rocks in which the fossils were found.”

The researchers said several trips were required to excavate the skeleton, followed by months of preparation to restore and then study the fossil.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks