Nearly 400 hidden Roman forts uncovered from Cold War-era satellite images

Historians have for long debated strategic or political purpose of Roman-era forts in the region

Archaeologists have uncovered nearly 400 previously unknown Roman forts built about 1,900 years ago and buried across modern-day Iraq and Syria by re-examining Cold war-era satellite images.

The research published in the journal Antiquity sheds more light on forts in Rome’s east that were thought to serve as a line of defence against incursions from the ancient civilisation’s eastern frontiers.

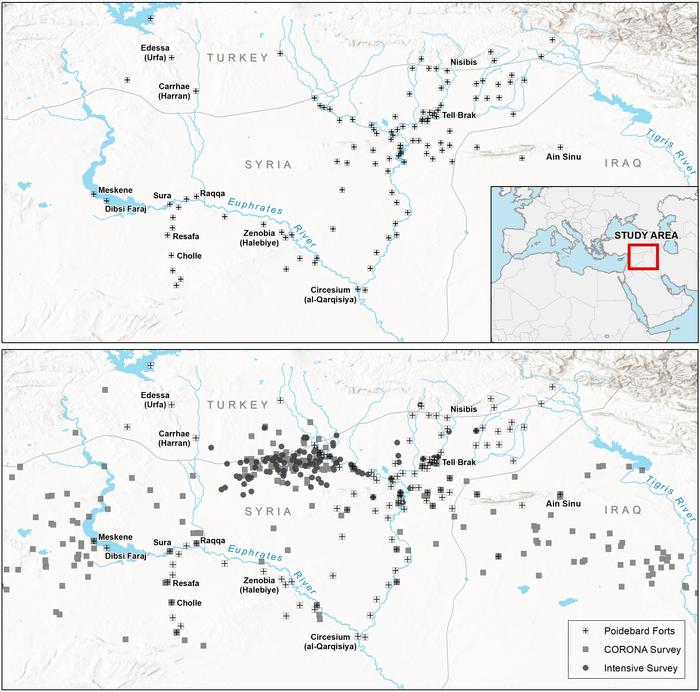

During an aerial survey of the Near East in the 1920s, French Jesuit priest Antoine Poidebard, a pioneer in aerial archaeology, recorded hundreds of fortified military buildings in the region.

Father Poidebard proposed that these forts likely represented a line of defence for the Roman Empire against incursions from the east.

In his survey, he mapped 116 Roman forts along a 1,000km (620 miles) border, and argued that these buildings were been built during the second and third centuries AD to defend against Arab and Persian invaders.

However, historians and archaeologists have for long debated the strategic or political purpose of this system of fortifications.

Now, the latest research, assessed declassified images from the world’s first spy satellite programmes – Corona and Hexagon collected between 1960 and 1986.

Rectification and reanalysis of these old images has helped identify previously undiscovered 396 more forts widely distributed across the northern Fertile Crescent.

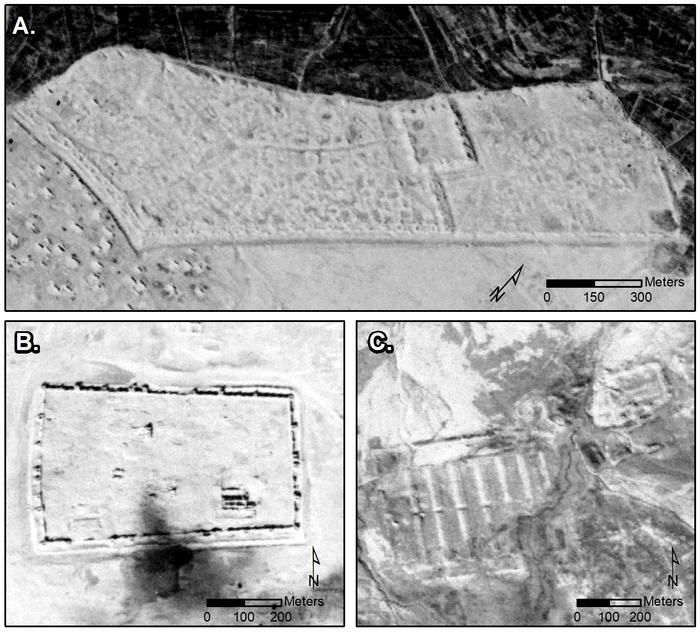

Researchers from Dartmouth College in the US could distinguish these forts from modern buildings and identify their archaeological features due to their due to the distinctive shadows and eroded walls.

“These buildings are often isolated, far from other obvious archaeological features, and frequently located in marginal environments with little other evidence of ancient or modern settlement,” scientists explained.

The forts, according to researchers, connect Mosul on the Tigris River in the east with Aleppo in western Syria.

Contrary to Father Poidebard’s interpretation of his discovery, the latest analysis suggests the forts are spread over an enormous, east-west trending region.

This suggests that these forts supported the movement of “troops, supplies or trade goods” between the east and west, scientists say.

They say the region was more likely a hub of global trade than as a defensive line against invaders from the east.

“The addition of these forts questions Poidebard’s defensive frontier thesis and suggests instead that the structures played a role in facilitating the movement of people and goods across the Syrian steppe,” archaeologists write in the study.

“Instead, our findings strengthen an alternative hypothesis that such forts supported a system of caravan-based interregional trade, communication and military transport,” they added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks