Half-a-billion-year-old new species reveals the origins of the octopus

Researchers discovered a new species of mollusc that lived 500 million years ago

A half-a-billion-year-old spiny slug had shed light on the origins of animals like oysters and octopuses, researchers have said.

Researchers including scientists from the University of Oxford have discovered a new species of mollusc that lived 500 million years ago.

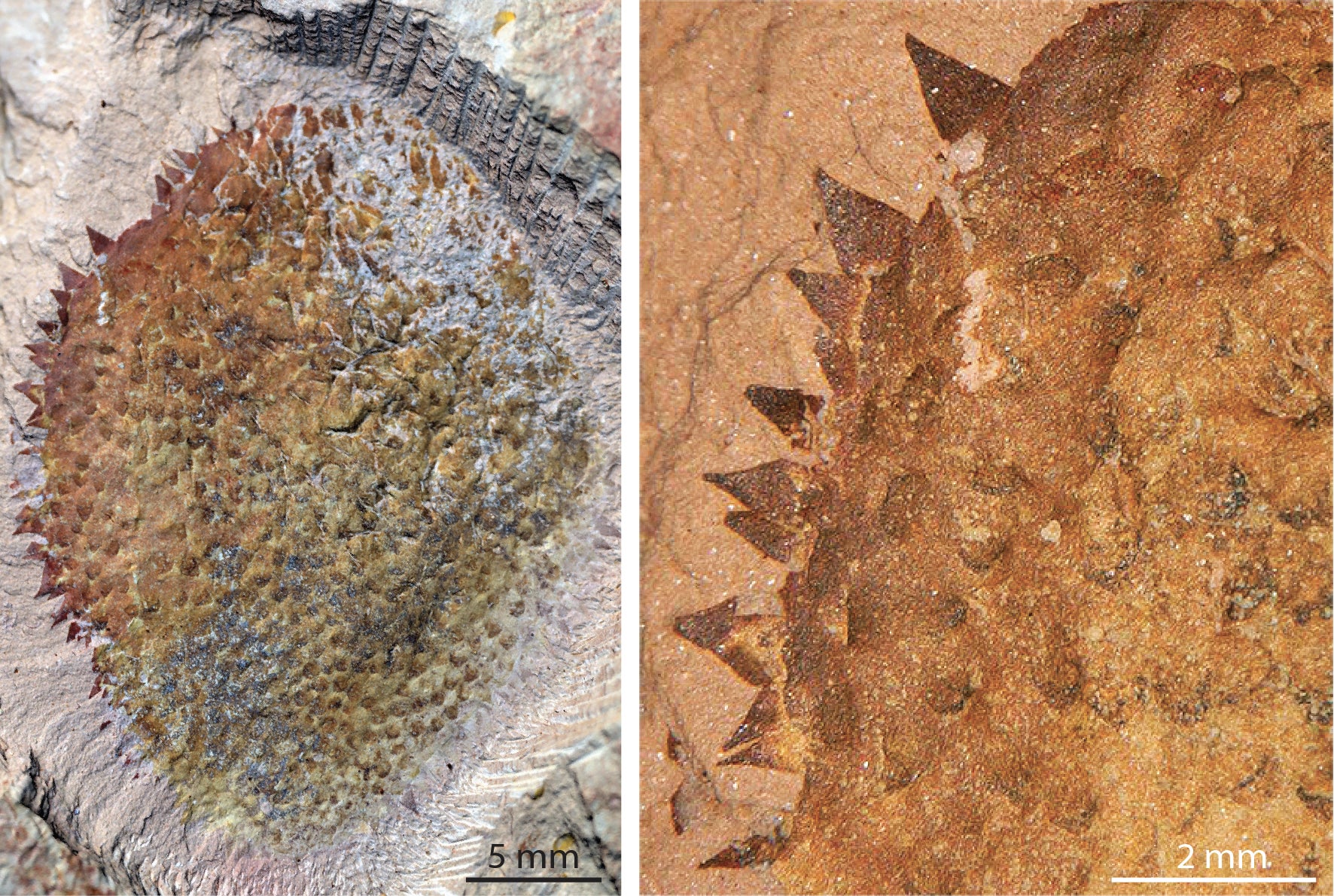

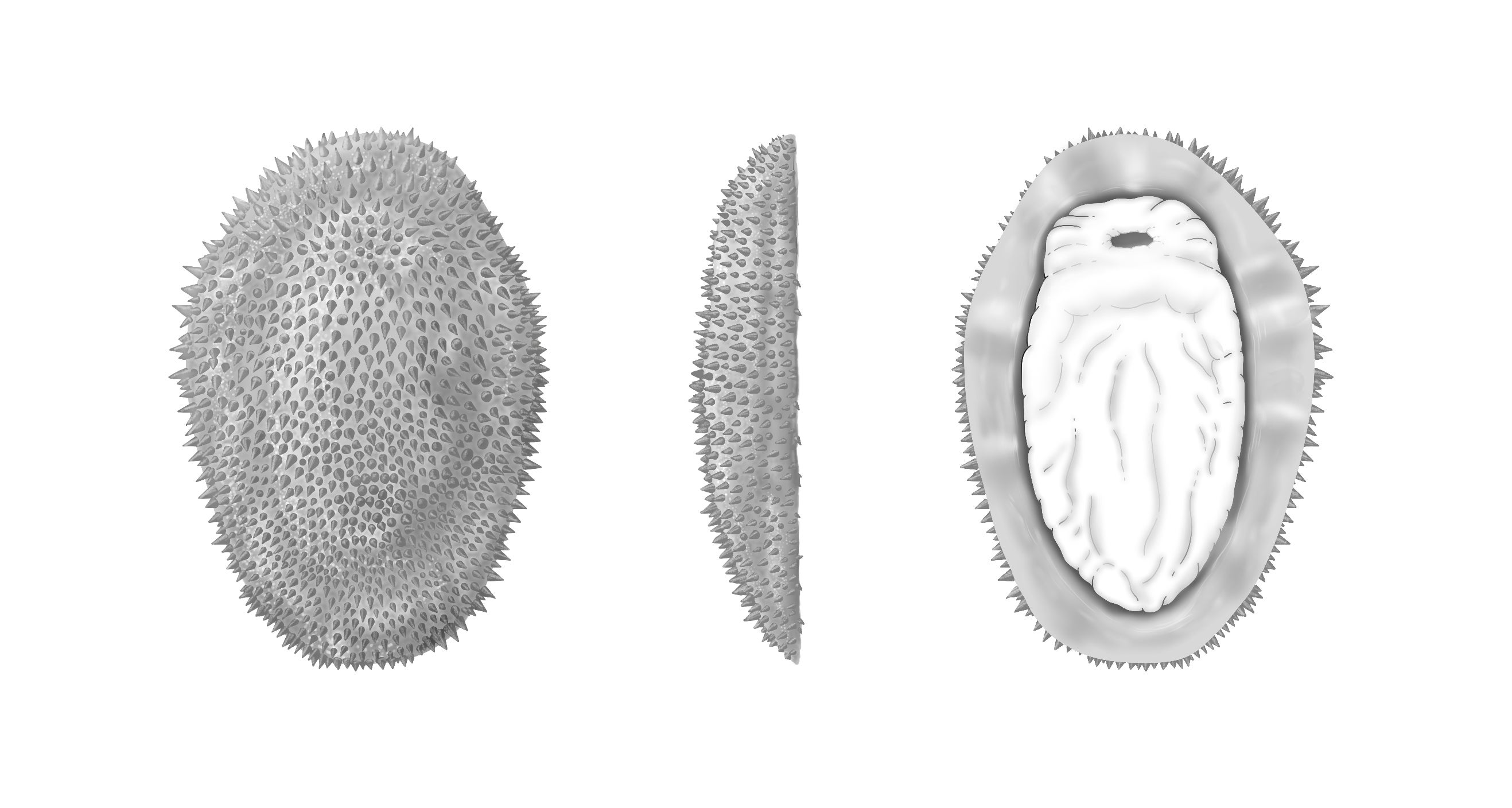

Called Shishania aculeata, the new fossil reveals that the earliest molluscs (animals that do not have a backbone) were flat, shell-less slugs covered in a protective spiny armour.

Some of the fossils were preserved upside down and show that the bottom of the animal was naked, with a muscular foot like that of a slug.

Experts suggest Shishania – initially referred to as “the plastic bag” because of its appearance – would have used this food to creep across the seafloor.

Corresponding author associate professor Luke Parry of the department of earth sciences at Oxford said: “Trying to unravel what the common ancestor of animals as different as a squid and oyster looked like is a major challenge for evolutionary biologists and palaeontologists – one that can’t be solved by studying only species alive today.

“Shishania gives us a unique view into a time in mollusc evolution for which we have very few fossils, informing us that the very earliest mollusc ancestors were armoured spiny slugs, prior to the evolution of the shells that we see in modern snails and clams.”

The new species was found in well-preserved fossils from eastern Yunnan Province in southern China dating from a geological period called the early Cambrian, approximately 514 million years ago.

The specimens of Shishania are all only a few centimetres long and are covered in small spikey cones made out of a material (chitin) also found in the shells of modern crabs, insects, and some mushrooms.

Unlike most molluscs, Shishania did not have a shell that covered its body, suggesting that it represents a very early stage in the evolution of the animal.

Today molluscs come in many different forms, including snails and clams and even highly intelligent groups such as squids and octopuses.

This diversity evolved very quickly a long time ago, and because of this, very few fossils have been left behind that chronicle the early evolution of molluscs.

First author Guangxu Zhang, a recent PhD graduate from Yunnan University in China who discovered the specimens, said: “At first I thought that the fossils, which were only about the size of my thumb, were not noticeable, but I saw under a magnifying glass that they seemed strange, spiny, and completely different from any other fossils that I had seen.

“I called it ‘the plastic bag’ initially because it looks like a rotting little plastic bag. When I found more of these fossils and analysed them in the lab I realised that it was a mollusc.”

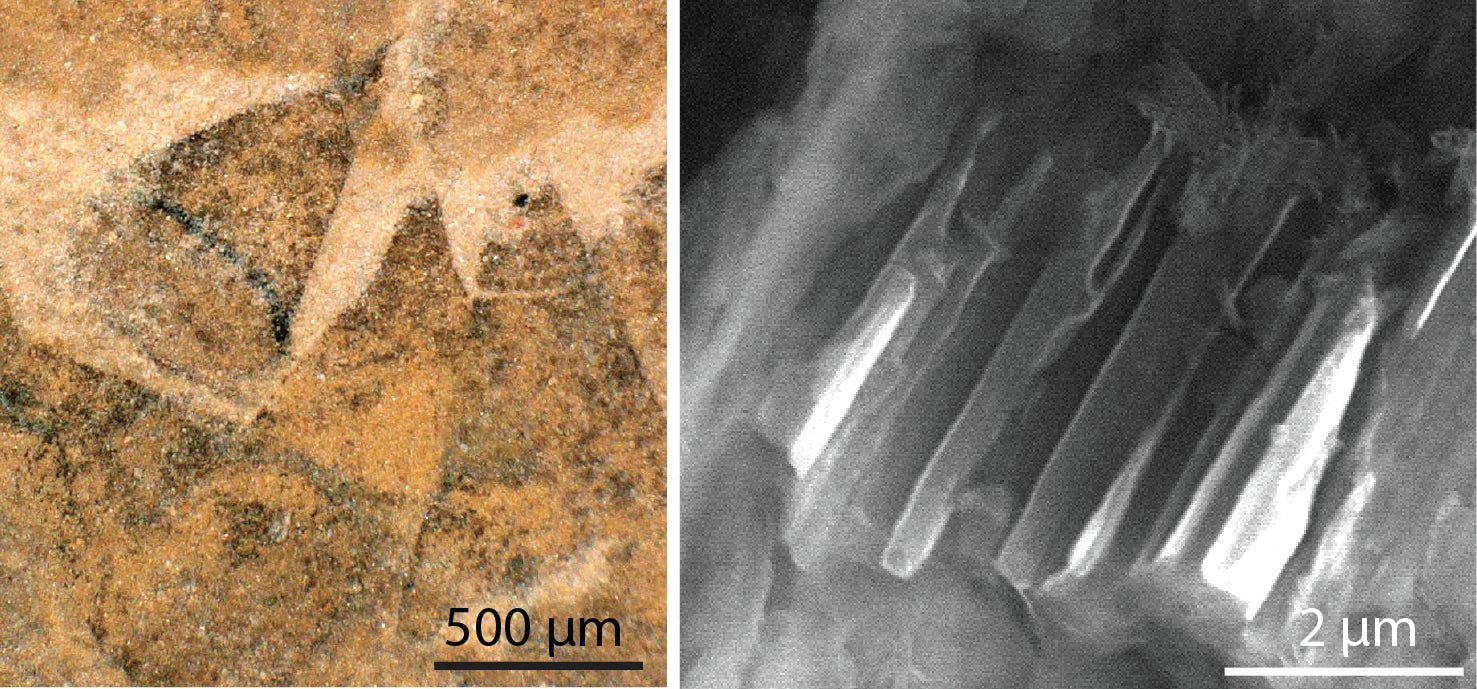

The spines of Shishania show an internal system of canals that are less than a hundredth of a millimetre in diameter.

These features show that the cones were secreted at their base by tiny protrusions of cells that increase surface area, such as in our intestines where they aid food absorption.

Researchers say this method of secreting hard parts would be like the workings of a natural 3D printer.

This allows any invertebrate animals to secrete hard parts with huge variation of shape and function, from providing defence to facilitating movement.

Co-author Jakob Vinther at the University of Bristol said: “We know that the common ancestor of all molluscs alive today would have had a single shell, and so Shishania tells us about a very early time in mollusc evolution before the evolution of a shell.”

The findings are published in the journal Science.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks