This ancient giant tadpole will change what we know about frogs

Scientists have found the oldest-known fossil of a tadpole that wriggled 160 million years ago

Scientists have discovered the oldest-known fossil of a giant tadpole that wriggled around over 160 million years ago.

The new fossil, found in Argentina, surpasses the previous ancient record holder by about 20 million years.

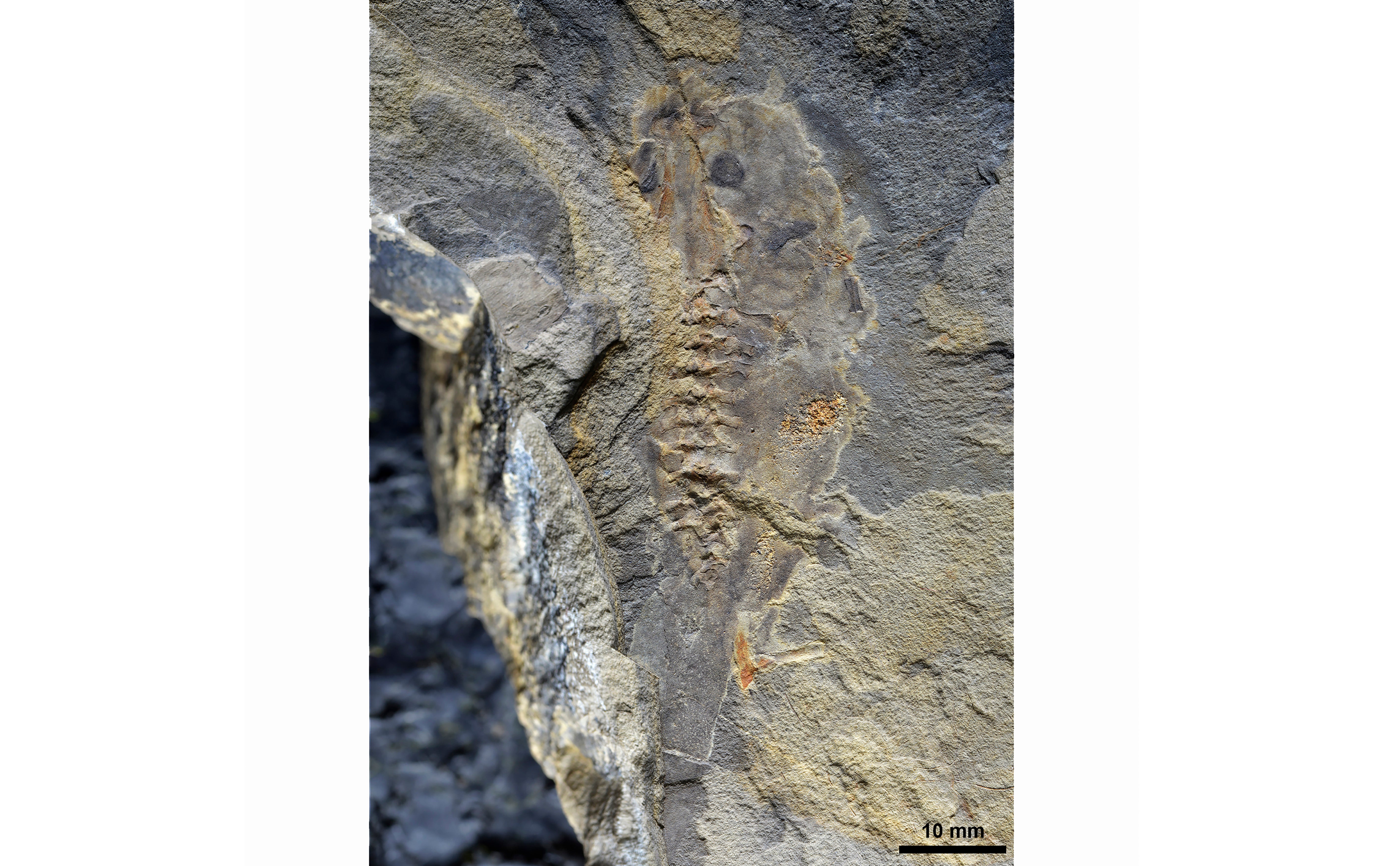

Imprinted in a slab of sandstone are parts of the tadpole's skull and backbone, along with impressions of its eyes and nerves.

“It's not only the oldest tadpole known, but also the most exquisitely preserved,” said study author Mariana Chuliver, a biologist at Buenos Aires’ Maimonides University.

Researchers know frogs were hopping around as far back as 217 million years ago. But exactly how and when they evolved to begin as tadpoles remains unclear.

This new discovery adds some clarity to that timeline. At about a half foot (16 centimeters) long, the tadpole is a younger version of an extinct giant frog.

“It's starting to help narrow the timeframe in which a frog becomes a frog,” said Ben Kligman, a paleontologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History who was not involved with the research.

The results were published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

The fossil is strikingly similar to the tadpoles of today — even containing remnants of a gill scaffold system that modern-day tadpoles use to sift food particles from water.

That means the amphibians' survival strategy has stayed tried and true for millions of years, helping them outlast several mass extinctions, Kligman said.

John Long, a palaeontologist at Flinders University told abc.net.au:“Frogs metamorphose from tadpoles … that’s one of the most dramatic transformations in the life history of any backboned animal on the planet,” Professor Long said.

Adding: “It’s like a Mona Lisa. It’s a masterpiece of evolution’s artistry”.