Global Seed Vault: the Arctic’s doomsday depository that could save plant life from climate change

Tucked away inside a mountain in the Arctic lies humanity's chance for salvation from environmental catastrophe

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Some 1,300 miles into the Arctic Circle and just 650 miles from the North Pole lies the world’s most important freezer.

Situated on Spitsbergen Island in the Svalbard archipelago, the Global Seed Vault is owned by the Norwegian government and sits next to the world’s northernmost town, Longyearbyen, with a population of just over 2,000.

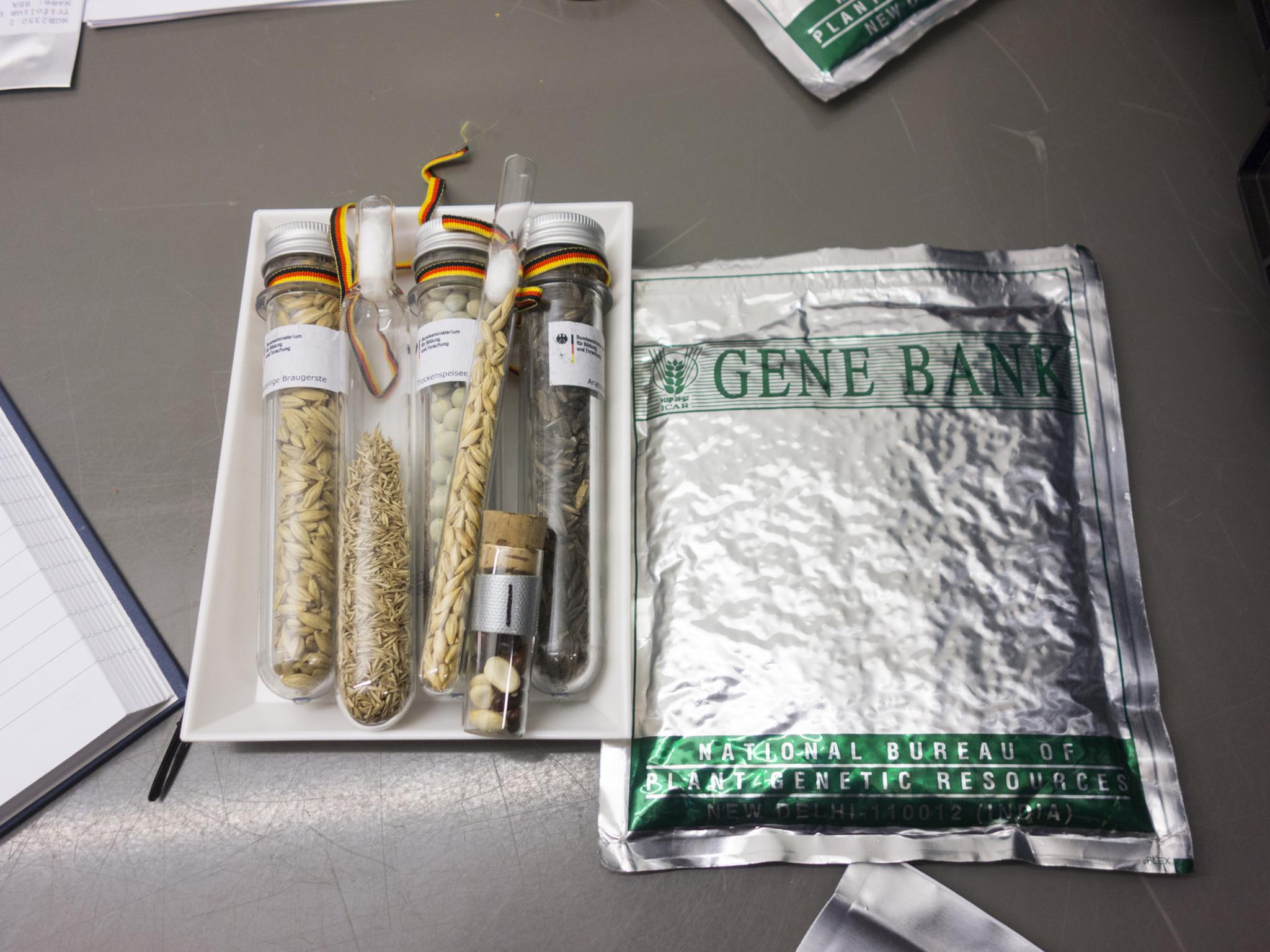

Contained within in it are 930,000 varieties of the world’s most precious seeds, sent by the gene banks across the globe to insure them against risks in their home country, such as natural disasters, war and looting.

Built to house as many as five million seed varieties, in the most extreme circumstances, the vault is intended to act as a “doomsday” depository for global agriculture, should a major catastrophe wipe out the plants we rely on. But it’s main role is in protecting diversity from threats that already exist today.

“Today climate change is challenging agricultural production,” says Marie Haga, a former leader of Norway’s Centre Party and the executive director of the Crop Trust, which advises on and part-funds the vault.

“Plants have always adapted. Wheat originates in the Middle East and now we grow it all over the world, but it has taken thousands of years for wheat to move from the Middle East to somewhere like Canada. The basic problem today is that climate change is happening faster than plants are able to adapt.”

“The primary aim of the vault is to make sure that mankind has access to a maximum diversity of crops to be able to adapt to new challenges in the future.”

According to Kew’s State of the World’s Plants report, there are currently 390,000 plant species known to science, with around 30,000 used by people. Their report estimated that one in five plants are at risk from extinction, with habitat loss the leading cause of extinction risk.

“We are losing genetic diversity rapidly, both in the field and in gene banks around the world,” says Marie. “For each variety of seeds that we lose, we also lose options for the future.”

Three vaults lie at the end of a 130m tunnel inside the flank of Mount Plateau, allowing the seeds to be stored deep within the Arctic permafrost. In the Vault Room the seeds are cooled to an optimal –18C.

Three times a year this unique facility opens up its doors to allow countries to make deposits in the frozen vaults. Flown in by air to the world’s northernmost airport, any collaborating gene bank has to send over at least 500 examples of a given crop variety and remain proprietors of their seeds, should they ever need them.

To the surprise of many, the bank has already been used for its intended purpose. After the International Gene Bank of Syria determined their Aleppo site was too hard to administer in 2015, the site’s administrators requested their boxes from the vault in order to replenish new research facilities in Lebanon and Morocco.

It may seem like a rarefied endeavour but there are 1,700 gene banks dotted across the world, and many are considered to be at risk as a result of lack of funding, poor infrastructure, not enough or qualified technical human resources, or information systems.

In Afghanistan, two of the country’s seed banks have been looted, not for the seeds, but for the plastic containers used to store them. Hurricane Xangsane wiped out another bank in the Philippines.

“We have also lost seed collections in Iraq due to the war,” says the Crop Trust’s Marie Haga. “In China today they only use 10 per cent of the rice varieties they would have used back in 1950. In the US they have lost more than 90 per cent of their fruit and vegetable varieties in the field. So it’s very important that this material exists in gene banks, and it’s awfully important that we have backup systems”.

Locating the seed bank deep inside a mountain in the Arctic Circle is both an important security feature of Svalbard, and a failsafe if the cooling system no longer works. If the power supply is cut off or the refrigeration units fail, the inside of the mountain would maintain a steady temperature of –5 to –8C.

Although not all the seeds would be saved, a feasibility study suggested many of the deposits would last for hundreds if not thousands of years without human intervention.

Mount Plateau is also geologically stable with limited humidity and with low radiation readings inside the mountain itself.

The Norwegian government, which owns the vault, says it has a “virtually infinite lifetime” and is “robustly secured against external hazards and climate change effects”.

It certainly seemed to be the perfect site for this endeavour.

However, the government had not anticipated what has proven to be the hottest year on record, resulting in extreme weather conditions in the Arctic.

Despite having been positioned in an area where ice is supposed to remain frozen all year round, in May this year the permafrost melted, breached the bank’s entry doors and caused water to enter the facility’s 130m long entrance tunnel.

Fortunately none of the seeds were affected by the meltwater as it refroze before it could reach the vault.

“It was not in our plans to think that the permafrost would not be there and that it would experience extreme weather like that,” Hege Njaa Aschim, from the Norwegian government, told The Guardian.

Far from being left to its own devices, the seed bank is now under 24-hour supervision while the Norwegians conduct a series of upgrades costing $4.4m (£3.4m). The Norwegian government said in a statement:

“When water intrudes into the outer part of the seed vault, the water is immediately pumped out again by pumps that work around the clock.”

“The seeds are completely safe and no damage has been done to the facility. Globally, the Seed Vault is, and will continue to be, the safest backup of crop diversity.”

The multimillion-pound upgrade has already involved removing an electric transformer from beneath the entrance tunnel as it was found to give off heat. Drainage ditches are being dug either side of the site’s distinctive angular doors and a waterproof wall is being installed within the entrance tunnel itself.

“The melting of the permafrost says a lot about the fact that climate change is real,” Marie Haga tells me.

“The challenge for maintaining diversity is not principally related to the permafrost in Svalbard, but is related to the fact that we can expect an increase in temperature of 3-4C in many parts of the world, and that is dramatic for food production.”

Extinction threats to plants may not gain the same coverage as that for tigers, whales or gorillas, but our growing need for agricultural produce, combined with the threat to biodiversity posed by climate change, could mean we see further pressures on harvests in the near future.

According to Stuart Thompson, senior lecturer in plant biochemistry at University of Westminster, “it is estimated that we have to increase food production by 70 per cent by 2050, and achieve this despite changing weather patterns and the spread of new crop diseases due to global warming”.

“The high-yielding crop varieties which we currently depend on were tailored to produce as much grain as possible under ideal conditions, not for resilience if conditions are less good, such as during flooding or drought.”

Hopefully the “doomsday scenario” that would require the site to act as an ultimate backup will never happen, but for today’s conservationists and agronomists, sites such as Svalbard are going to be increasingly important.

“Gene banks are not museums,” says Luis Salazar, communications manager at the Crop Trust. “They safeguard material to be ultimately used by breeders and farmers, be it to improve our crops or used directly in agriculture.”

“The Trust is helping to build a global system of ex situ conservation wherein international, regional and national gene banks across the world work towards making sure we do have conserved and available to be used this precious, global common good - the most important agro-biodiversity needed to feed a growing world.”

“And Svalbard is but one, albeit very important, element in this rational system.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments