Revealed: How Dark Age Britain was a land of saints

Exclusive: Archaeological research sheds remarkable new light on Celtic Christianity, reports David Keys

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Hundreds of people in Dark Age Celtic Britain were designated as saints after their deaths, according to new archaeological research.

Legends, place names and other traditions have long hinted at that possibility – but now remarkable new archaeological research is, for the first time, suggesting that it was true.

It also suggests that most of those saints were members of aristocratic elites, indeed it is conceivable that up to 3-4 per cent of Britain’s Dark Age Celtic aristocratic class were awarded saintly status.

The research reveals the extraordinary importance of what became a widespread British Celtic ‘cult of sainthood’. The investigation involved an analysis of hundreds of inscriptions, some of which were written in a mysterious cipher-like Dark Age script.

The phenomenon of widespread sainthood was used to consolidate Christianity among the general population – but also potentially as a way of increasing reverence for the aristocratic elites.

The research shows that the driving force behind this Dark Age cult of saints appears to have been the increased number of small monastic communities and larger monasteries which established themselves in 5th and 6th century western and northern Britain.

It seems that the aristocratic and ruling elites not only established new monasteries and convents, but also populated them with some of their sons and daughters.

The monasteries became the ‘upper class at prayer’ – and saintly status helped popularise both Christianity and its noble and royal patrons.

Saints were also useful in very practical terms too – because they were almost certainly regarded as being able to directly intercede with God to help ordinary people solve economic, health or family problems.

The new research reveals how, probably in order to serve the population’s intercession needs, scores of ‘saint consultation’ monuments were established by the side of roads and in other easily visible locations.

Archaeologist Professor Ken Dark of the University of Reading has just completed a study of 240 inscribed Dark Age stone monuments.

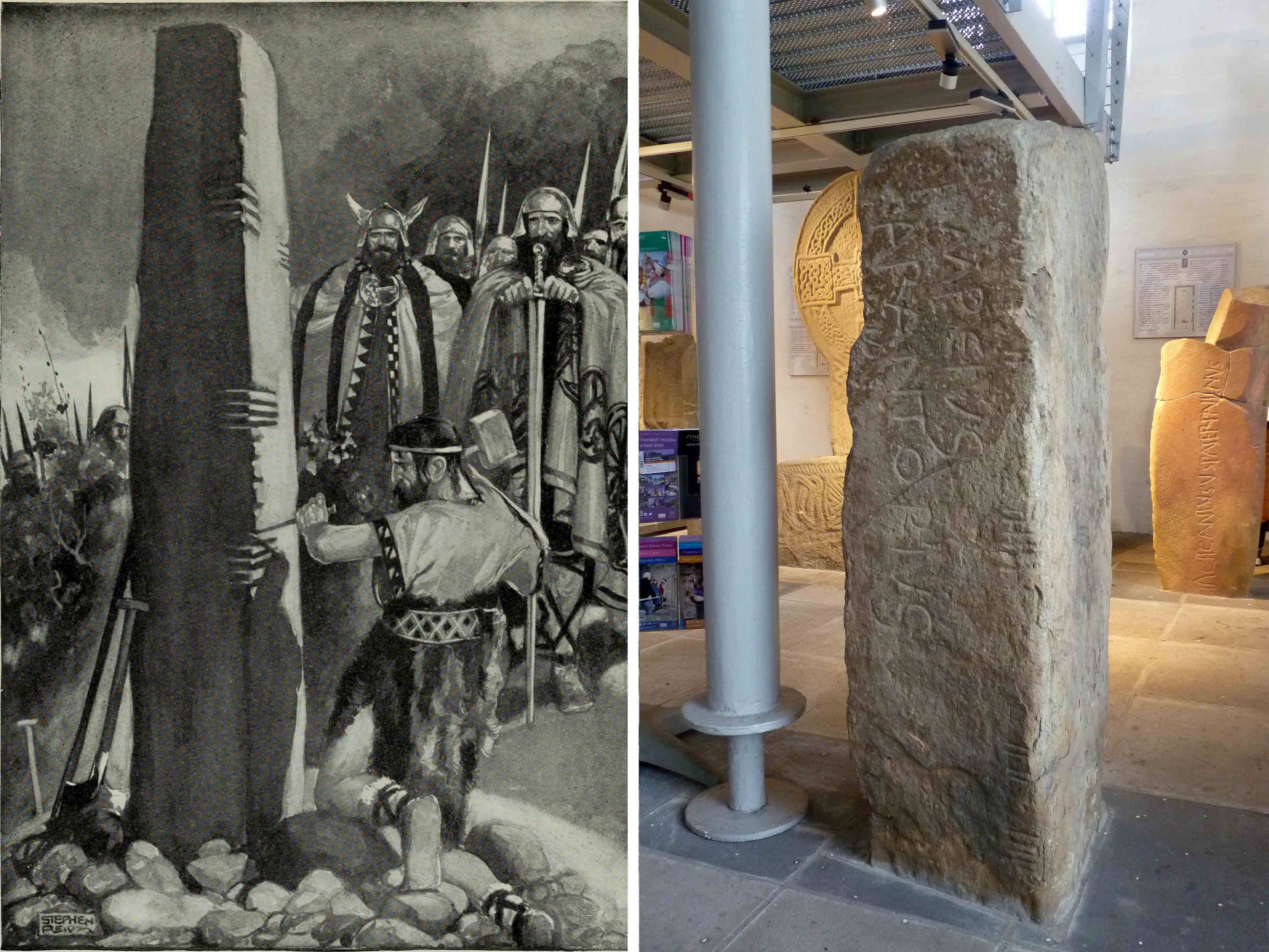

Until now, historians had thought that these inscribed stones were ordinary grave markers for warrior heroes or other prominent mainly secular individuals, but the new study reveals that they were almost certainly public monuments commemorating local saints (mostly revered monks or priests) and that they had probably been erected immediately after each individual had died.

Professor Dark’s investigation correlated inscriptions from 150 stone monuments in Wales, 20 in southern Scotland (and around Hadrian’s Wall), 40 in Cornwall and 30 from elsewhere in western England.

The survey revealed that some of the individuals had been given titles (suggesting saintly status) indicating that they were either martyrs or spiritual sages or holy men or pious devotees of famous continental saints – or even that their mortal remains were considered to be sacred relics.

At least three had royal status – but the majority were almost certainly monks or other types of cleric. Indeed, in some cases, their ecclesiastical status was mentioned in their inscriptions.

The research has increased the number of probable Celtic saints by almost 30 per cent.

However, the vast majority of the previously recorded 860 Dark Age Celtic saints (mostly first attested some five centuries later) were only known from place names, legends, and medieval church dedications.

This survey is the first time that hard historical evidence for the phenomenon (i.e. the inscriptions) has been collated.

The research also reveals that in Dark Age Britain even children could be regarded as saints.

Around 16 of the 240 newly identified probable saints were women – and its likely that some were the wives of senior ecclesiastical figures. In Dark Age British Celtic Christianity, priests (including bishops) and possibly monks were allowed to marry.

The sheer number of local saints and the ability of priests to marry were two major phenomena which differentiated Celtic British Christianity from that practised on the continent.

The research has also shown the distribution of the 240 surviving monuments to probable local Celtic saints – and has revealed specific clusters in west Cornwall, various parts of Wales (especially Pembrokeshire, the Swansea region, Anglesey, Snowdonia, the Brecon area) – and the island of Lundy in the Bristol Channel. Significantly, most of the clusters correlate with the geographical distribution of many of the 860 previously known saints who were mainly only known from church-dedications and place-names, but were otherwise normally not historically or archaeologically attested.

“By studying the inscribed stones in great detail, it has now been possible to reach radical new conclusions as to who the commemorated individuals were,” said Professor Dark, who has just published his new research in the Journal of Ecclesiastical History.

Although most of the inscriptions were written in Latin, almost 20 percent were inscribed in a mysterious now-long-forgotten Irish-originating Celtic script called Ogham.

Ogham was one of the most unusual and enigmatic scripts in the history of writing. Its letters largely consisted of differently positioned groups of horizontal lines. The phonetic value of each letter depended solely on where (and how many) otherwise identical horizontal lines were positioned relative to a single long vertical edge or other feature on a stone or other object. For instance, one horizontal line to the right of the vertical ‘axis’ represented a ‘B’, while three horizontal lines to the left of the vertical axis represented a ‘T’. Four horizontal lines (on both sides of the vertical) signified an ‘E’ – and so forth. In essence, it was similar in concept to a much later communications system, semaphore – but inscribed on stone rather than transmitted with flag signals.

It was a unique form of writing – and was perhaps originally developed for carving brief inscriptions on wood (because inscriptions on wood are more easily read if inscribed in straight lines across the grain). On stone, straight-line inscriptions are also much easier to carve than curved or complex ones.

It’s likely that this remarkable way of writing was first developed in the south of Ireland in the late 4th or early 5th century A.D. - and continued in use (for stone inscriptions) until the 7th century (although it was used occasionally and intermittently in Ireland in the margins of some manuscripts up until the 17th-century).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments