Archaeologists find world's oldest bread and new evidence of sophisticated cooking dating back 14,000 years

Discovery may represent profound change in human eating practices, away from purely nutritionally utilitarian and towards a more culturally, socially and perhaps ideologically determined culinary tradition

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Early "haute cuisine" is thousands of years older than previously thought.

Archaeologists have discovered what appears to be the birth of sophisticated cooking – at a Stone Age site in the Middle East, dating back some 14,400 years.

Until around that time, it is likely that food was primarily consumed for nutritional purposes. Throughout most of prehistory, food gathering and processing appears to have been carried out in order to ensure that food consumption was safe and provided more energy than it cost people to make. It was essentially carried out to produce a net energy gain.

But now, archaeologists have discovered the world’s oldest bread – that was cooked and probably eaten in what appears to have been some sort of ultra-early ceremonial or religious complex.

The discovery – at an archaeological site known as Shubayqa 1 in what is now desert in northeast Jordan – is particularly significant because wild cereal bread does not produce a net nutritional gain.

It would have almost certainly cost the prehistoric people at Shubayqa 1 more energy to make than they would have gained by consuming it.

It is therefore likely that it was among the very first "special" foods to be made not primarily for nutrition – but mainly for cultural and potentially social or ideological reasons.

The bread – made 3,500 years before the birth of agriculture – is from an area and a time associated with the world’s oldest monumental stone buildings (constructed between 15,500 and 14,000 years ago).

The buildings – which were not typical of the majority of houses of that era – were probably constructed for communal ceremonies and rituals (perhaps including feasting associated with celebrating or commemorating the dead). The rare stone-built complexes normally have human burials adjacent to or beneath them.

The particular building that the bread was discovered in was around eight metres in diameter – and had a well-made stone-paved interior.

In the building’s hearth, the archaeologists found evidence of food consumption (given the probable purpose of the building, potentially communal feasting).

The food debris includes gazelle, water fowl and hare bones, wild mustard seeds, charred tubers and fragments of at least three different types of unleavened flatbread. It is therefore likely that any special communal meals celebrated there involved feasting on meat and roasted tubers wrapped in or eaten with flat bread in much the same way that people still often consume food in the Middle East and South Asia today.

It is also conceivable that this probably ritualised early conception of bread in the Middle East 14,400 years ago represents the genesis of the long-standing religious importance of bread consumption in (or originally associated with) that region.

In Judaism, ritually important bread was kept in a portable House of God (a sophisticated tent known as the Tabernacle) before the first great stone temple was built in Jerusalem – and of course special bread is still eaten every Friday evening throughout the Jewish world and a type of unleavened flatbread (called matzo) is still eaten by Jews at Passover.

In Catholicism, unleavened communion bread is regarded as part of the body of Jesus – and in Lebanese Arab Christian tradition, a special bread called qurban is still used in ceremonies to commemorate the dead.

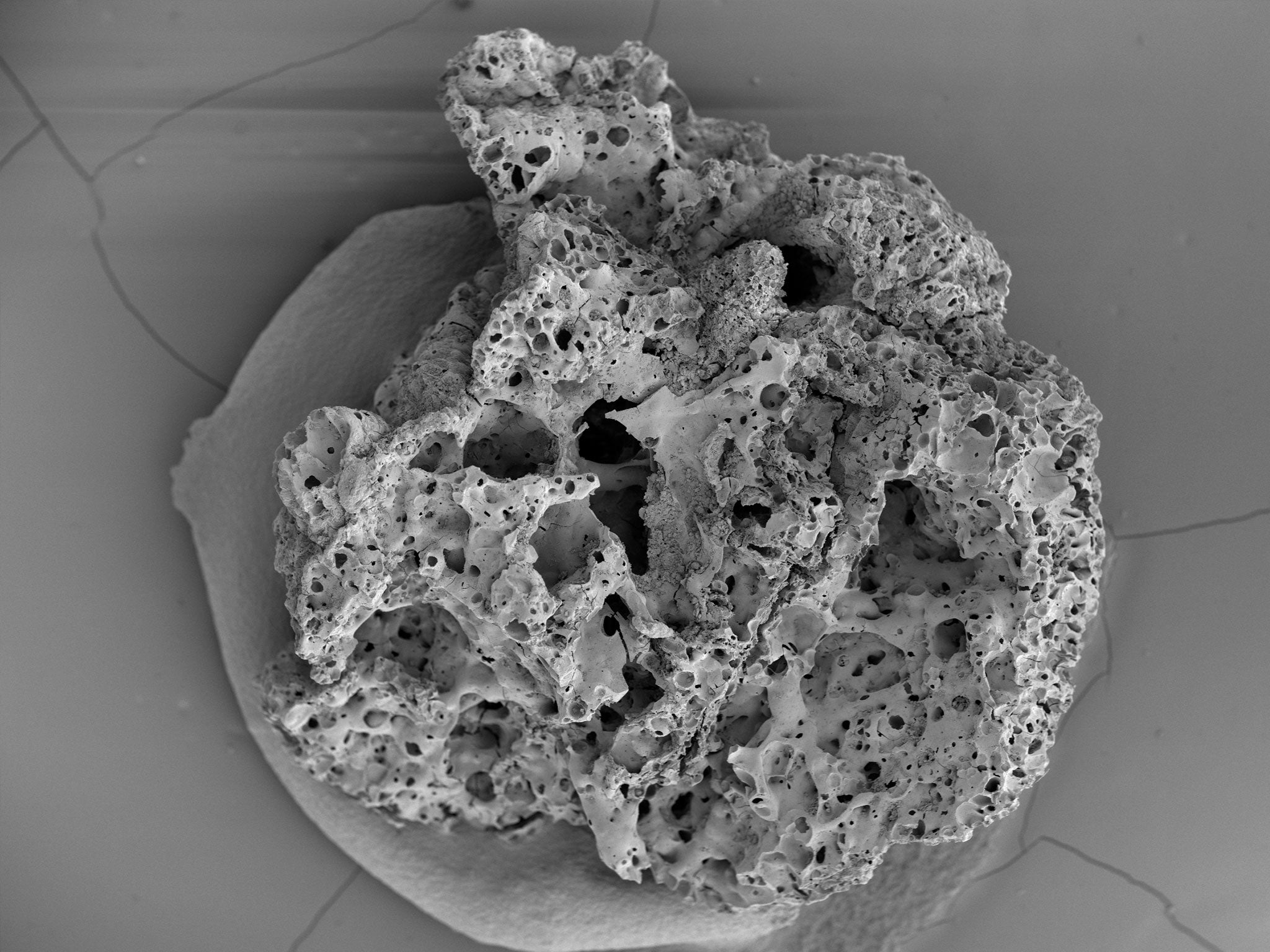

At least three or four different types of flatbread have been discovered at Shubayqa 1. A total of 254 fragments were found in the hearth of which 100 were analysed. Of these, only 24 yielded data on their composition. Of that sample, 75 per cent were made purely of wild wheat (probably wild Einkorn), 12.5 per cent purely from wild barley and 12.5 per cent from a mixture of wild wheat and the tubers of a species of the large bull-rush-like plant, sedge.

However, because lots of mustard seeds were also found in the hearth (and it is known from much later Middle Eastern evidence that such seeds were used in bread-making), it is conceivable that some of the other bread fragments at the site were made from wheat (or barley) mixed with mustard seeds.

It is likely that barley was the most common wild grass available in the Shubayqa area at that time, and yet the early bread makers at the site appear to have chosen quite deliberately, in the main, to gather wheat. That may be a very significant choice – because wild wheat seeds have much more gluten in them than wild barley and would therefore have made bread dough with a greater degree of plasticity, thus allowing the making of much thinner flatbreads. The bread fragments discovered suggest that they were successfully making flatbreads which were just 5-7 millimetres thick.

The entire process of bread-making was (and indeed still sometimes is) nutritionally relatively uneconomic. Harvesting wild cereals, separating the seeds, grinding them, making the dough, flattening the dough and cooking it was an energy and time consuming activity which would not, on consumption, have produced a net energy gain for the people of Shubayqa 1.

The Shubayqa discovery may well therefore represent a profound change in human eating practice – away from the purely nutritionally utilitarian and towards a more culturally, socially and perhaps ideologically determined culinary tradition that is the norm throughout most of the world today.

The site has been excavated by a team headed by Dr Tobias Richter of the University of Copenhagen. However, the analysis and identification of the bread was carried out by Lara Gonzalez Carretero of University College London’s Institute of Archaeology and Dr Amaia Arranz Otaegui of the University of Copenhagen.

The Institute of Archaeology’s Prof Dorian Fuller, a leading expert on prehistoric cereals, said: “This discovery demonstrates that food became something that was valued for more than just calories. It reveals that people over 14,000 years ago had begun to consume food for social, cultural and potentially ideological reasons.”

The discovery is also very important because it predates the first agriculture by some 3,500 years. All the cereals being harvested at Shubayqa 14,400 years ago were wild varieties, almost certainly growing in wild stands.

The discovery suggests that bread-making probably in the end helped motivate people to start cultivating and domesticating cereals – a development that ultimately led to the birth of agriculture. That is the opposite to what academics had previously thought. Up till now, prehistorians had believed that agriculture led to the invention of bread. The new discovery suggests that the truth is likely to have been the other way round.

“The production of a bread-based cuisine was one of the motivations behind people developing agriculture in the Middle East. It is from the Middle East that agriculture and bread spread to Europe and North Africa,” said Professor Fuller.

In the 15th millennium BC bread was almost certainly a totally new food, although the relatively rare harvesting of wild cereals for toasting and possible use in porridge form had occurred, perhaps intermittently, since around 23,000 years ago in the Middle East and in China.

“Shabayqa 1 is important not just because it has the earliest evidence for bread but also because it has some of the earliest stone buildings in the world,” said the director of the excavation, Dr Tobias Richter, associate professor of Near Eastern Archaeology at Copenhagen University.

The discovery of the world’s oldest bread at the Shubayqa 1 site is being published in the US journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The prehistoric bread discovered at Shubayqa 1 is some 5,000 years older than the previously oldest known bread, also from the Middle East.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments