Archaeologists discover bizarre artefact from long-lost fertility ritual

Painted dog penis bone, believed to be the first of its kind, is unearthed from limestone shaft in Surrey’s Ewell

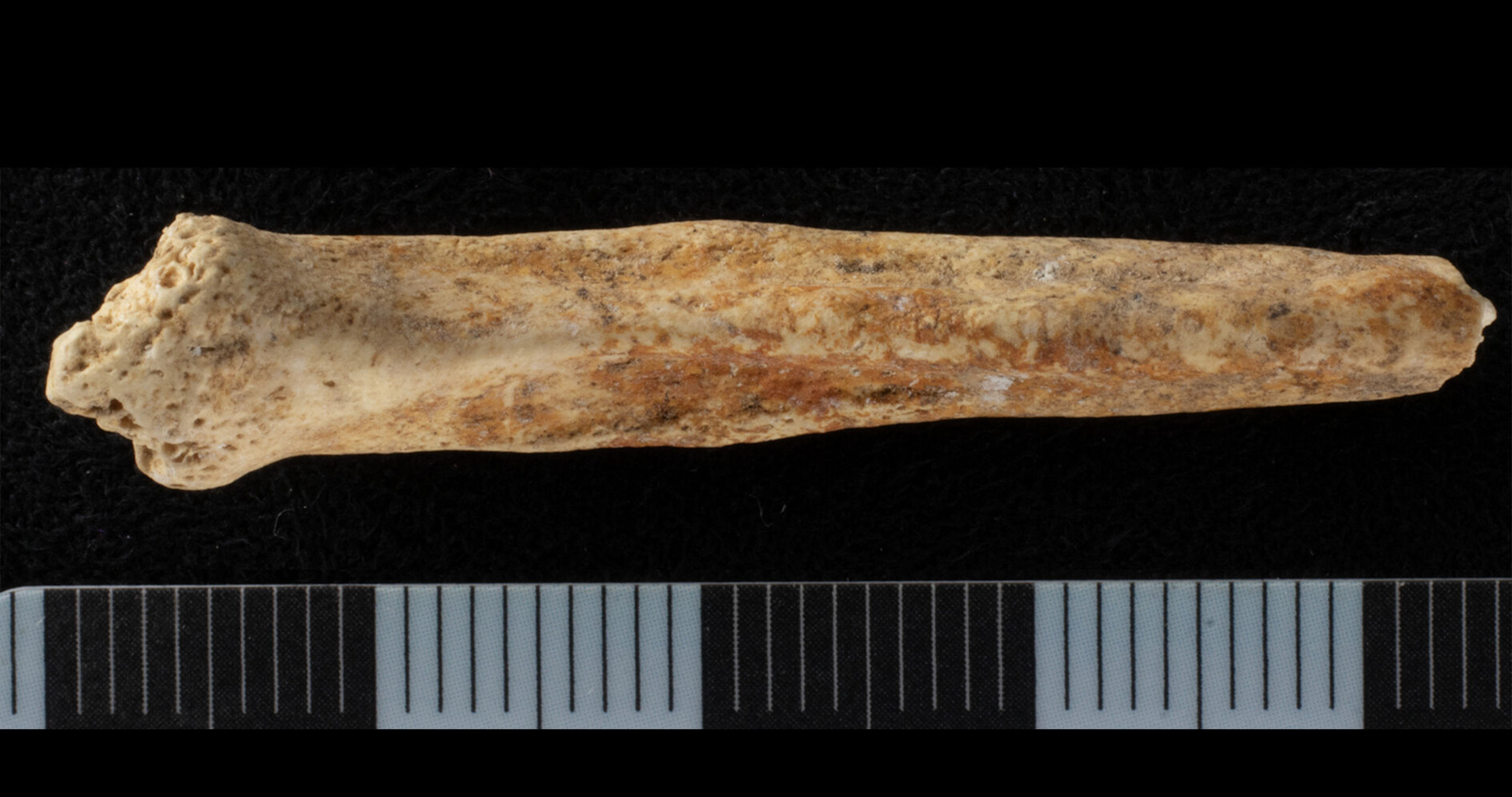

A first-of-its-kind painted dog penis bone has been discovered in a Roman quarry shaft in Surrey, an artefact that archaeologists suspect was used in a long-lost fertility ritual.

The 13ft deep limestone shaft in Surrey’s Ewell area was found in 2015 and excavations at the first century AD site have since unearthed a trove of ancient human and animal bones.

The remains unearthed at the shaft from the Romano-British era include around 300 domestic animals, including pigs, horses, cows, sheep, and dogs with a majority without any signs of butchering, burning or disease.

Canines found at the site named Nescot shaft are mostly smaller pet breeds like corgis as opposed to those used in hunting or farming, researchers say.

A new study published in the Oxford Journal of Archaeology assessed a painted dog baculum, or penis bone, found at the site which is suspected to have “potential ritual significance”.

Archaeologist Ellen Green, the study’s sole author, found that red ochre had been used to paint the dog bone even though the mineral iron oxide behind the colour was not naturally occurring at the Nescot site.

This led Dr Green to suspect red ochre was specifically chosen to pain the bone before it was thrown inside the shaft, likely as a lucky charm.

She also suspected the ritual may have been connected to fertility as a large number of animals thrown into the shaft were very young.

The shaft’s “unique assemblage” of human and animal remains – along with the first recorded instance of Romano-British use of red ochre on bone – led her to conclude the region’s early inhabitants sought “cosmological connections to fertility” through the ritual.

“While the idea of ritual shafts being associated with fertility is not new, this study is one of the first to draw from multiple strands of evidence to support the idea,” Dr Green said.

The ritual may have been tied to ideas of new life and the agricultural cycle due to the seasonality and birth timing of the animals used.

“In this case a feature full of the dead becomes a potential symbol of new life and regeneration, adding to the ever-growing tapestry of Romano-British belief,” the study noted.

“While it is impossible to know for sure the reasons behind the deposition of humans and animals within the disused quarry shaft over approximately half a century, the evidence does support a link to ideas of abundance, new life and the agricultural cycle.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks