A bone to pick with the Bard: Richard III was NOT a hunchback

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An adolescent growth spurt that went wrong caused King Richard III’s physical deformity but it did not give him a hunchback, a limp or a withered arm as commonly portrayed in Shakespearian renditions of the last Plantagenet king, a study has found.

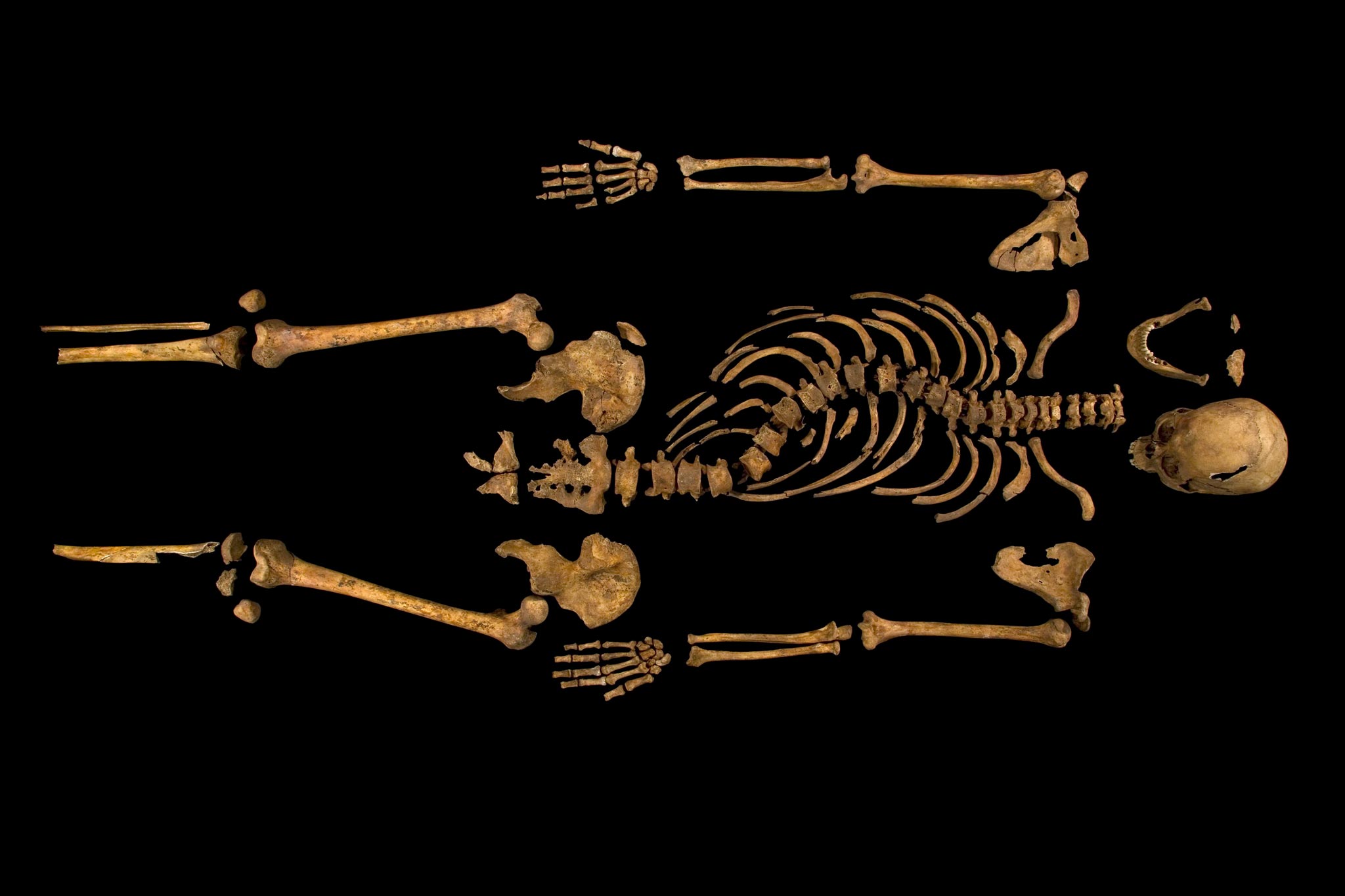

Medical researchers have diagnosed that Richard, whose skeletal remains were discovered beneath a council car park in Leicester last year, suffered from adolescent-onset scoliosis, when the spine curves to one side, which he developed in late childhood.

A detailed CT scan of the king’s vertebrae has enabled scientists to reconstruct his deformity on computer, enabling them to build a three-dimensional polymer model of his spine showing a pronounced spiral curvature to his right side in the middle of his back at the level of his chest.

Although the deformity is marked by modern standards, the scientists believe it would not have affected his ability to carry out physical activities such as walking or riding a horse, and it may have even been easily disguised with clothes or body armour.

“The physical deformity produced by Richard’s scoliosis was probably slight as he had a well balanced curve of the spine,” said Piers Mitchell of Cambridge University who helped to carry out the analysis with colleagues from the universities of Leicester and Loughborough.

“His trunk would have been short relative to the length of his limbs, and his right shoulder a little higher than the left. However, a good tailor to adjust his clothing and custom-made armour could have minimised the visual impact of this,” Dr Mitchell said.

Shakespeare famously described Richard III as “bunch-backed” and is called “crookback” three times in Henry VI, Part 3. Shakespeare also wrote Richard’s own description of himself with “an envious mountain on my back”, which was widely interpreted as meaning that he was a hunchback with a limp and a withered arm.

However, the detailed description of Richard’s real condition, published in The Lancet, shows that he was none of these and almost certainly did not walk with a limp or have a withered arm as his limbs were evenly proportioned.

Nevertheless, his scoliosis, which probably started after the age of 10, did result in his right shoulder being higher than his left and his torso being relatively short compared to his arms and legs. His head and neck, however, would have been straight and not tilted to one side, Dr Mitchel said.

“The middle part of the spine in the thoracic region was curved to the right and the bones were in a slight spiral configuration. Looking at the 3D model we could see that it had the classic spiral shape of the scoliosis that children get from idiopathic adolescent-onset scoliosis,” he said.

“This is the kind of scoliosis that people get when they hit the adolescent growth spurt. When their spine grows really fast and if it can’t be controlled well enough it spirals off into a deformity in their back,” he explained.

The angle of the spiral curve in his spine suggests that Richard was able to exercise and function normally given that his lungs were already well developed at the time of onset of his scoliosis. Richard may not even have suffered much pain – patients with the same spinal curvature today are only at about twice the risk of back pain than people with healthy spines, Dr Mitchel said.

Richard died at the battle of Bosworth in 1485, the last English king to die leading his soldiers, and his naked corpse was thrown over the back of a horse and taken to Leicester where it was buried in the Franciscan convent of Grey Friars – where it was later excavated from beneath a car park covering the site.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments