Deadly mind-controlling weapon that allows predatory fungus to turn ants into ‘zombies’ discovered

Chemicals used by parasitic fungi to drives insects from nests discovered by scientists

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A chemical weapon used by deadly fungi to control ant behaviour has been identified, revealing the cause of the “zombie”-like behaviour that has been seen to drive them from their nests.

The discovery reveals how the fungi gain the upper hand in an arms race that culminates in the insects being sent to die on the forest floor.

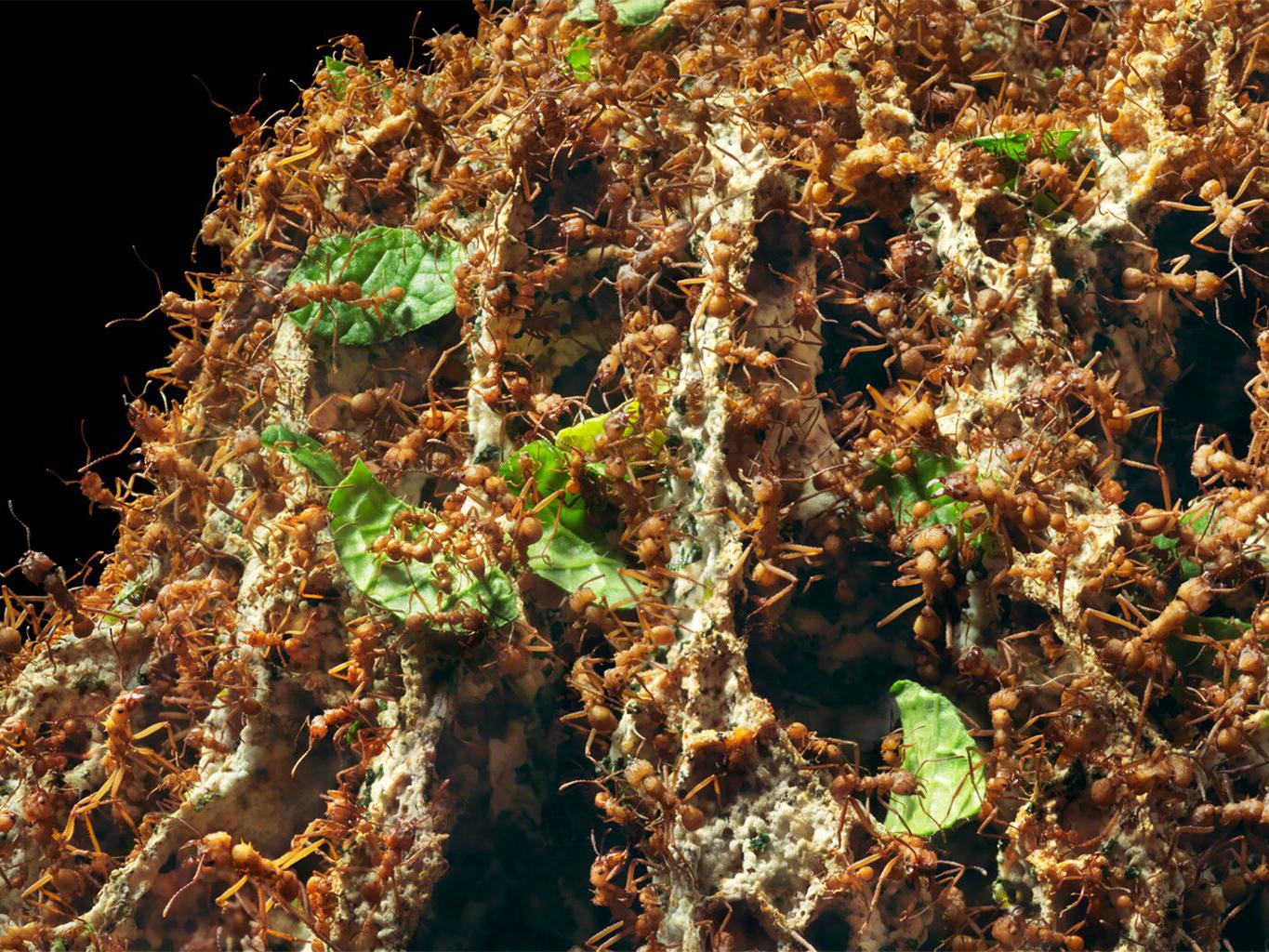

Leafcutter ants grow fungus gardens that provide a food source for their young, using chewed-up leaves as compost.

However, their gardens are threatened by the parasitic Escovopsis fungus, which also feeds on this nutritious food source.

This parasite is normally kept in check by the ants’ natural defences – but when it breaks through it devastates the ants' farms, causing entire colonies to collapse.

"Leafcutter ants are superb farmers. They patrol their gardens, remove foreign fungi and use antibiotic-producing bacteria on their bodies to kill off parasites – effectively using them as weedkillers,” said Professor Matt Hutchings, from the University of East Anglia.

"But the way in which Escovopsis succeeds in getting through their defences is not well understood."

When the fungus does succeed in infecting the ants, it forces the insects to stop maintaining their gardens and ultimately flee to the forest floor, where they die. This allows the fungus to infect the recently abandoned gardens.

This mechanism is thought to be similar to that used by the so-called “zombie ant” fungus of Brazilian and Thai rainforests, which forces ants to abandon their nests and move to areas where fungal spores can effectively spread.

To reveal the chemical mechanisms at the heart of the leafcutter ant-fungus struggle, the researchers took samples of the cultivated fungus from leafcutter ant colonies collected in Panama.

They then infected these samples with the parasite, and identified two molecule groups that seemed to be significant.

The first line of attack involved a molecule that killed off the antifungal-producing bacteria on the ants' bodies, while the second consisted of a molecule that modified the ants’ behaviour.

"We think the Escovopsis pathogen is always present in or around the nests and kept at bay by the ants' constant gardening and chemical defences,” said Professor Barrie Wilkinson, who led the project at the John Innes Centre.

"But when something unusual happens – a drought, or other environmental change perhaps – the parasite may gain a foothold and start increasing the levels of the chemical weapon compounds that cause behaviour changes and decrease the ants' weeding efficiency in their gardens.

"From then on you have an escalating situation which leads to the appearance of dead ants, and the pathogen taking over, so the remaining ants eventually abandon the nest."

The findings were published in the journal Nature Commuications.

The struggle between ants and parasitic fungi, with both competing for the same food source, appears to have been playing out for millions of years.

Over this time, each player has evolved ever-more complex weaponry and defences. Previous research suggests that the leafcutter ants are fighting back against this weak spot in their armour by acquiring additional bacteria from the soil to attack the parasites.

The scientists speculated that understanding this arms race between an animal and an aggressive infectious disease could help understand the dynamics of antibiotic resistance in humans.

"This study illustrates how important it is to gain insight into the diverse functions of natural products in nature," said Professor Christian Hertweck from the Leibniz Institute for Natural Product Research and Infection Biology, who participated in the study.

“Not only from an ecological perspective but also with a pharmaceutical application in mind."

Besides applications in humans, understanding how some organisms are able to overpower the redoubtable defences of an ant colony could help scientists develop new insecticides to control invasive ant species.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments