Groundbreaking new way of fighting antibiotic-resistant bacteria discovered by scientists

Exploiting a weakness in the wall surrounding disease-causing microbes could open the door to new drugs and revitalise old ones

Scientists have identified a weakness in disease-causing bacteria that could be used to develop drugs that will overcome antibiotic resistance.

The discovery could also give a new lease of life to existing antibiotics that have fallen out of use because they are no longer effective.

Antibiotic resistance has been described as a “global health emergency” by the World Health Organisation. England’s chief medical officer Professor Dame Sally Davies has warned of a “post-antibiotic apocalypse” unless new drugs are developed.

The new study, carried out by an international team of researchers and published in the journal PLOS Biology, identified a weakness in the protective “wall” surrounding bacterial cells, which could be targeted by antibiotics.

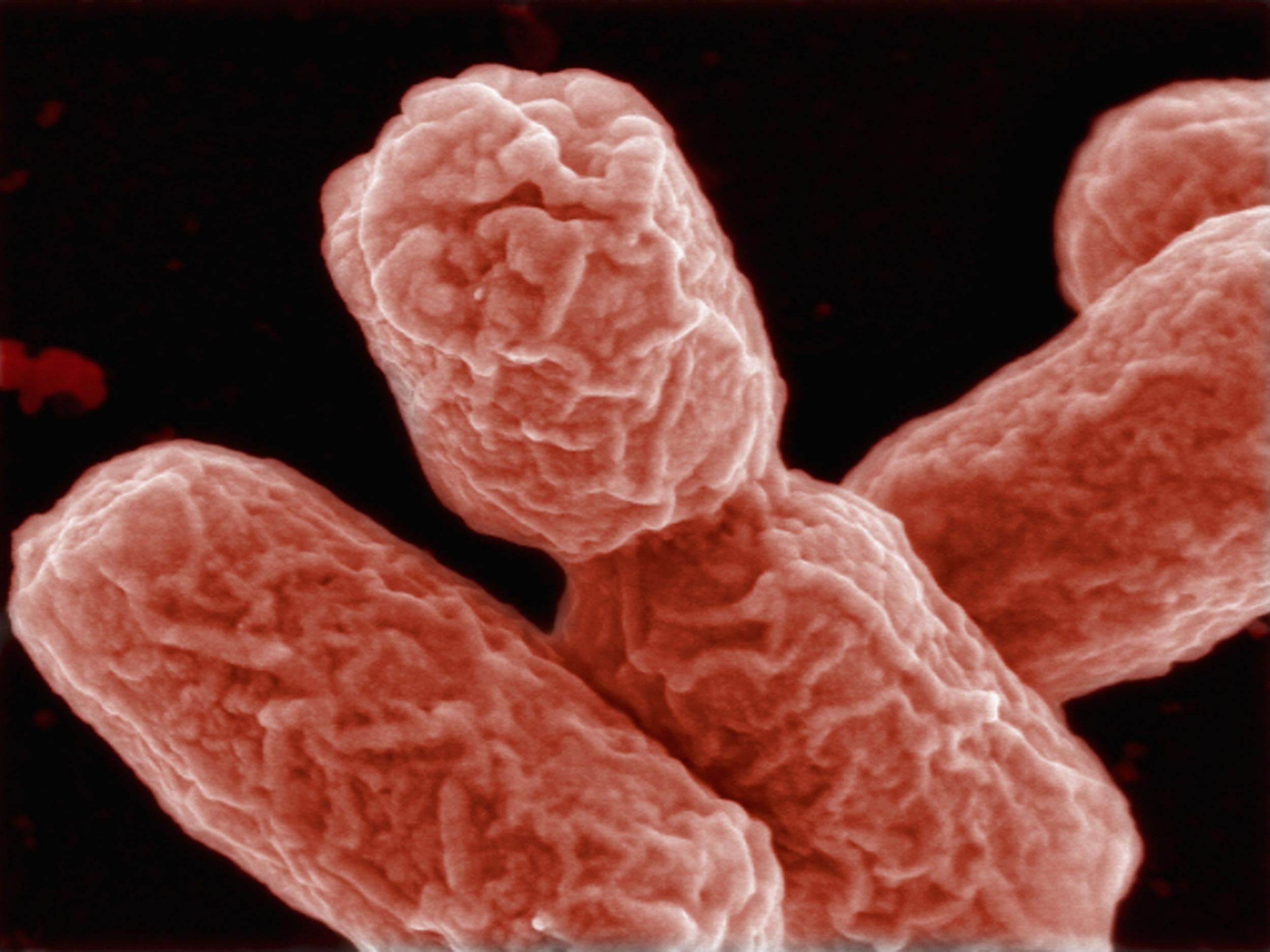

“Gram-negative” bacteria – the group responsible for diseases including bubonic plague and gonorrhoea – are surrounded by two membranes known collectively as the envelope.

By disrupting the connections in this protective wall, the scientists found they could diminish the bacteria’s protective response to antibiotics, which is mediated via protein molecules inside the membranes.

“On the wall there is a protein that serves as a guard, and so when there are antibiotics coming this protein will feel that and will then turn inside and reach another protein on the inner membrane, and they will communicate,” said Professor Jean-François Collet, of the Université Catholique de Louvain, who co-authored the study.

This communication allows bacteria to develop resistance to antibiotics. Using these communication channels, bacteria can detect and fix damage caused by antibiotics, or even actively remove the drug after it has entered the cell.

“We showed that if you increase the distance between the two walls, the protein will turn inside and try to reach its friends on the inner wall, but it will not be able to reach them,” said Prof Collet.

There are other proteins controlling the distance between membranes, and Prof Collet and his collaborators found that tampering with them caused a communication breakdown in the bacteria.

“By messing up those proteins we can disturb the overall architecture of the cell envelope,” he said.

Prof Collet is currently working with drug companies to develop new substances that are able to disturb bacterial cell walls and ultimately fight disease.

“This work identifies a potential new target for novel antibacterial therapies that could be used to treat bacteria that are resistant to other classes of antibiotics, but there is a long way to go before this could lead to new drugs,” said Dr Richard Stabler, co-director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine’s Antimicrobial Resistance Centre, who was not involved with the study.

As with any new drug, antibiotics that mess with bacteria cell walls would need to go through a long process to test their safety and effectiveness before being widely used.

However, according to Dr Clare Taylor, general secretary of the Society for Applied Microbiology - who was also not involved with the study- tampering with the sensing ability of bacteria could also give antibiotics that are falling out of use due to resistance a new lease of life.

“If you disrupt that membrane-sensing potential in a bacterium, it switches off its ability to remove the antibiotic,” she said. “That could mean that a lot of antibiotics could come back into play.”

While this would save the effort of developing new drugs, it does not mean we could rely exclusively on existing drugs.

“I suspect that in time bacteria would find a way around them,” said Dr Taylor. “It’s a bit like Jurassic Park: life finds a way”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks