New antibiotic capable of killing superbugs discovered inside the human nose

There have been no new antibiotics discovered for 30 years

A new type of antibiotic that is capable of fighting off some superbugs has been discovered in the human nose.

The new drug, named lugdunin, originates from bacteria present in human nostrils. Importantly, it gave no indications of allowing the bacteria it attacks to mutate and develop resistance.

A human form of the drug has not yet been developed – it has only been tested on mice – but if successfully formulated, it would be a hugely significant scientific breakthrough.

New antibiotics have not been developed since the 1980s and antimicrobial resistance to drugs is a growing concern. There are fears the world could return to the days before penicillin was turned into an effective drug in the 1930s, when a scratch in the garden could prove fatal.

Most existing antibiotics are sourced from the soil, where there is a constant war between different microorganisms.

But lugdunin originated from a type of bacteria called Staphylococcus lugdunensis, which is found in about nine per cent of human noses.

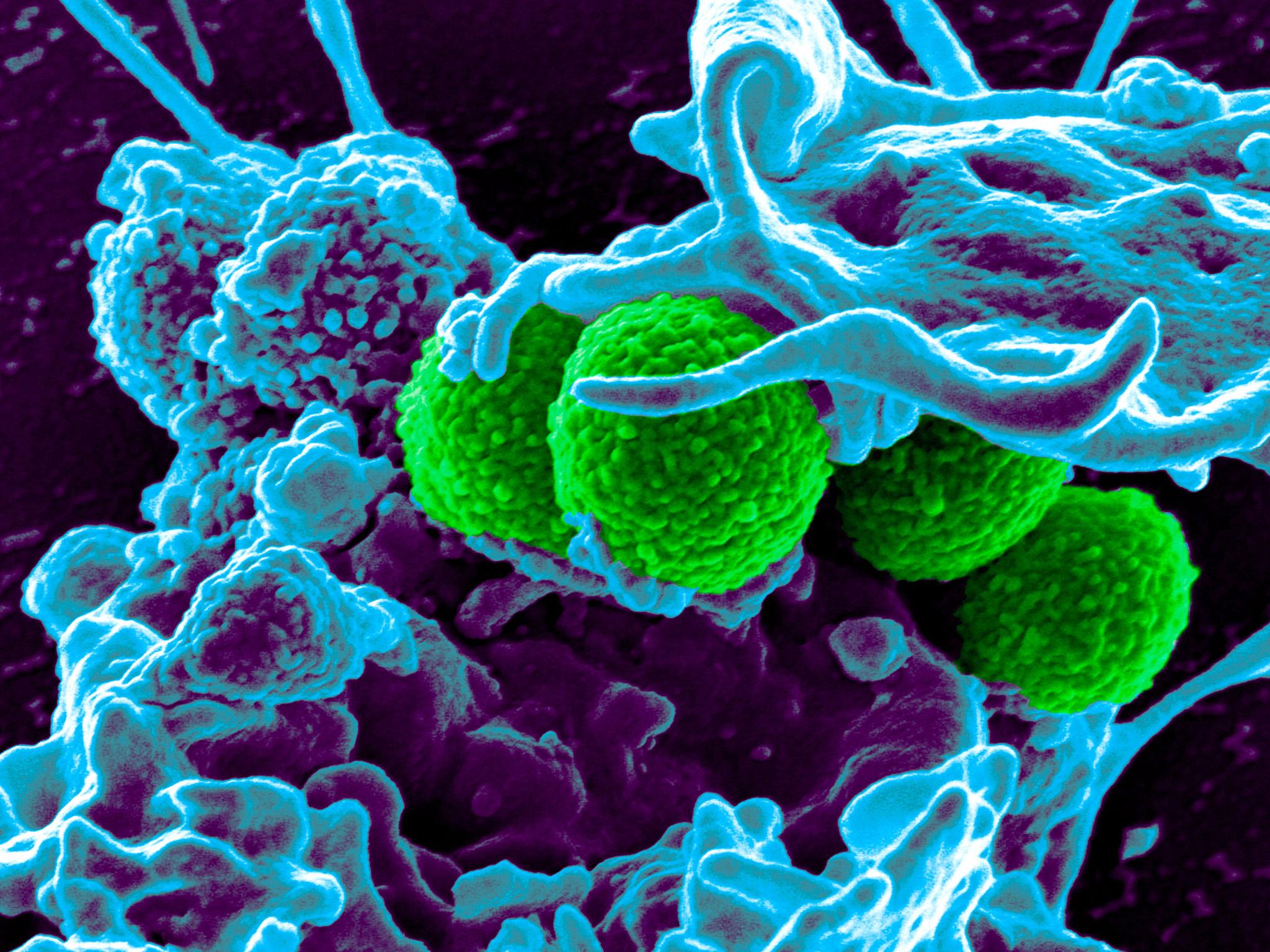

Scientists from the University of Tübingen in Germany made the discovery while examining the Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, which can cause drug-resistant infections like MRSA.

“If you want to keep the bacteria in check, you need to understand their lifestyle,” said Dr Andreas Peschel, who worked on the study. “And to understand that, we also looked at its competitors.”

Dr Peschel’s team discovered people who had S. lugdunensis bacteria naturally present in their body were six times less likely to host S. aureus than people without S. lugdunensis.

In a healthy body, different bacteria in the body compete and keep each other in check, providing a balance. With this in mind, the researchers identified a specific gene in S. lugdunensis which could combat S. aureus in its various guises.

Using this gene, the scientists developed the antibiotic lugdunin. They used it on mice with skin lesions infected with S. aureus bacteria and found it cured the infection in both in the upper and deeper layers of the flesh.

"Some of the animals were completely clear, no single cell of the bacterium was detectable,” researcher Dr Bernhard Krismer told the BBC.

"Others were reduced, but still contained some bacteria and we also saw that the compound penetrated the tissue and acted on the deeper layer of the skin."

While normal antibiotics attack bacteria by causing chemical reactions with its cells, lugdunin attacks the cell membrane, although how this works is not full understood.

But lugdunin killed MRSA and several other antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria.

Crucially, S. aureus did not mutate to become a strain resistant to lugdunin during the trials. “We never found spontaneous mutants,” said Dr Peschel.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks