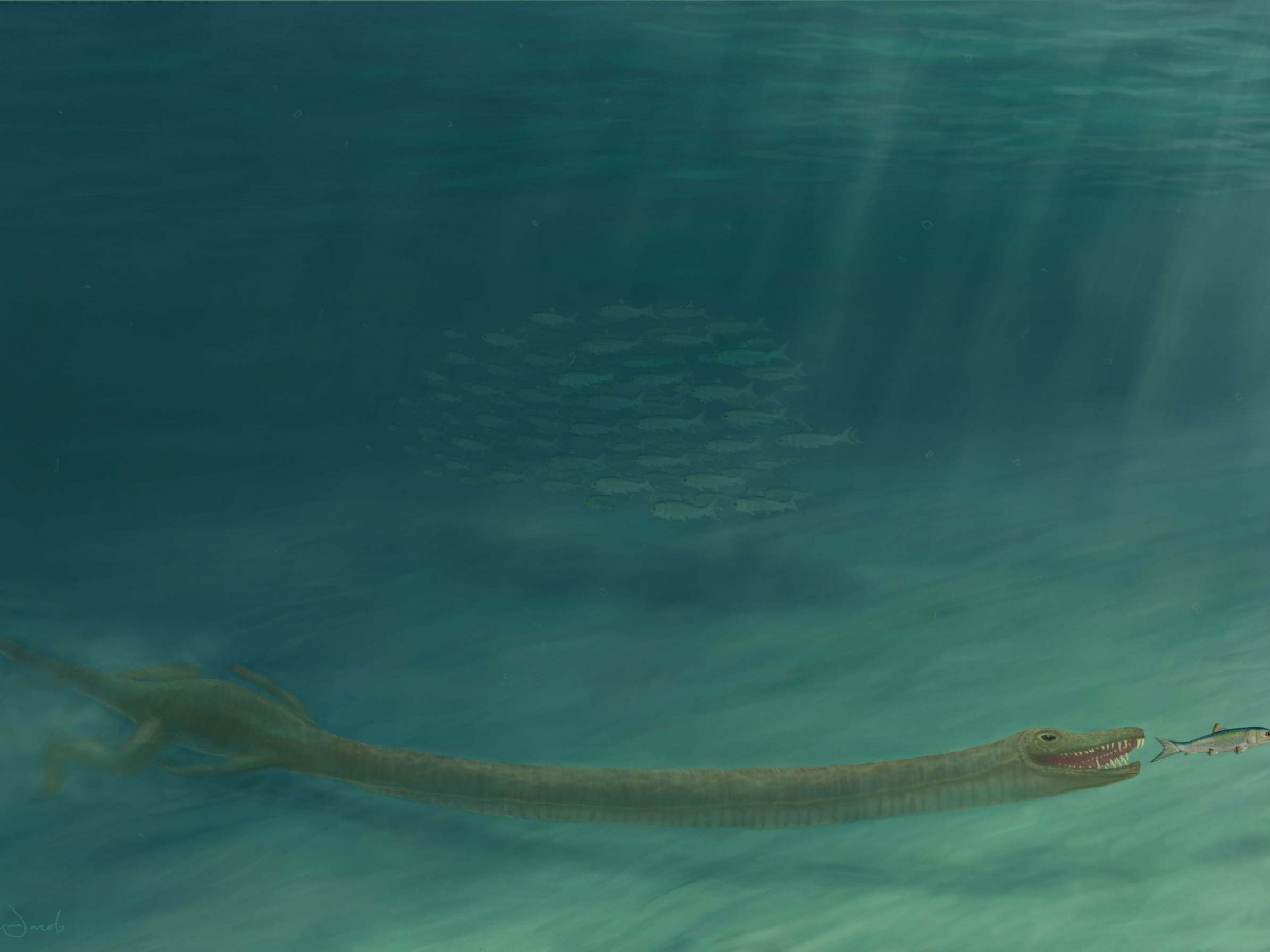

Scientists solve mystery of how an ancient reptile moved around with a neck three times longer than its body

A reconstruction of the creature's skull revealed clear signs it lived in the sea

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have solved the mystery of how a 242-million-year-old reptile with a neck three times the length of its torso moved around, discovering that it lived in the ocean.

Paleontologists have been puzzled ever since fossils of the creature, which is part of the Tanystropheus genus, were first discovered in 1852, as they were unable to work out how the animal could have supported the weight of its neck.

The creature's "bizarre body didn't make things clear one way or the other", researchers said, and its giraffe-like neck left scientists unsure over whether it lived on land or in the sea.

The puzzle was solved when a new study by the University of Zurich reconstructed the reptile's skull, revealing "several very clear adaptations for life in water".

Olivier Rieppel, a paleontologist at the Field Museum in Chicago and one of the authors on the study, said: "That neck doesn't make sense in a terrestrial environment. It's just an awkward structure to carry around.”

Mr Rieppel described the creature as “a stubby crocodile with a very, very long neck”.

The scan showed that the 20-foot reptile had nostrils on the top of its snout and curved, interlocked teeth – both indications of an animal that would have hunted in the water.

Stephan Spiekman, a paleontologist at the University of Zurich in Switzerland and lead author on the study, said: “It likely hunted by stealthily approaching its prey in murky water using its small head and very long neck to remain hidden.”

Tanystropheus fossils were discovered in on the border between Switzerland and Italy.

Nearby, scientists found fossils of a creature that looked similar, but was only 4-feet long, leading them to wonder if they were juveniles or a different species. Analysis revealed they were fully grown, and therefore a separate species.

Nick Fraser, keeper of natural sciences at National Museums Scotland and a co-author on the paper, said: "It is hugely significant to discover that there were two quite separate species of this bizarrely long-necked reptile who swam and lived alongside each other in the coastal waters of the great sea of Tethys approximately 240 million years ago."

Mr Spiekman added: "These two closely related species had evolved to use different food sources in the same environment.

He explained the small species probably ate small shelled creatures such as shrimp, while the large species will have fed on fish and squid.

"This is really remarkable, because we expected the bizarre neck of Tanystropheus to be specialised for a single task, like the neck of a giraffe.

"But actually, it allowed for several lifestyles. This completely changes the way we look at this animal."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments