Air and water pollution linked to changes in human sex ratio at birth, study finds

Researchers do not find a cause-effect relationship between sex ratio at birth and pollutants

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The presence of different air and water pollutants in a region could be linked to changes in the human sex ratio at birth, suggests a new study that evaluated over six million births in the US and Sweden.

The analysis, published in the journal PLoS Computational Biology on Thursday, found that sex ratio at birth (SRB) was linked to numerous pollutants, but was not associated with seasons, ambient temperature, violent crime rates, unemployment rates or commute times.

SRB was defined by the study as the percentage of newborns who are boys.

“Increased levels of a diverse array of air and water pollutants were associated with lower SRBs, including increased levels of industrial and agricultural activity, which served as proxies for water pollution,” the researchers, led by Andrey Rzhetsky of the University of Chicago, noted in the study.

They, however, found that several environmental toxins were also linked to higher SRBs.

Scientists analysed records from the IBM Health MarketScan insurance claim dataset on more than three million births in the US from 2003 to 2011, as well as records on more than 3 million births in the Swedish National Patient Register from 1983 to 2013.

They also assessed additional data on weather and pollutants at the time of each birth that was available from other national databases.

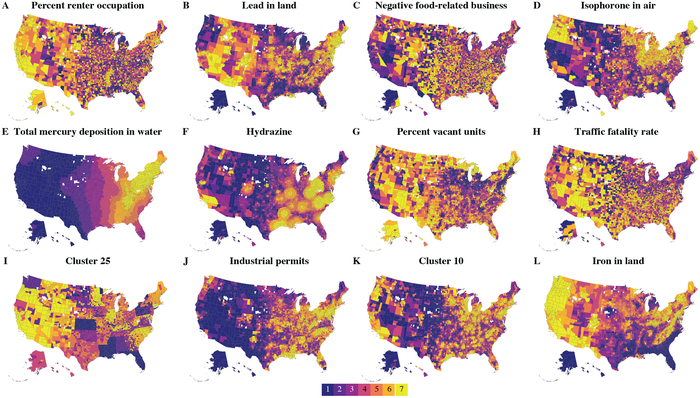

The study found that – along with factors such as extreme droughts, traffic fatality rates, industrial permits and vacant units in an area – levels of pollutants including iron, lead, mercury, carbon monoxide, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), aluminium in the air and chromium and arsenic in water were linked to changes in SRB.

While the research found a correlation between the two parameters, they could not determine whether or not there was a cause-effect relationship between SRB and pollutants.

At a biological level, they said SRB was affected by hormonal factors that specifically terminated female or male embryos during pregnancy.

“We propose to interpret these results simply as public health indicators awaiting further empirical confirmation rather than as implicated in (adaptive) sexual selection mechanisms,” the scientists wrote in the study.

Citing the limitations of the study, the researchers said they could not access data on the sex of stillbirths.

“Ideally, each SRB-pollutant association could now be followed up with experimental work using human cell lines to dissect the underlying mechanism,” Dr Rzhetsky said in a statement.

The scientists called for further studies to understand the link between pollution and changes in SRB, adding that the findings could encourage policymakers to “decide to make steps toward reducing environmental pollution.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments