Ethics of AI: Should sentient robots have the same rights as humans?

With the growing pursuit of artificial intelligence, questions about our moral duty towards new technology could become increasingly important

Imagine a world where humans coexisted with beings who, like us, had minds, thoughts, feelings, self-conscious awareness and the capacity to perform purposeful actions – but, unlike us, these beings had artificial mechanical bodies that could be switched on and off.

That brave new world would throw up many issues as we came to terms with our robot counterparts as part and parcel of everyday life. How should we behave towards them? What moral duties would we have? What moral rights would such non-human persons have? Would it be morally permissible to try to thwart their emergence? Or would we have a duty to promote and foster their existence?

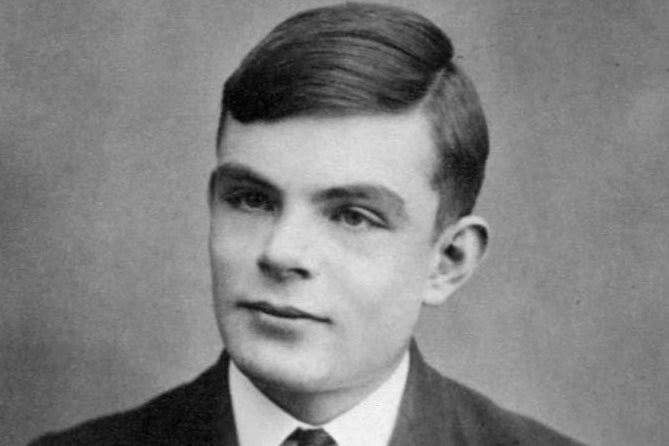

Intriguing ethical questions such as these are raised in Ian McEwan’s recent novel, Machines Like Me, in which Alan Turing lives a long successful life and explosively propels the development of artificial intelligence (AI) that leads to the creation of “a manufactured human with plausible intelligence and looks, believable motion and shifts of expression”.

As intellectual speculation, to consider the ethics of the treatment of rational, sentient machines is interesting. But two common arguments might suggest that the matter has no practical relevance and any ethical questions need not be taken seriously.

The first is that such artificial people could not possibly exist. The second, often raised in the abortion debate, is that only persons who have living and independently viable human bodies are due moral respect and are worthy of moral consideration. As we shall see, these arguments are debatable.

Mind, matter and emergent properties

We might suppose that mental phenomena – consciousness, thoughts, feelings and so on, are somehow different from the stuff that constitutes computers and other machines manufactured by humans. And we might suppose that material brains and material machines are fundamentally different from conscious minds. But whether or not such suppositions are true – and I think that they are – it does not follow that sentient, consciously aware, artificially produced people are not possible.

The French sociologist Emile Durkheim argued very convincingly that we should beware of simplistic arguments in social science. Social phenomena, such as language, could not exist without the interaction of individual human beings with their particular psychological and biological features. But it does not follow that the resultant social phenomena – or “emergent properties” – can be completely and correctly explained solely in terms of these features.

The same point about the possibility of emergent properties applies to all sciences. There could not be, for instance, computers of the sort I am now working at without the pieces of plastic, wires, silicon chips and so forth that make up the machine. Still, the operations of a computer cannot be explained solely in terms of the features of these individual components. Once these components are combined and interact in particular ways with electricity, a phenomenon of a new sort emerges: a computer. Similarly, once computers are combined and interact in particular ways, the internet is created. But clearly, the internet is a different sort of phenomenon from a tangible, physical computer.

In a similar way, we need not suppose that minds are reducible to brains, molecules, atoms or any other physical elements that are required for them to function. They might be entities of a different sort that emerge from particular interactions and combinations of them.

There’s no obvious logical reason why conscious awareness of the sort that human beings possess – the capacity to think and make decisions – could not appear in a human machine some day. Whether it is physically possible and, therefore likely to actually happen, is open to debate.

Do machines deserve our consideration?

It doesn’t seem controversial to say that we shouldn’t slander dead people or wantonly destroy the planet so that future generations of unborn people are unable to enjoy it as we have. Both groups are due moral respect and consideration. They should be regarded as potential objects of our moral duties and potential recipients of our benevolence.

But the dead and the yet to be born do not have viable bodies of any sort – whether natural or artificial. To deny conscious persons moral respect and consideration on the grounds that they had artificial rather than natural bodies would seem to be arbitrary and whimsical. It would require a justification, and it is not obvious what that might be.

One day, maybe sooner than we think, a consideration of the ethics of the treatment of rational, sentient machines might turn out to be more than an abstract academic exercise.

Hugh McLachlan is a professor emeritus of applied philosophy at Glasgow Caledonian University. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments