A valuable weapon in war against drug-resistant superbugs: Antibiotic offers hope

Tests show that drug is effective against the same kind of chronic bacterial infections that have killed hospital patients

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A new kind of antibiotic that causes microbes to digest themselves has been developed by scientists who believe it could become a valuable weapon in the war against drug-resistant “superbugs”.

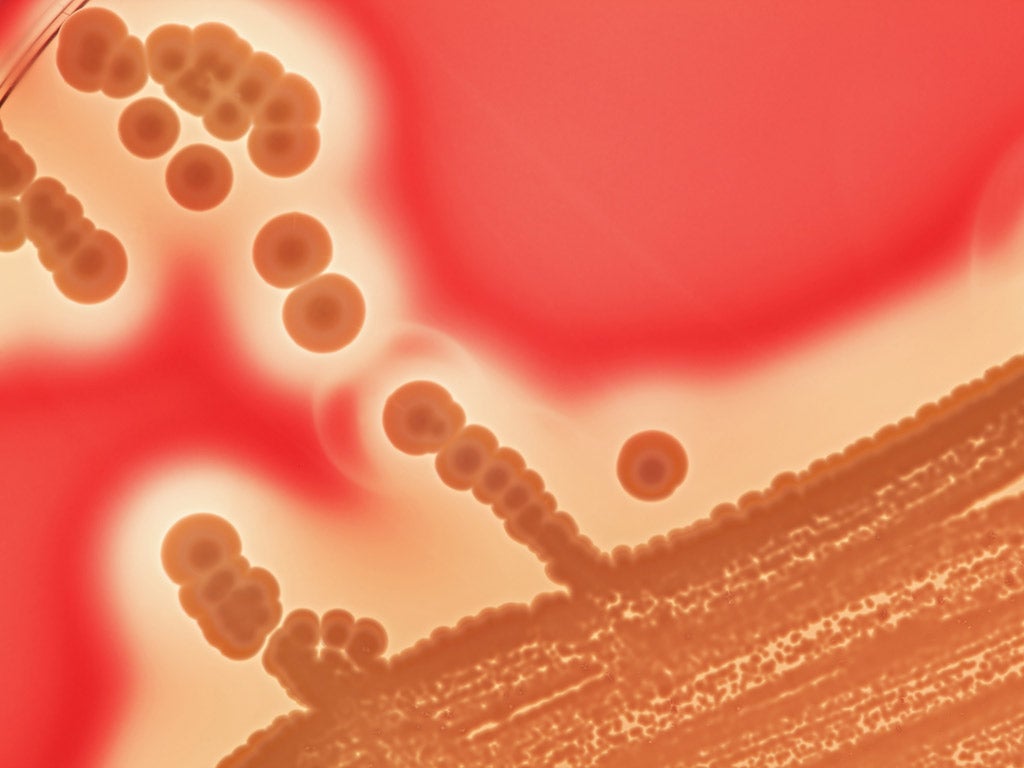

Laboratory tests show that the drug is effective against persistent strains of the Staphylococcus bacterium and is able to cure laboratory mice of the same kind of chronic bacterial infections that have killed hospital patients.

Kim Lewis of Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts, said that the drug, called acyldepsipeptide (ADEP4), works by activating an enzyme within the dormant “persister” cells of the bacteria, which causes these hardened microbial cells to self-digest.

“Persister cells don’t grow. They shut down their metabolism and in order for antibiotics to work against bacteria, the microbes must grow. ADEP4 essentially forces the cells to self-digest. The compound has an ability to sterilise an infection,” Dr Lewis said.

ADEP4 activates a protease enzyme that breaks down proteins within bacteria. However, resistance soon develops against the drug, which is why it was abandoned by the drug industry in the 1980s as a possible antibiotic, he said.

The study, published in the journal Nature, demonstrated however that when ADEP4 is used in conjunction with a conventional antibiotic, such as rifampicin, it is very effective at ridding an infection of the persister cells that are often left untouched by the treatment.

“They become susceptible to killing by any antibiotic essentially. One of the major causes of drug resistance is a large, lingering population of pathogens which happens in patients with chronic infections,” Dr Lewis said.

“If you can rapidly sterilise and get rid of that large population, you then get rid of an enormous source of resistance acquisition,” he said.

Kenn Gerdes of Newcastle University and Hanne Ingmer of the University of Copenhagen said in an accompanying article in Nature that the results were “remarkable” and offer hope for a new way of tackling resistant bacterial infections.

“This growing body of results generates hope that antibiotics for the treatment of persistent infections will be available in the future,” they say.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments