A brain scan to tell if you’re depressed – and what treatment is needed

Depression may be patterned to certain underlying brain structures

We currently diagnose depression based on what individuals tell us about their feelings – or those of their loved ones. People with depression usually describe feeling sad or say they are unable to enjoy the things they used to. But in many cases they don’t actually realise that they are clinically depressed – or feel uncomfortable talking to a health professional about it.

Such cases pose an important problem as untreated depression can hugely interfere with someone’s life, significantly increasing the risk of suicide. Currently, it is difficult to help people who are not able or willing to communicate how they feel, as there are no biological markers for the condition. But we have managed to identify a network of brain regions that is affected in people with depression – raising hope that brain scans could soon be used to diagnose it.

Depression has been recognised as an illness for centuries and was initially called melancholia – then believed to be caused by an excess of “black bile”. We now recognise that there are genetic as well as environmental factors that increase the risk of depression. For example, it occurs more frequently in certain families and in children who have suffered from abuse. We are also beginning to identify genes that are associated with the development of depression.

There are several physical symptoms of depression, including a reduction in appetite and weight loss. But the trouble is that these could be caused by a variety of conditions. Also, people can be affected in different ways – some may notice an increase rather than a decrease in appetite, for example.

Problems with sleep are also common. Many people wake up in the middle of the night and then have trouble getting back to sleep. Others may be sleeping more than they usually do. Further symptoms include losing interest in doing things, a reduction in libido, a lack of energy and finding it difficult to concentrate. Some people start over-thinking things, feeling guilty or even begin to wish they were dead.

While we have all experienced feeling low at some point in our lives, a distinct feature of depression is how long these symptoms continue for and how bad they can become. They are often experienced as unremitting.

The depressed brain

We have been studying the brain regions affected by depression for some time. For example, we have already identified widespread reductions in brain tissue known as grey matter in the limbic lobe (supporting functions including emotion, behaviour and motivation) and prefrontal regions (involved in planning complex cognitive behaviour and decision making) in depressed people.

Most previous research has looked at overall differences between groups of people with depression and groups of healthy volunteers. We did something different. We identified the pattern of brain regions that is most commonly found in our group of patients with depression. We then asked whether the same pattern could be found in another person and whether it would indicate that they were also suffering from depression.

To do this, we applied a form of analysis called machine learning, using algorithms developed from statistical learning theory and artificial intelligence. It works by recognising patterns in data and learning from these patterns to make predictions about new data sets. The data came from structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans (which use strong magnetic fields to map the location of water and fat in the body) in 23 adults with major depressive disorder and 20 matched healthy individuals.

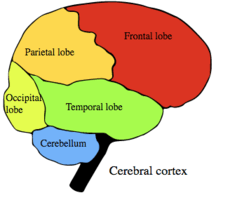

We found that there is a widespread network of brain regions which includes specific density variations in both grey and white matter in patients with depression. These extend from the prefrontal areas of the brain to the parietal lobes (which integrate sensory information), and include occipital (involved in visual processing) and cerebellar (centre for motor control) regions. We were able to match the exact same pattern of brain regions in other people who were also experiencing depression.

The study, published in the British Journal of Psychiatry, tells us that there is an underlying brain structure in depression and that we may be able to use this information to help us to make a diagnosis.

We also looked at whether we could use the same pattern of regions in individuals with different ethnicity. This is because there is some evidence that people with different ethnicity can demonstrate distinct neural responses in particular situations. But we found that the same pattern of regions appears to underlie depression in individuals with different ethnic backgrounds – adding further hope that we have indeed found a true biological marker for depression.

We also looked at whether we could predict if someone’s depression would respond to an antidepressant medication or to a talking therapy. Although we have guidelines about how to start particular therapies, we are not able to say, for a specific patient, how likely it is that the therapy will help their depression. But we found that there are specific patterns of brain regions which distinguish how well someone’s depression will improve when treated with antidepressant medication or with a talking therapy.

The pattern of regions that indicated whether a patient would experience a good response to pharmacological treatment included a greater density of grey matter in the areas that, among other things, help link behavioural outcomes to motivation. However, participants who were at risk of having symptoms that resisted treatment with medication instead would have a greater grey matter density in areas of the brain involved in evaluating reward. Based on this pattern, we were able to say that there was at least an 80 per cent likelihood that a certain patient would respond to antidepressant medication, and in some cases even higher.

The scan itself took about 10 minutes. Although promising, MRI scanners are currently not widely available, and not everyone can have an MRI scan – for example, those fitted with a pacemaker. In order for this to be used in day-to-day clinical care, we would also need to distinguish the pattern of brain regions that is specific for depression from other disorders, such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, which could show distinct networks of brain regions.

But the good news is that the study is supported by other research which has similarly found that structural MRI scans could be diagnostic for depression. The next step is to replicate and generalise these specific findings.

, Professor of Affective Neuroscience, University of East London. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks