25 years of science news: Charting the breakthroughs from the discovery of DNA to IVF embryo research

Steve Connor has been Science Editor since the launch of the IoS - he reflects on the big issues

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was the beginning of a new decade, and the birth of a new Sunday newspaper. We had decided to make science one of our main areas of specialist interest. As we look back more than a quarter of a century, many of the science-related stories we covered during that first year of The Independent on Sunday’s existence still have resonance today – whether it concerns human genetics and IVF embryo research or fears over the “dual use” of science for civil and military purposes.

During 1990 we attempted to document the onward march of scientific progress, denoted by “breakthroughs” in everything from DNA fingerprinting technology, which allowed the police to identify criminals from a single hair shaft, to fresh insights into the origins of the universe.

If journalism is the first draft of history, then we can perhaps be forgiven for overlooking the importance of some of the scientific achievements that were to make their mark in the coming decades. However, there were still many topics we covered that have turned out to have long-lasting implications for science and society.

The first Gulf War was still a year away, but Saddam Hussein’s apparent attempts to acquire weapons of mass destruction occupied many column inches. Iraqi nationals had been caught trying to smuggle small electronic devices known as krytons through Heathrow airport.

Krytons are super-fast triggers for switching high-voltage currents and are used in a range of innocuous scientific applications. As we revealed, they were to be found lying around many a university laboratory. However, they can also be used to detonate the conventional explosive charge of a nuclear bomb, which is what Iraq was thought to be interested in.

A few weeks later, the media’s attention focused on Iraq’s apparent attempts to build a supergun, a massive artillery device that could fire munitions – possibly including nuclear devices – over many hundreds of miles. It was thought to be a neat way around the military problem of delivering an atomic weapon when your air force or missile systems were not up to scratch.

Scientists were called in to advise on whether pipes made in a Sheffield steel plant and destined for Iraq could have the dual function of delivering oil as well as artillery. It was not such a daft question. A year earlier, a freelance artillery “genius” called Gerald Bull had been assassinated in Paris, almost certainly because of his role in advising Middle East states on the use of giant superguns.

Bubbling away in the background was a health scare in the making. Cows up and down the country were going wobbly at the knees before keeling over and dying. The press called it “mad cow” disease, while scientists preferred the official name of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE).

That year, government ministers went into overdrive in their attempt to reassure the public. Perhaps the most memorable photo opportunity was that of John Selwyn Gummer, the then agriculture minister, attempting to feed a hamburger to his reluctant four-year-old daughter, Cordelia.

“British beef can continue to be eaten safely by everyone, adults and children,” Mr Gummer later told the House of Commons while criticising the “alarmist reporting” by newspapers for highlighting concerns about the spread of BSE to humans.

But in the same year, other things happened that should have raised alarm bells. A cat called Max developed something remarkably similar to BSE and calves had apparently been infected with BSE from their mothers. Six years later, government ministers had to perform one of the biggest U-turns in political history by admitting that BSE can indeed be transmitted from cows to humans by eating infected beef products. It became one of the decade’s defining public-health scandals, where politicians made unqualified statements about there being “no risk to health”.

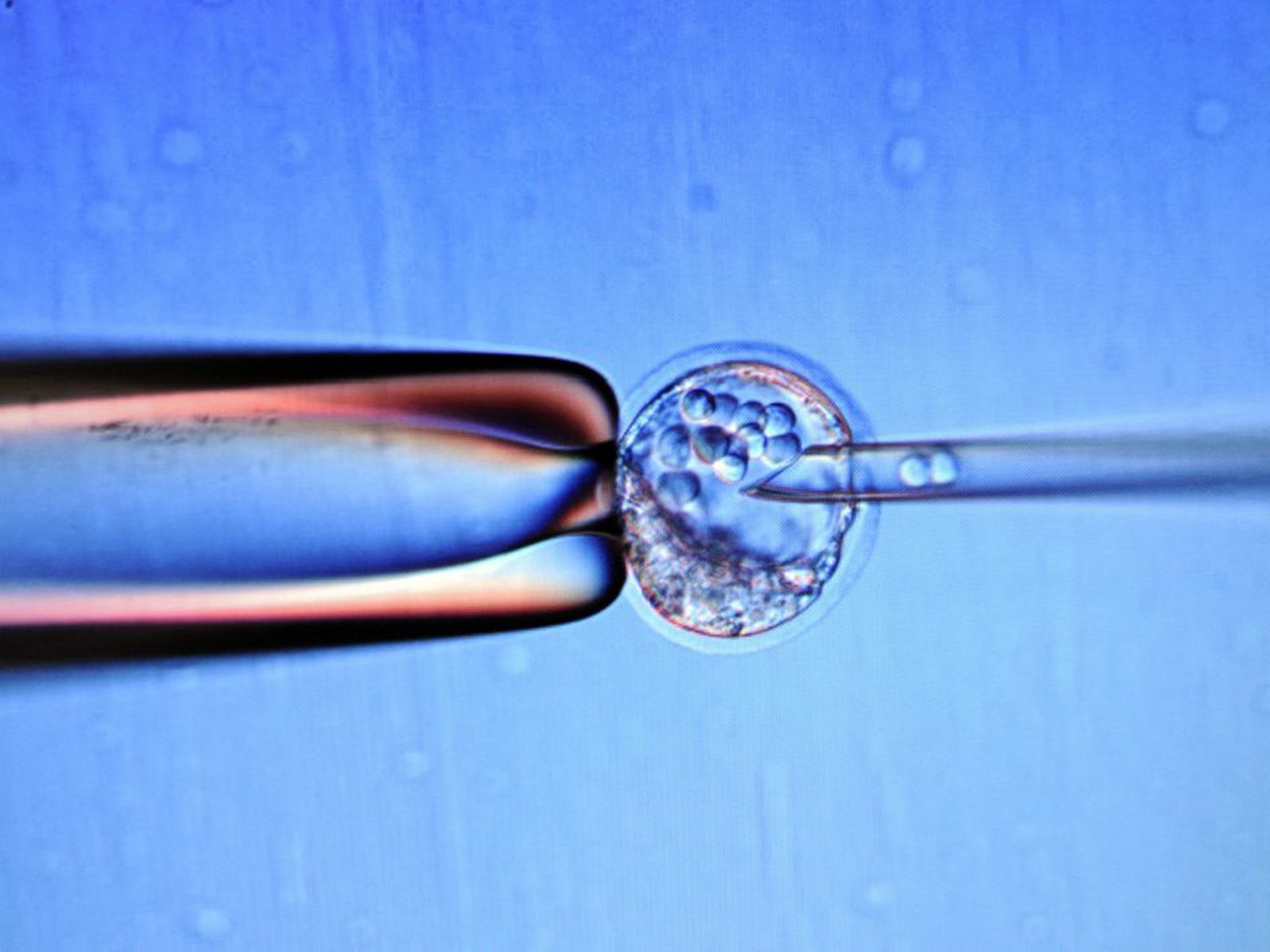

Meanwhile, the Human Embryology Bill was working its way through Parliament. Ever since the Warnock report of the previous decade, scientists had been a central part of the debate over the new technology of in vitro fertilisation (IVF). The Bill would put Britain ahead of the world by enshrining in law the legal right for scientists to research on IVF embryos up to 14 days old.

Advisers had recommended a 14-day time limit because this was before the appearance in human embryological development of something called the “primitive streak” – the first unambiguous tissue in an early embryo.

The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990 was a pioneering piece of legislation in many ways, which would control the new IVF fertility techniques through properly licensed clinics. However, developments in science soon meant that the legal framework became hopelessly out of date. The Act underwent a major revision in 2008 to allow, among other things, the creation of human-animal hybrid embryos for research purposes– something that would have been considered science fiction just 20 years earlier.

There were other serious issues involving science that were to loom much larger in the public consciousness. The most notable perhaps was a little-known problem known as global warming. It burst on to the political scene in 1990 when Margaret Thatcher delivered a remarkable speech on the wider significance of climate change. We were probably the first newspaper to highlight the scientific unknowns in temperature projections – called positive feedbacks – when a rise in temperature can in itself lead to change in the climate system that causes further temperature increases.

Not everything was doom and gloom back in 1990. Batsmen in county cricket matches were scoring record runs. Many experts – including the IoS's cricket-mad news editor, Peter Wilby – thought it might have something to do with the new balls introduced that year by the Test and County Cricket Board. The board hoped that the lowering of the ball’s seam height would redress the balance between batsmen and bowlers. But some thought the board had gone too far and brought in scientists to prove their point. In the event, everyone had to agree that swing bowling relied on factors other than seam height, such as how much beer a batsman had drunk the night before, and was ultimately beyond scientific analysis.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments