Can Obama match Abe Lincoln's gold standard?

Most inauguration speeches are dross. But a few inspire and unite the nation – and today America expects nothing less of its 44th president

Young Malia Obama at least is not getting carried away. "First African American president – it better be good," was the 10-year-old's wise comment about the address her father will deliver immediately after being sworn in to office at noon today. She picked the right spot too, during a family visit last week to the Lincoln Memorial, at the opposite end of the Washington Mall from the Capitol where Barack Obama will speak.

Abraham Lincoln is the patron saint of this inauguration, like Obama a man from Illinois, the president who liberated the slaves to whose race the soon-to-be 44th president belongs. But the setting for Malia's remark was as least as intimidating as it was inspirational. Engraved on the Memorial's inner wall, alongside the brooding statue of the great man, is his second inaugural address – 703 words long – and the gold standard against which the addresses of every President are now judged, and invariably found wanting. But if ever America needed one to match it, is is now.

This is surely the most keenly awaited inaugural speech in modern US history, perhaps ever. It will be delivered by a man renowned for his exceptional eloquence, at a moment when not just America but the world is looking for a giant pick-me-up, in the depths of the biggest economic crisis in 80 years. Its global audience probably will run into the billions, hanging on its every word.

Oddly, it is nowhere written in the constitution that an incoming president must make such a speech. But in 1789, after he became the first president to be sworn into office, George Washington decided he'd better deliver one anyway – and like most things decided by Washington it became a precedent set in stone.

In fact, those early inaugurals were above all designed to be read. They would set out the beliefs and broad political intentions of a president, and his generally ponderous reflections on the age. Only when it could not be avoided – such as with Lincoln's addresses, both overshadowed by the Civil War – did they address specific issues in detail. To this day, most of them haven't been very good, and almost none have changed history. However irrationally, this time people are expecting both from Barack Obama.

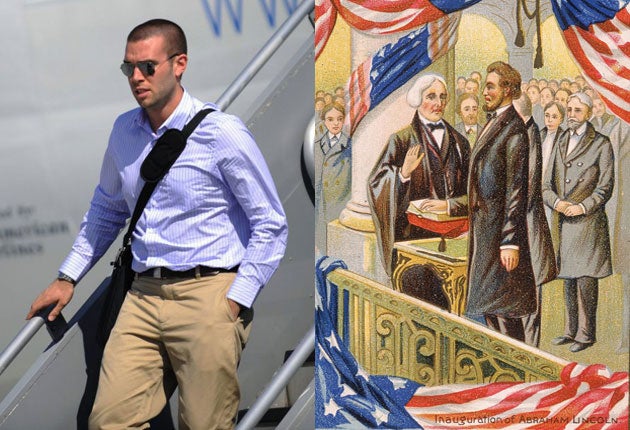

Obama's team of speechwriters, led by 27-year-old Jon Favreau, has been working on the address for more than a month. David Axelrod, Obama's chief political adviser, has been closely involved too, along with, obviously, the soon-to-be 44th president himself. It has gone through at least three drafts since Favreau began the process, jotting down ideas at his flat, and in sessions at a downtown Starbucks.

The speech will last 15 to 20 minutes, and is likely to dwell on such themes as responsibility and the country's need to return to its founding values. It will pull no punches either. "If you play it straight with them, if you explain to them ... then I have enormous confidence that the American people will rise to the challenge," Obama said in a recent interview.

There will be less of the sermonising about liberty in which George Bush indulged. In all likelihood, there will be echoes of the speech that turned Obama into a national figure: his keynote address at the 2004 Democratic convention, in which he extolled the country's diversity, but stressed that for all their differences Americans are a single people with a shared purpose.

Appeals to unity have been a stock ingredient of inaugurals: the first President Bush spoke of the "age of the offered hand," and in his second inaugural in 1997, Bill Clinton vowed that the White House and Congress should be "repairers of the breach". But these urgings had little effect. This time however is different, and Americans are in the mood to listen.

A 15-minute speech would be about par for the recent inaugural course. Predictably in a nation besotted by statistics, even inaugurals have been distilled to mere numbers. The average length of all 56 of them is 2,630 words, but of late they've been shorter, at between 1,500 and 2,000 words. The longest was that of William Henry Harrison, at 8,445 words. The shortest was George Washington's second in 1793, consisting of just 135 words. In his lone inaugural in 1797, John Adams, the second president, produced a single sentence of a mindboggling 737 words.

Warren Harding in 1921 was the first president to deliver his speech through loudspeakers. Calvin Coolidge's address in 1925 was the first broadcast by radio. That of Harry Truman in 1949 was the first to be televised, while Bill Clinton's second address in 1997 was the first to go out on the internet. A President's first inaugural address tends to be better than his second one – with Lincoln's second in 1865 being the exception. Brevity helps too; as Richard Nixon observed, "only the short ones are remembered".

Mostly, alas, they are dross. At the moment of delivery, an inaugural might sound like a text brought from the mountain by Moses in person. A quarter of an hour later, though, it is usually hard to remember a word of them.

But every so often there's a line that, for better or worse, catches the spirit of an era. "Government is not the solution to our problems," declared Ronald Reagan in 1981, at the first inaugural ceremony to be held on the west front of the Capitol, looking down over the Mall and the heart of the imperial city. Before, they took place on the building's east side, facing towards the Supreme Court. A similar moment came in 2005, when George Bush proclaimed America's "ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our time".

Today, government is looking like the only solution to the financial crisis, while Bush has bequeathed to posterity unfinished wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and a world in which tyranny if anything is once again on the advance. The younger Bush's second effort may go down as the apogee of the hubristic inaugurals, in which America asserted it had the power, the right and the moral standing to make anything come to pass. It's a fair bet that some of Obama's words will live in history – but for very different reasons. Every incoming president studies the addresses of his predecessors, and three of them may influence Obama. In 1933, Franklin Roosevelt took power amid an economic slump even deeper than today's. In 1961, John Kennedy, like Obama, was young, charismatic and consciously turning a page in American history. Finally there's Abraham Lincoln, who became president as the country descended into civil war.

By no coincidence these three produced lines that echo down the ages. "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself," said FDR, while Kennedy unforgettably demanded of his countrymen that they "ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country". None, however, surpasses Lincoln's second inaugural in 1865, delivered a month before he was assassinated.

"With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in," begins its peroration, in the rhythmic, haunting succintness that marked Lincoln as an orator. Afterwards, the Spectator magazine called the speech "the noblest political document known to history".

But these are the exceptions. In general, inaugurals have amounted to a little more than a collection of platitudes, wrapped in pseudo-ecclesiastical language. In 1993, Bill Clinton talked about celebrating "the mystery of American renewal," while born-again George Bush in 2001 made religion explicit: "We are not this story's author, who fills time and eternity with his purpose."

In other ways too, standards have been slipping. A study which measures inaugurals as reading aptitude tests, most were at university reading level until 1900. Now they are usually at high school level – or, in the case of George Bush Snr's one effort, barely sixth-grade, ie, suitable for the average 12-year-old.

There's nothing wrong with being accessible, of course. But Bush Senior turned simplicity into fatuity. "This is a time," he told his country in 1989, "when the future seems a door you can walk right through into a room called tomorrow". Deeper words than these have won the Eurovision Song Contest. Richard Nixon wasn't far behind either, with his 1969 observation that" the American Dream does not come to those who fall asleep".

To be fair, a lousy address doesn't necessarily portend a lousy presidency, nor does a soaring one guarantee a great presidency. Both speeches of Clinton, a generally successful president, sounded oddly flat. On the other hand, apart from that line about the American Dream, Nixon's two still read quite well. But it was he who 18 months after his second inaugural, resigned in disgrace over Watergate. But Harrison's fate was far worse, and far quicker. Back in 1841 Harrison spoke for an hour-and-three-quarters without a coat, on a cold, wet day. The next day he developed a cold which turned into pneumonia. A month later he was dead.

Words of wisdom: Lincoln's inauguration speech

"Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said 'the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether'. With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks