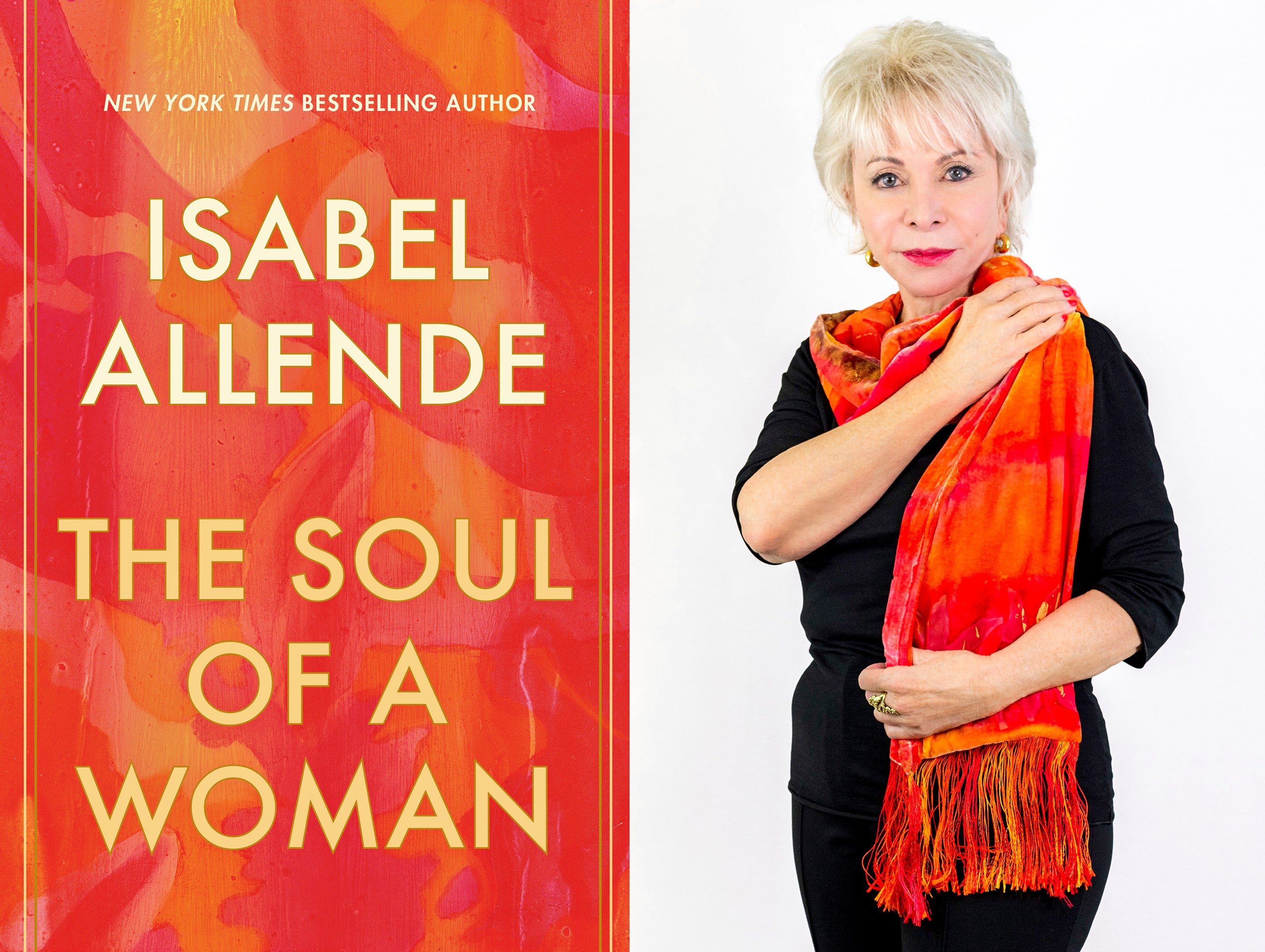

Q&A: Isabel Allende on feminism, TV series, love in pandemic

Isabel Allende is not only the most widely read living Spanish-language writer but also a self-declared and outspoken feminist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Isabel Allende is not only the world’s most widely read Spanish-language author but also a self-declared and outspoken feminist. So it is not surprising that her most recent book, “The Soul of a Woman,” arrived in the United States during Women’s History Month, just days before the premiere of a miniseries about her life on HBO Max

In her first nonfiction book in more than a decade, the Chilean author reviews her relationship with feminism from her childhood to the present, remembering those who marked her — from her mother, Panchita, and her daughter Paula to literary agent Carmen Balcells and authors Virginia Woolf and Margaret Atwood. She also reflects on the #MeToo movement, the recent social unrest in Chile and the global pandemic.

“The year of the pandemic has paralyzed everything, and much of what women had done was going out to the streets to gather and protest,” said Allende in a recent interview with The Associated Press via Zoom from her home in California. “Women alone are very vulnerable, women together are invincible... It's not that I think that it has regressed or stopped. This is moving forward.”

The first 50 years of her life are dramatized in “Isabel: The Intimate Story of the Writer Isabel Allende,” a three-part biopic premiering Friday on HBO Max and starring Chilean actress Daniela Ramírez.

Produced by Megamedia Chile and directed by Rodrigo Bazaes, the miniseries bookends the story with the death of her daughter, who died in 1992 at 29 while in a deep coma due to a porphyria crisis (as Allende wrote in her 1994 memoir “Paula”).

“It made me sob because it starts with Paula in the hospital and ends with Paula’s death. We saw it with my son (Nicolás) and we both had to stop because we were crying so hard with the first scene. But then it gets better in the sense that it is no longer so emotional for us," she said, adding that she was extremely pleased and impressed with the result.

Allende starts a new book every January 8th. Last year, the confinement allowed her to finish not one but two: “The Soul of a Woman,” a Ballantine Books release, and an upcoming novel titled “Violeta” that begins with the 1918 pandemic (“which really began in Chile in 1920,” she points out) and ends with the current pandemic. “It is the life of a woman during that time,” she says.

During the interview, Allende recalled her beginnings as a feminist and also spoke about her experience as a 78-year-old “newlywed” in confinement. She married her third husband, New York lawyer Roger Cukras, in July 2019.

Answers have been edited for brevity and clarity.

AP: You have said that you were bothered by injustices against women from an early age and that it was something you got to see in your own family. But when and how did you realize that you were a feminist?

Allende: Darling, there was no such a word back then! When I was a girl in Chile in the 40s, in a conservative, Catholic, patriarchal family, my mother had been abandoned by her husband and we lived in my grandfather’s house. All men, my uncles and my grandfather. And my grandfather was the absolute patriarch. He was a very good man, I adored him, but he was the highest authority, he was like God. What my grandfather said was not questioned. I grew up with the feeling that my mother was in a situation of injustice, in a situation of inequality, of vulnerability. My mother lived in the same house and I suppose my grandfather paid for school and all that, but my mother never had money, she never had freedom. Being a separated woman at that time, in that society, my mother was very frowned upon; she had to take great care of her reputation, for which she was also very limited. And when did I come to realize that this anger that I felt had a name? It was not, I think, until adolescence, because there were no references. And I couldn’t realize that there really was a movement, and that I could belong to that movement, until I was 20 at least.

AP: And did you feel liberated or accompanied in any way? How do you remember it?

Allende: I remember when I read “The Female Eunuch” (1970) by Germaine Greer, which was a book with humor, with intelligence, with a way of saying things that was so direct and so obvious. I was feeling all those feelings, but I had not expressed them, I did not know how to articulate them, until I read that book.

AP: “The Soul of a Woman” is your first nonfiction book in more than a decade. What led you to write it now?

Allende: It wasn’t my idea. I gave a speech in Mexico City a while ago and the speech was a viral phenomenon. The publishers in Spain thought they were going to publish it as a little book. I read it and said, “This thing is totally outdated,” because in a short time #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, the protests of women in the street... so much had happened that was not mentioned in the speech. I said, “No, this is useless.” Then I started to think about my own trajectory and how I have lived the movement, because it has been almost simultaneous, you see? The women’s liberation movement is very old, but it really began with the pill in the 1960s, when women were able to control their fertility for the first time. That created a space that didn't exist before, a space that my mother of course did not have — my mother was married for four years and had three children.

AP: You started writing it just as we were starting to lock ourselves up because of the pandemic. What do you hope will happen now with the women’s movement?

Allende: The year of the pandemic has had everything paralyzed, but things continue to move forward. And feminism has joined other movements that are also on the streets, like Black Lives Matter, which is a subversion against the establishment, against a racist system. That same system, a chauvinist system, is what gives the male gender supremacy over other women, over other races, over people who have no power, over children. When we challenge the power of the establishment, we have so much in common that we can do it together. We have arrived to a moment were we must shake up the society we live in and try to establish a different, more sustainable, more just and better new normal for ourselves, for everybody.

AP: How has the pandemic treated you?

Allende: Well, because what a writer needs is time, silence and solitude, and the pandemic has given me that. I’m a newlywed and look, the pandemic has been a litmus test because it's like a long honeymoon that never ends (laughs). But in this honeymoon we have learned a lot as a couple, as a family, that can be extrapolated to humanity: We are forced to live on a fragile planet, in a limited space that has to be sustainable, that we have to keep in order and clean, otherwise we will perish. That we need patience, tolerance, compassion, kindness. We need enough resources for everyone.

AP: How do you feel about the biopic on your life? Have you seen it?

Allende: When they told me about the project, I never thought they were going to do it, so I didn’t give it much attention. One day they called me and the thing was practically done. The only thing I asked of them is to respect the other people who appear in the series, because look, I have written memories about my own life, I've been a bit of a chatterbox so I don't have the right to claim privacy. But the people around me who have private lives, you have to be respectful with them; those stories don’t belong to me. But they (the producers) did a good job, because they respected my ex-husband, my children. I really liked the end result.

AP: What did you think of the leading actress? Did you feel well represented?

Allende: Daniela Ramírez plays a role that I think it’s very difficult to do, to imitate another person, to try to be the other person. And furthermore we don't look alike; she is a very young and beautiful woman. But look, they even did the hairstyles, the dresses. I have a necklace with silver coins and each of those coins is different, a jeweler made especially for me. They made it identical! And like that, many details — what the house was like, the children ... It is truly thrilling.

___

Follow Sigal Ratner-Arias on Twitter at https://twitter.com/sigalratner.