Public service in the US: Increasingly thankless, exhausting

Historically, public service jobs have given people a chance to give back to their communities while earning solid benefits, maybe even a pension

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

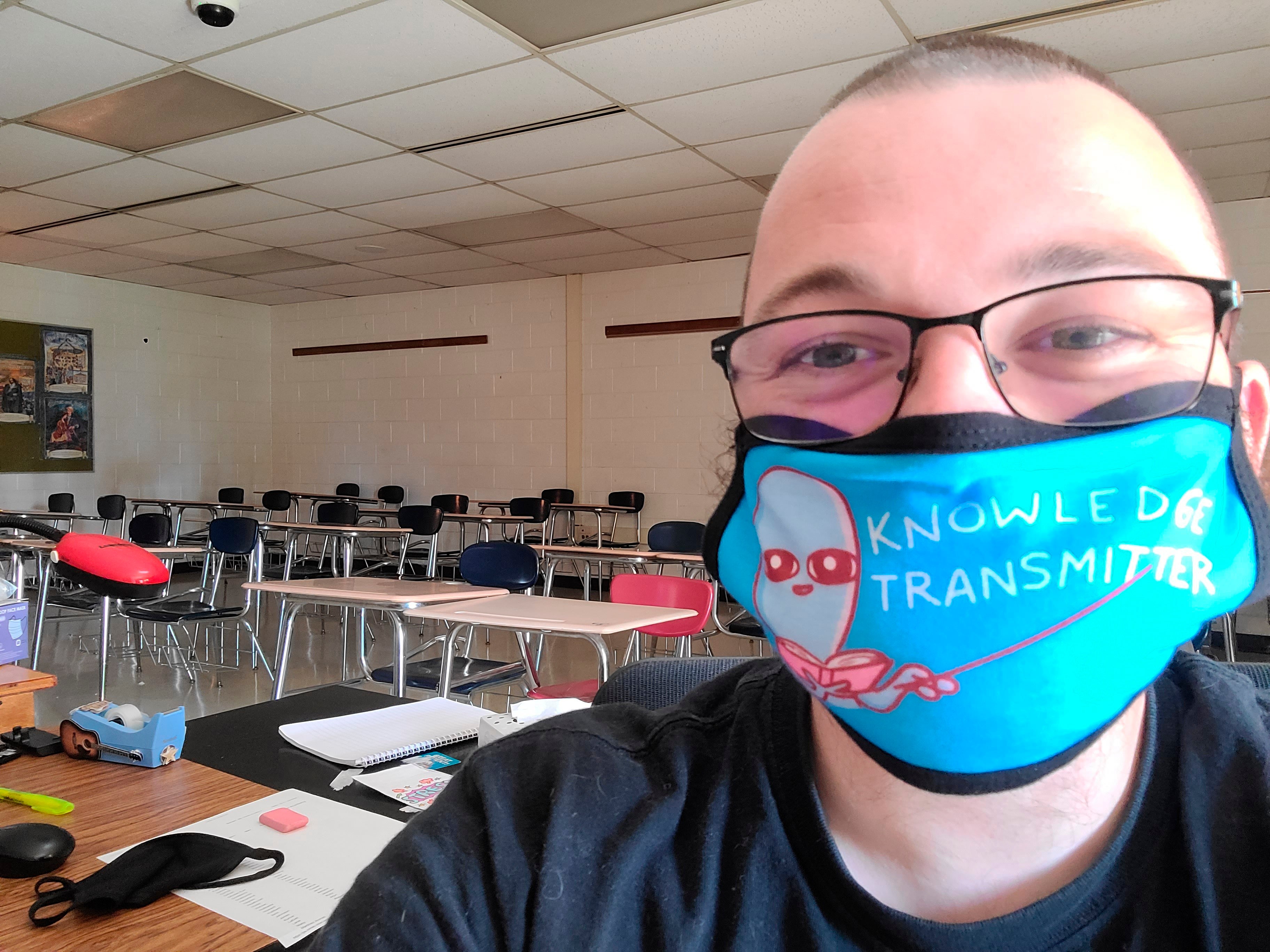

Your support makes all the difference.Teaching high school was Bill Mathis’ dream job, the one he referenced in a childhood journal he still keeps: “I would love to be a teacher,” he scrawled in pencil as a third grader.

Now Mathis has taken a new job, in Michigan’s newly legalized cannabis industry. The pay is better, the hours more regular, the stress less, he says. No longer does he worry that he’ll catch COVID-19. “What about us and our families?” he asked his school board in Romeo, Michigan, last August after it unveiled a plan to offer in-person classes.

Ultimately, the 29-year-old teacher felt few in the rural suburb north of Detroit understood. “Good riddance,” one resident said.

His is but one story of the plight of the American public servant. Historically, jobs like teaching, firefighting, policing, government and social work have offered opportunities to give back to communities while earning solid benefits, maybe even a pension. Surveys still show public admiration for nurses and teachers and, after the terror attacks of 9/11, firefighters.

But many public servants no longer feel the love.

They’re battered and burnt out. They’re stretched by systems where shortages are common – for teachers in Michigan and several other states, for instance, and for police in many cities, from New York and Cincinnati to Seattle Colleagues are retiring early or resigning, as Mathis did. There are mental breakdowns, substance abuse and even suicide, especially among first responders.

Even before the coronavirus arrived, researchers have found in 2018 that about half of American public servants said they were burnt out, compared with 20% over workers overall.

Some wonder who will pick up the slack, as more young people avoid public service careers. In the federal government, just 6% of the workforce is younger than age 30, while about 45% is older than 50, according to the nonprofit Partnership for Public Service.

The pandemic has only made matters worse.

In addition to the risk COVID-19 poses for those on the front lines, “The workload is up. Financial security is down,” said Elizabeth Linos, a behavioral scientist and public management scholar at the University of California, Berkeley, who studies public workers.

Linos, whose research has included 911 operators, physician moms and others, says surveys during the pandemic have found that anxiety rates for frontline workers are 20 times higher than usual.

Long before the pandemic, mistrust of the government and its workers was building. By the time the 2008 Great Recession arrived, anti-union sentiment also was more prevalent -- a big deal in the Detroit area, known as a union stronghold because of the auto industry. That bashing has grown to include unions that represent public servants, teachers included.

“They protect bad behavior, and they punish good behavior,” said Tim Deegan, a dad from Waterford, Michigan, who manages a pizza parlor. He notes that he has no such protections for a job that often finds him working 60 hours a week.

Earlier this year, Deegan took part in a rambunctious social media discussion about the large numbers of Michigan teachers who are retiring early, even more during the pandemic. Educators certainly had their supporters in the online thread. But others, including Deegan, were angry. He told the story of his girlfriend’s son – how they’d switched him to another school district because he felt the online teaching was so poor. Some teachers, he said, have “phoned it in” for years, with few repercussions.

Bill Mathis, not one to shy from speaking his mind, jumped into the discussion. He posted about leaving teaching because of the health risks to himself and his girlfriend, Annie who has lupus, and how his salary made it hard to pay his bills.

“So you weren’t in it for the kids?” another commenter asked, drawing dozens of emoticon reactions, from anger to laughter.

Derek Lies, a dad of two boys in Romeo, said he felt for teachers -- at first. But as the union pushed back on returning to the classroom, “my sympathy went away,” he said.

Years ago, Lies was a firefighter. If there’s one group of public servants who have reason to gripe, he added, it’s police, who’ve faced heightened scrutiny over the killings of George Floyd and others.

“I can’t imagine anyone wanting that job right now,” Lies said.

Increasingly, first responders across the country are acknowledging the difficulties of the job and addressing mental health, addiction and the occasional suicide. In Sterling Heights, where Mathis lives, fire chief Kevin Edmond gives time off to crews who’ve responded to fatal fires and other trauma.

Attracting young people to public service fields can be a challenge. But Linos, the UC-Berkeley researcher, says it’s not necessarily the difficulty that scares them off.

In fact, in the case of policing, her research has found that more people apply when told the job is challenging. Her research has found that a sense of belonging and feeling supported by a supervisor also helps soothe burnout.

In Romeo, sixth-grade geography teacher and union leader Sue Ziel recalls starting to feel more resentment from the public when the recession began in 2008. A Gallup poll then found that public approval of unions dropped to a low of 48 percent, compared with 72 percent when the poll began in 1936, though it has been creeping up.

Ziel, who left a job in advertising 24 years ago to teach, said the demands of the job had increased. There are more required certifications, more focus on standardized testing, while pay freezes diminished teacher wages across the state of Michigan.

As the pandemic hit, she initially felt “paralyzed” at the thought of having to teach kids online and in person at the same time. She also got the virus.

“I remember sitting in tears and telling my husband ‘I don’t know if I can do this,’” she said, “and those words have never come out of my mouth.”

As a veteran with experience on which she could draw, Ziel pushed through. But she said younger staffers were more likely to struggle with less support in a stressful time, as Bill Mathis did.

Mathis’ departure “breaks my heart,” she said. “I really think the world of Bill.”

___

Martha Irvine, an AP national writer and visual journalist, can be reached at mirvine@ap.org or @irvineap