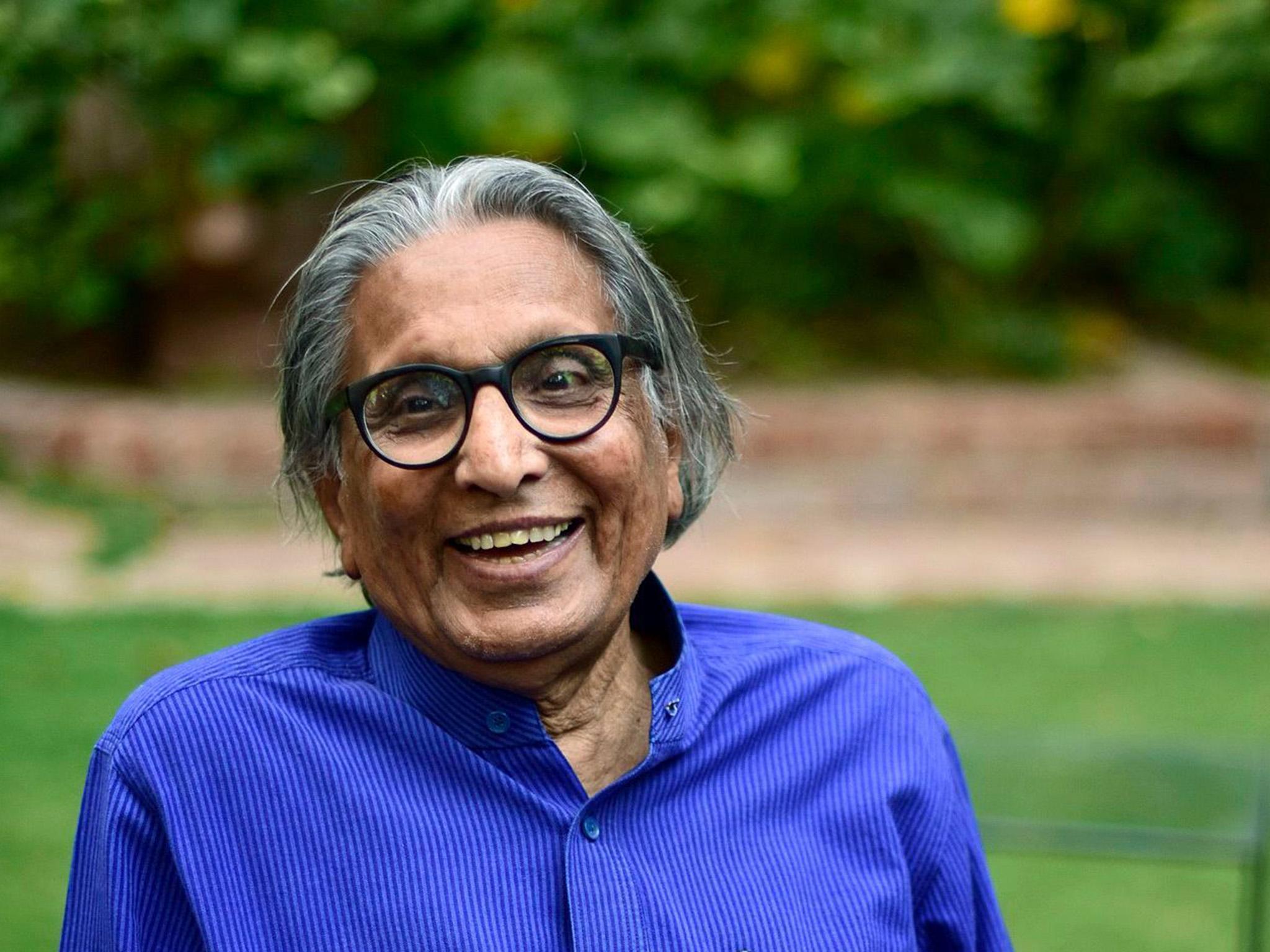

Low-cost housing pioneer wins Pritzker Prize

The Indian architect Balkrishna Doshi has clinched his industry’s greatest accolade – but his 70-year career has always been about much more than awards

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Balkrishna Vithaldas (aka BV) Doshi doesn’t talk just about his buildings. This architect, urban planner and educator talks about how his buildings aim to foster a sense of community, how space can promote inner peace, how cities can contribute to the health of a society.

Considered a pioneer of low-cost housing, Doshi, 90, is thrilled to have been awarded the 2018 Pritzker Prize, architecture’s highest honour, which was announced on Wednesday. He is the first laureate from India, and worked with the 20th-century masters Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn.

“It is a very wonderful thing that happened,” he says from his home in Ahmedabad, a city that was once the centre of the non-violent struggle for Indian independence. The award will be bestowed on Doshi, the 45th laureate, at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto in May.

But Doshi’s 70-year career has always been about much more than prizes – of which he nevertheless has many – or international renown, of which he had relatively little, given that he is not a household name.

Doshi has been consumed with larger issues like social good and sustainability. And he bemoans a culture and profession that he sees as overly concerned with the bottom line. “One is all the time looking at financial returns – that is not only what life is,” he says. “I think wellness is missing.”

What Doshi means by “wellness” are considerations like how we can “connect with silence”, how “life can be lived at your own pace” and “how do we avoid the use of an automobile”.

The architect has brought this type of philosophical thinking to projects like his Aranya Low Cost Housing near Indore (1989), where more than 80,000 low- and middle-income residents now live in homes ranging from modest one-room units to spacious houses, with shared courtyards for families.

He also designed mixed-income housing for a life insurance corporation in Ahmedabad (1973), which combines income groups on three floors of a pyramidal housing block approached through a common staircase. The Vidhyadhar Nagar Masterplan and Urban Design in Jaipur (1984) features channels for both water harvesting and distribution. (The Vidhyadhar housing plan recalled Doshi’s work with Le Corbusier in Chandigarh, with its wide central avenues, and a study of Jaipur’s Old City.)

“Housing as shelter is but one aspect of these projects,” the Pritzker jury said in its citation. “The entire planning of the community, the scale, the creation of public, semi-public and private spaces are a testament to his understanding of how cities work and the importance of the urban design.”

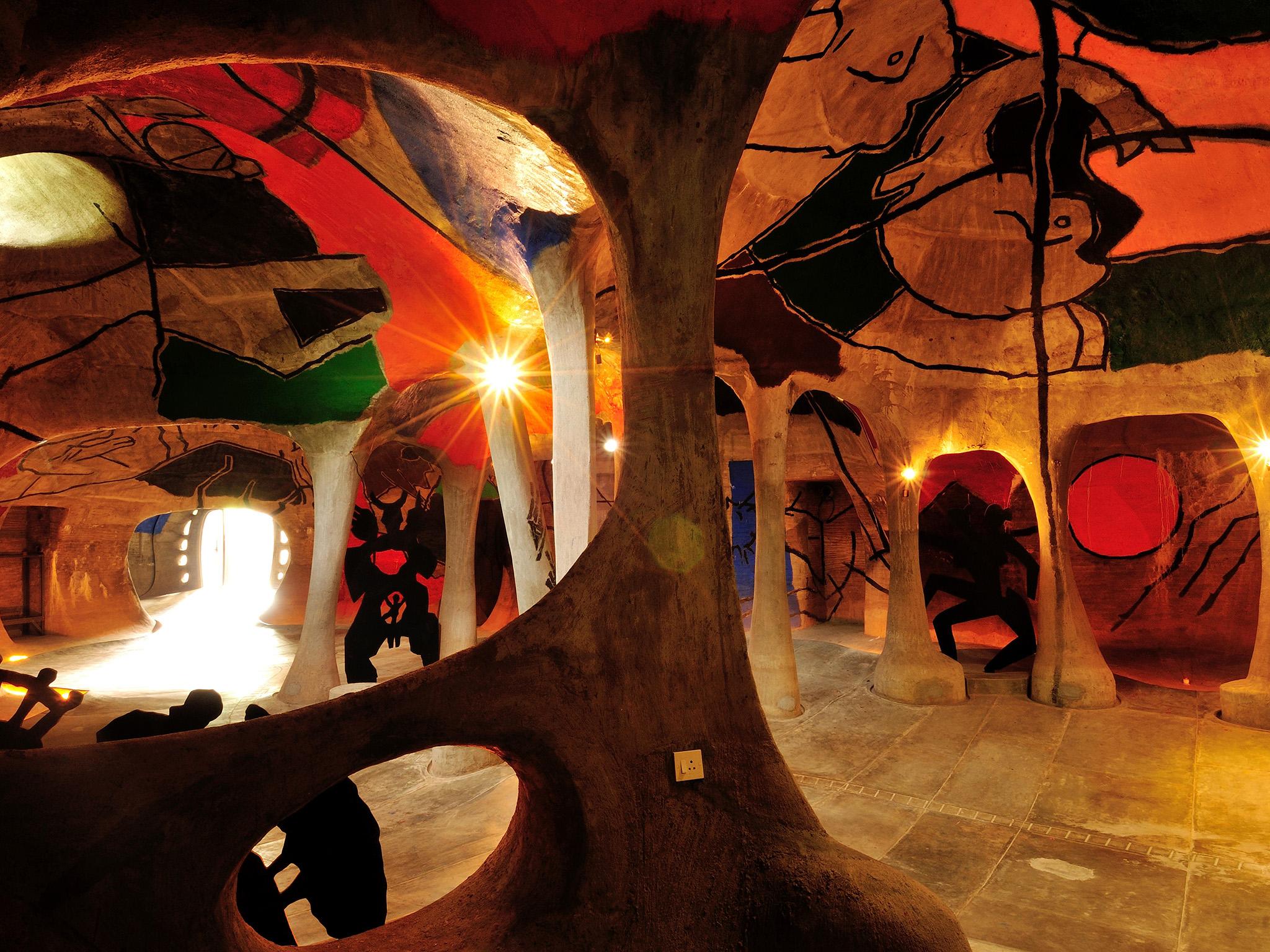

Doshi’s emphasis on communal spaces is reflected in his own work studio Sangath (roughly translated as “moving together”) which includes a garden and outdoor amphitheatre, spaces designed to foster the exchange of ideas. The mosaic tile in his studio also appears in the undulating roof of Doshi’s underground art gallery in Ahmedabad, Amdavad ni Gufa (1994), which features artwork by Maqbool Fida Husain.

Doshi describes the gallery project as “a challenge between an artist and an architect to give birth to the most unexpected”.

“Searching the uncommon meant raising fundamental questions,” he adds, “meaning of function, meaning of space, meaning of technology, structure and form.”

Education is central to Doshi’s work; he has taught and lectured all over the world. The architect says that he has founded six schools, including the School of Architecture and Planning in Ahmedabad (designed and built from 1966 to 2012). (It was renamed CEPT University in 2002, and he is dean emeritus there.)

His educational buildings include the Indian Institute of Management, Bangalore (1977 to 1992), a series of interwoven streets, courts and classrooms inspired by traditional, maze-like temple cities in southern India.

Born in Pune, India, in 1927, Doshi began his architecture studies in 1947 at the Sir JJ School of Architecture in Mumbai. He then moved to London and to Le Corbusier’s atelier in Paris, where in the 1950s he helped work on Chandigarh, the experimental Modernist city about 150 miles north of New Delhi. Doshi ultimately settled in Ahmedabad, where he helped supervise construction of Le Corbusier’s Mill Owners’ Association Building (1954) and worked on other Corbusier projects, including the Sarabhai House in Ahmedabad (1955).

In 1956, Doshi founded his own practice, Vastushilpa – now Vastushilpa Consultants – which has five partners and 60 employees.

The firm’s 100-plus projects include the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad (1962), on which Doshi worked as an associate for the architect Louis Kahn – an collaboration that lasted more than a decade.

His work is deeply evocative of Indian history and culture, drawing on the grandeur of shrines and temples, the bustle of city streets, and the local materials like those in his grandfather’s furniture workshop.

He does not set out to design an iconic structure. Rather, Doshi approaches his projects with an eye towards seeding miniature societies that residents can expand and animate over time.

“Architecture is not a static building – it’s a living organism,” he says. “How do we add on coffee shops, restaurants, bookshops so you can use the building? Can we bring life into what we create?”

“What is the role of an architect today?” Doshi adds. “Are we going to be a service provider working for a client, or are we going to be useful to the society at large?”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments