Pop-up school for US asylum seekers thrives despite pandemic

It started as a kind of pop-up school on a sidewalk to teach reading, writing and math to Central American children living in a camp of U.S. asylum seekers stuck in Mexico

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It started out simply: A pop-up school on a sidewalk to teach reading, writing, math and art to Central American children living in a camp of asylum seekers stuck at America's doorstep.

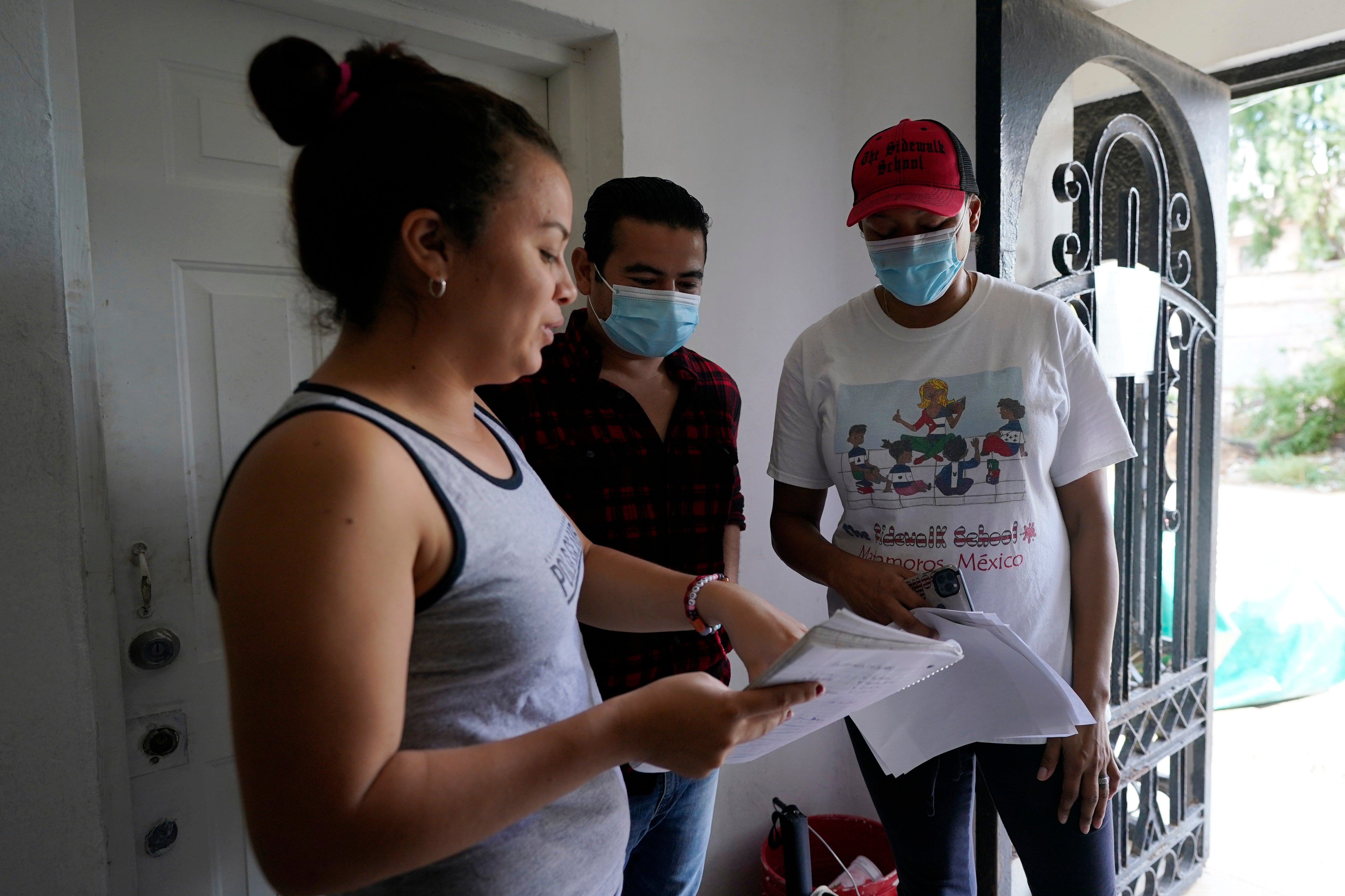

Like countless schools, the sidewalk school, as it became known, had to go to virtual learning because of the coronavirus pandemic. Instead of being hampered by the change, though, it has blossomed, hiring about 20 teachers — all asylum seekers themselves — to give classes via Zoom to Central American children in not only the camp, but at various shelters and apartments in other parts of Mexico.

To be able to switch to distance learning, the teachers and students were outfitted with more than 200 Amazon tablets by The Sidewalk School for Children Asylum Seekers. The organization was founded by Felicia Rangel-Samponaro, who lives across the border in Brownsville, Texas, and has been crossing to help the asylum seekers by providing them food and books.

Rangel-Samponaro, 44, said that to buy the tablets, she used her own money and raised funds, including through a GoFundMe campaign. She said she felt obliged to do something for the asylum seekers because the U.S. government had upended their lives.

“This is a U.S. problem," she said. “We created this. We're the ones that continue to let this go on. This falls on American citizens."

A Trump administration policy forced asylum seekers to wait south of the border as their cases proceed through U.S. courts, leaving thousands of Central American families living in tents or at Mexican shelters. Previously, asylum seekers were allowed to remain in the United States with relatives or other sponsors while their cases proceeded.

Many have spent more than a year with their lives in limbo, and the wait has only grown longer with the Trump administration suspending immigration court hearings for asylum-seekers during the pandemic.

The classes have offered children not only the chance to catch up on studies that were interrupted when their families fled violence in their homelands, but also a distraction from the long days of boredom.

On a recent Friday morning, Gabriela Fajardo held a Zoom class while sitting on an overturned bucket in a hallway of a small apartment building full of asylum seekers who have found enough work to be able to afford to move out of the camp in Matamoros. Interacting with her on her screen were several Central American children living in the Mexican border city of Ciudad Juarez, about 830 miles (1,335 kilometers) to the west along the Texas border.

“Remember, hello is hola," she said in Spanish to a student named Jeremy, enunciating her words carefully as she leaned into her tablet set on a wooden table. “Good morning is buenos dias. You have to speak in English over there or no one is going to understand you in Spanish except your mother."

“That's why I'm sharing with you the little I know," said the 26-year-old Honduran woman, who is stuck in Mexico like her students.

The boy gave an enthusiastic response: “OK, then in English! I have to speak in English," though he was still speaking in Spanish.

Fajardo let out a big laugh and proceeded with the lesson.

Fajardo, a primary school teacher, fled from her village with her son after they received threats because her brother is a police officer. She has already spent a year and four months in Mexico as her case slowly proceeds through the U.S. courts.

Being able to teach — her life's passion — has given her a sense of purpose. She said it makes her angry to see children miss out on their education.

“I’ve noticed children who are older and know nothing," she said. “A child needs to start learning from the age of six to read and do math.”

Fajardo left her country so that her son could have a better life.

But as they wait in this crime-ridden border city, she is grateful to be able to provide an education to so many other children whose futures are also uncertain.

“I was taught in college that the reason to get an education is to be able to educate others," Fajardo said. “That's what inspires me.”

____

Associated Press video journalist John Mone contributed to this report.