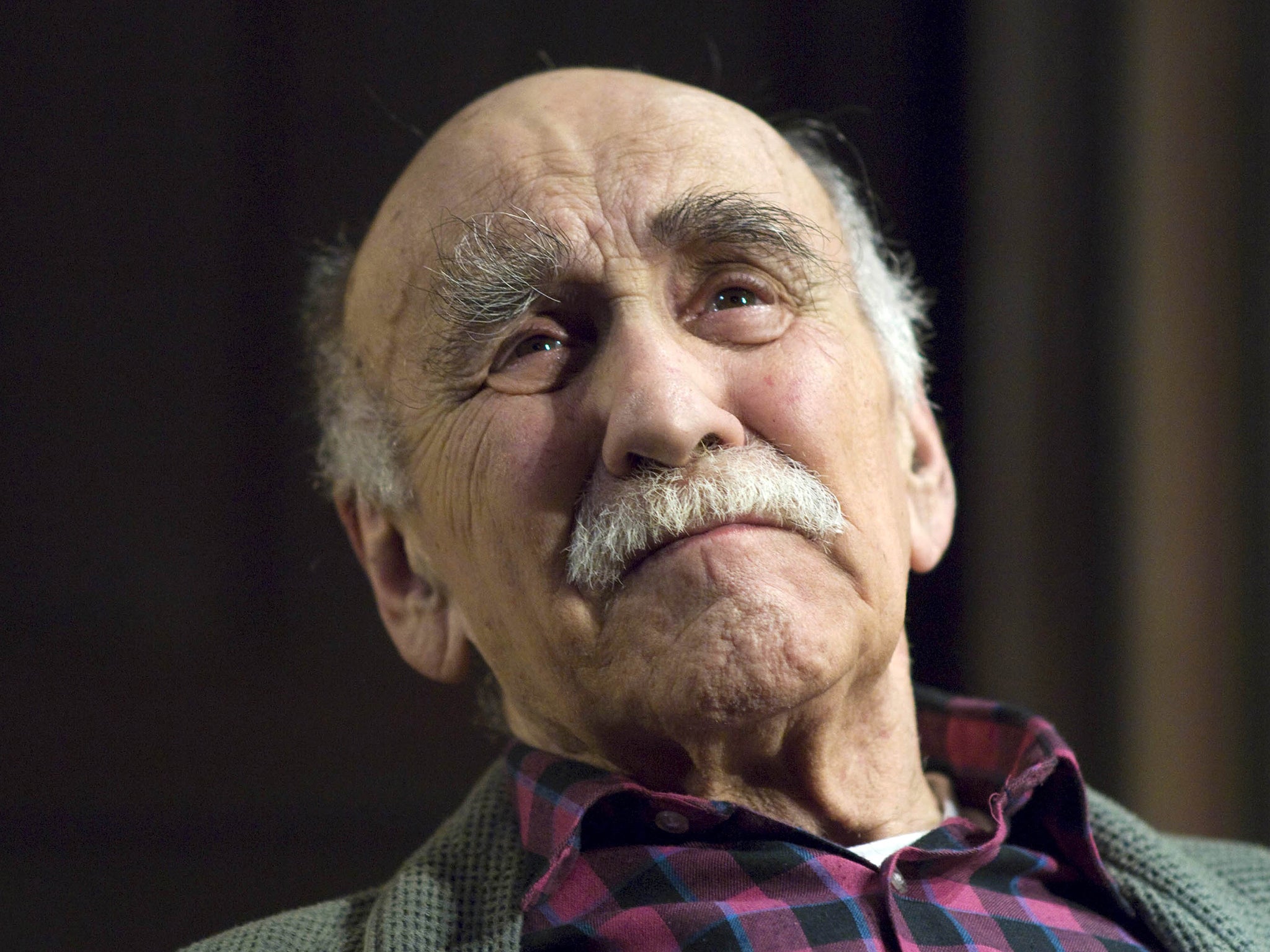

Warren Mitchell: Actor best known as Alf Garnett in Till Death Us Do Part

His reputation was for that of a fiery and funny man

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Warren Mitchell first came to public attention when, aged almost 40, he took the role of the racist bigot, Alf Garnett, in the Johnny Speight comedy Till Death Us Do Part. Between 1965 and 1975, 20m people would tune in to watch what had become a national institution. Mitchell made the part his own, but at the same time, never quite escaped it.

Warren Misell – he later changed his named to Mitchell – was born in 1926 in the East End of London. His paternal grandparents came from a line of English Jews traceable back to the Restoration. His maternal grandparents were Russian immigrants who came to Britain in 1910 and opened a chip shop in Stoke Newington. Mitchell’s father, Monty, was a china and glass merchant.

One of Mitchell’s earliest memories is of coming home from Canterbury Road School in Leyton, aged five, and excitedly telling his orthodox Jewish grandmother that he was to be Tiny Tim in A Christmas Carol, a part which would require him to eat real Christmas pudding. His parents refused to allow him to take the role because Christmas pudding contains suet, forbidden by Jewish dietary laws.

When he was 14, Warren was chosen to play football for Southgate School’s First XI – a long-held dream. But again, his family’s orthodoxy frustrated him. The match was on Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar. He told his father he would not be going to synagogue, and was sent to his room. He escaped, however, and went to the match. “We were three goals up by half time,” he later recounted, “and I thought, ‘So, where’s the thunderbolt?’”

Mitchell’s talent for entertainment had showed early. On holiday at Clacton, he and his older sister, Betty, went in for an end-of-the-pier competition run by a clown. Mitchell danced and sang songs, one of which was “Nobody Loves a Fairy When She’s Forty”. After they had won several times, the clown had to ask the pair not to enter again.

Mitchell’s mother, Annie, died when he was 15, but he managed to do well at school, despite also being by his own admission “a pretty naughty boy..” He did “matric”, the equivalent of “O” levels, in nine subjects and went on to study pure maths, applied maths, physics and chemistry. He claimed never to have read a book until he joined the RAF. Although the teachers would tell him he would never get anywhere, Warren would come top in his year. His headmaster once said that although he ought to congratulate someone of Warren’s achievements, he couldn’t because of the small matter of his 31 detentions that term.

Mitchell went to University College, Oxford as a member of the University Air Squadron, before joining the RAF as a navigator, alternating lectures in physical chemistry with sessions of flying. He also ran, swam and boxed. At Oxford, he met Richard Burton and they joined the RAF proper together. It was Burton’s influence that persuaded Mitchell to join Rada in 1947; the RAF had paid before his demob for Mitchell’s Rada entrance tuition.

He studied at Rada for two years “learning posh”, as he put it, and spent his evenings unlearning posh by playing at the left-wing Unity Theatre. His first professional performance was in 1950 at Finsbury Park Open Air Theatre. Although not a well-known actor as a young man, he was made an early living on TV, specialising at playing foreigners – he excelled at the accents – in shows like The Avengers, The Saint and Danger Man.

Mitchell met and married a fellow actor, Connie Wake, in 1952, with a wedding ring hired from a pawn shop. Their wedding breakfast was a 2s 3d meal for two in a cafe in King’s Cross. For the first two years of their marriage, Mitchell’s father refused to meet Connie because she wasn’t Jewish. Eventually, by the time the couple had their children, Rebecca, Danny and Anna, the rift had been healed, although Mitchell said that even for the first 30 years of their marriage his father thought it still might not last. They celebrated their golden wedding anniversary in April 2001.

When the BBC was developing Till Death Us Do Part, which began life as a one-off play for Comedy Playhouse, Mitchell was not their first choice for the Alf Garnett role; Peter Sellers, Leo McKern and Lionel Jeffries had all turned it down. Despite his strong left-wing leanings, he took on the part with extraordinary gusto, and into old age, long after Johnny Speight’s death, could instantly “do a bit of Alf” for chat shows and interviews. He won the 1966 TV Actor of the Year Award.

Although as Garnett, Mitchell would spit out lines such as “yer bleedin’ coons coming over here, taking our jobs,” and rail against the Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson (“yer bleedin’ ’Arold”) he believed that 99 per cent of viewers appreciated that you were supposed to laugh at Garnett, not with him. “Alf did a hundred times more to combat racism than all the well-meaning clergymen who ever preached against it,” he once said. “He said all the things that people weren’t supposed to talk about. All those awful things that fester in people’s souls.” However Mitchell did admit that he was ashamed that when playing in character in a live show, one of Alf’s remarks – “Adolf Hitler had his moments” – raised a cheer from part of the audience.

ITV revived the series as Till Death..., and from 1985 to 1992, the BBC produced a sequel, In Sickness and in Health. Although Mitchell was in danger of being typecast, Sir Peter Hall was of the opinion that he was “much more and much less than Alf Garnett. He is a very versatile actor.” In fact Mitchell’s triumph as Willy Loman in the National Theatre’s 1979 production of Death of A Salesman rates in Hall’s top 20 performances and won Mitchell two best actor awards for that year. The play’s author, Arthur Miller, also said Mitchell was the best Loman he had ever seen.

Mitchell was also admired for fine performances in The Caretaker, King Lear and as Shylock in The Merchant of Venice. In later years he starred in the BBC TV production of Gormenghast as Barquentine, in Visiting Mr Green at the West Yorkshire Playhouse, and in the West End play, ART. As a film actor, Mitchell had a steady stream of roles. They included parts in Diamonds Before Breakfast, Assassination Bureau, Whatever Happened to Charlie Farthing, Jabberwocky, Stand Up Virgin Soldiers, Norman Loves Rose, The Chain – and, of course, the film version of Till Death Us Do Part.

Mitchell’s fraught relationship with Judaism and Jewish culture continued. “I enjoy being Jewish,” he once said, “but I’m an atheist. I hate fundamentalism in all its forms. Jews, Catholics, Baptists, I think they’re all potty and capable of destroying the world.” The Mitchells lived in a house in Highate, North London with a swimming pool and a tennis court, bought in 1968 with the funds from the first two years of Till Death. Mitchell also invested in a Jaguar which he was still driving at the turn of the new century.

When Danny, Mitchell’s actor son, emigrated to Australia, Mitchell spent so much time visiting that he eventually became an Australian citizen. Despite having suffered from traverse myelitis, a disease of the spinal cord, and having had two hip replacements, Mitchell remained active, trying to swim or do yoga every day. He was also a keen sailor and played the clarinet. He suffered a mild stroke in 2004 but was back on stage a week later as a cantankerous old Jew in Arthur Miller’s The Price.

His reputation was for that of a fiery and funny man. His family nickname was “bully bottom’” But he was always quick to be humorous about himself, once telling an interviewer that he and his beloved Connie had had a marriage crisis over a wheelie bin. She wanted a new one and he thought the two old council dustbins were perfectly OK. Connie won in the end and the marriage, of course, survived. He said once, “I don’t think I have always been a very lovable person. I am a bit edgy, tetchy, irascible and inconsistent at times. But I have been loved by a very, very tiny handful of people.”

Mitchell once pre-wrote his own obituary for a newspaper: “Warren Mitchell struggled in the latter part of his career to discard one particular television image. He overcame typecasting and played many parts to some critical success. He is survived by his wife, children, grandchildren – and Alf Garnett.”

Warren Misell (Warren Mitchell), actor: born London 14 January 1926; married 1952 Constance Wake (two daughters, one son); died 14 November 2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments