Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Most economists believe that markets work. They believe that to a large extent, markets are efficient, self-regulating, and they produce what is best for society. The idea is seductive because it seems to excuse greed, or even celebrate it -- the alchemy of the invisible hand turning all of our selfish impulses into goodness and bounty.

Of course, there are limits to what markets can accomplish. Economists George Akerlof and Robert Shiller have each made their careers -- and won Nobel prizes -- for investigating how laissez faire fails us. Akerlof analysed the problems that arise when we don't know enough about what we're buying. Shiller showed that the stock market often moves irrationally, in ways that reflect human fallibility.

In their first book together, Animal Spirits, Akerlof and Shiller documented all the different ways that people behave emotionally, over-confidently, or naively, and demonstrated how these psychological mistakes resonate through the economy.

Their latest book, Phishing for Phools, takes the idea further. Not only are people vulnerable to making mistakes with their money, they argue, but the market is exceedingly good at exploiting them.

"The economic system is filled with trickery, and everyone needs to know that," they write in the book's opening pages.

I recently sat down with Akerlof and Shiller for an hour-and-a-half conversation to discuss their view that the market is not fundamentally a force for good. The market is amoral, they say -- it might be optimally efficient, but it will deliver woe as efficiently as it delivers happiness.

An interview with the Yale professor who was a pioneer of behavioral finance. (Brendan McDermid / Reuters) An interview with the Yale professor who was a pioneer of behavioral finance. (Brendan McDermid / Reuters)

"Markets not only have a huge upside," Akerlof told me. "They also have huge downsides."

Economics predicts that wherever there is a profit, someone will be there to make it. To that, Akerlof and Shiller propose a corollary: Wherever there is an opportunity to profit off people's weaknesses, someone will exploit it.

Gyms, for instance, make their money off rigid long-term contracts because they know people overestimate their commitment to working out. Snack food companies count on us being bad at controlling our diets. What some might regard as personal failures -- laziness, or lack of self-control -- Akerlof and Shiller see as universally human weaknesses that the market is particularly good at manipulating. At its worst, they say, this kind of manipulation leads to addiction, bankruptcy, political corruption, and diseases like diabetes and cancer.

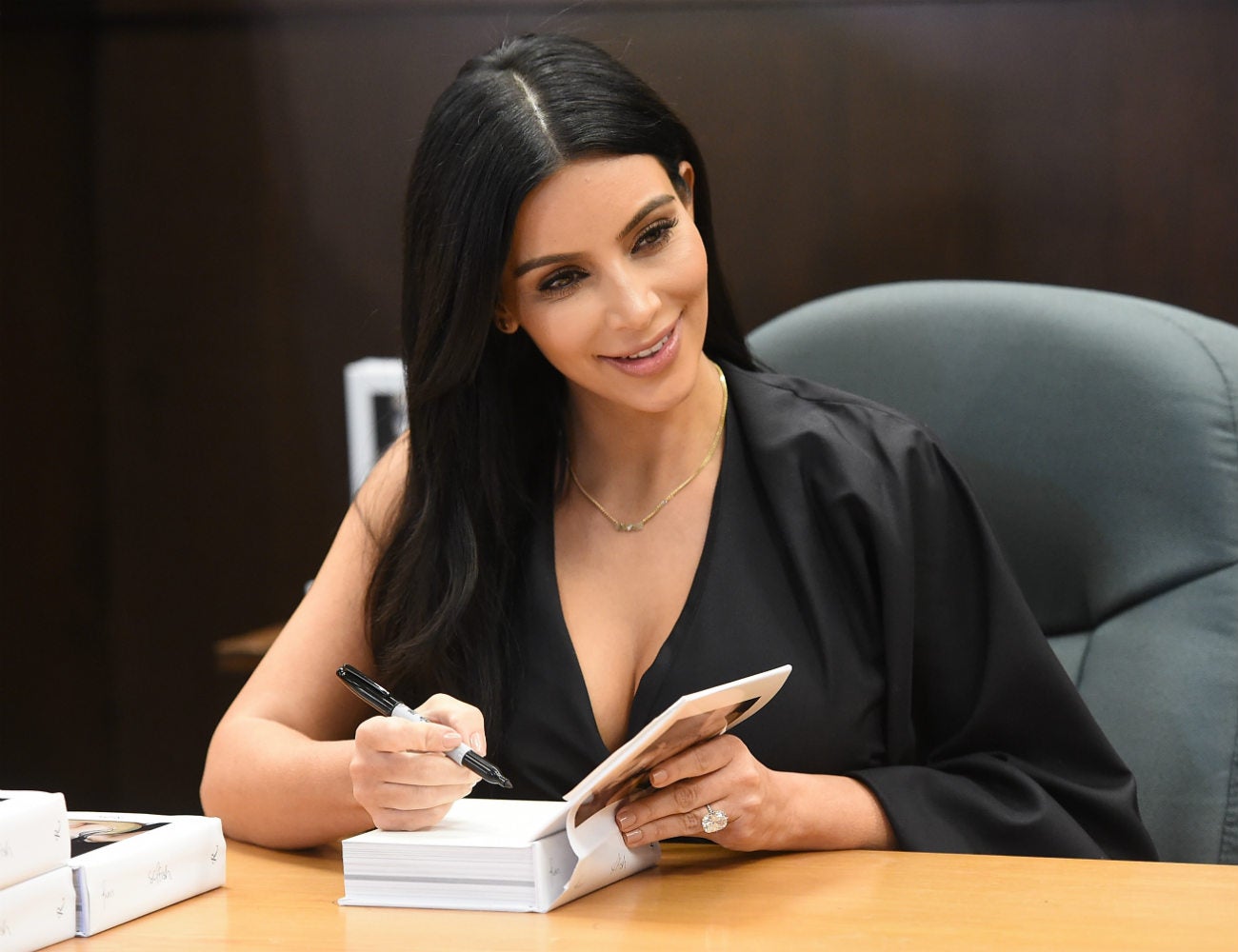

Below are edited excerpts from our conversation. Here's what they had to say about morality in markets; the deceptive tricks of advertisers; that time Shiller ate some of his pet cat Lightning's food to prove a point about marketing. Oh, and Kim Kardashian.

I) On the morality of the free market

Akerlof and Shiller have written an unusual book in that it advocates strongly for morality -- an idea that economists have rarely engaged with.

AKERLOF: The basic idea of this book is that there is a "phishing" equilibrium, in which if there's a profit to be made by taking advantage of your weakness, then that will be there. That's the fundamental idea of the book, and that unites the whole fields of economics and psychology.

The basic idea of psychology is that we're human machines, and as machines we sometimes make errors. What a great deal of psychology does is ferret out what it means for people to make those errors -- how we fail, and why.

In contrast, the basic concept in economics that we use over and over again, is the concept of equilibrium. What we've done is that we've combined these two ideas.

What we say is that if you have one of these fallible desires, as a human machine, even if it's not something that's going to be good for you. The market will take advantage of that just as much as it will provide for the wants that are good for you.

GUO: Embedded in this, I think, is a sense of morality, a sense of fairness. You were saying earlier that this is not something economists really think hard about.

SHILLER: That's considered somebody else's department. That's for the philosophy department. And they don't read anything that philosophers write, most economists.

AKERLOF: Let me continue with this idea of morality, because that is what this book really aims for. The standard view of markets (which is subject to problems of income distribution and externalities) is that markets will deliver the best possible outcome.

GUO: That's a very strong formulation of this idea of market efficiency, right?

AKERLOF: I feel that's what the standard graduate student is taught. It's what you're told to believe, and what I think most economists do believe. As long as the markets are competitive, and there are no problems of income distribution and there are no externalities, it's going to lead to the best possible world. You can't do better.

Now, that then has acquired a moral tone, which is that whatever happens in the market is okay. And that translates, in turn, into people arguing and thinking that it's okay to be selfish. That if I earn this income, then I in some sense deserve it.

So this view that whatever markets do is good becomes this idea that whatever markets do is right.

II) On the origins of laissez-faire

"Laissez faire" is a conservative mantra now, but back when it was introduced, it was a progressive idea. We talked about how, as a society, we forget that economists have never been absolute advocates for the free market.

GUO: There's this really great interview out there with economist Alan Kirman in which he talks about the history of this laissez faire idea. There are a lot of misconceptions about Adam Smith, about how much Smith actually believed in totally free markets.

SHILLER: He wasn't so one-sided.

GUO: He wasn't so one-sided! And here's Kirman tracing the origins of this idea back to the Enlightenment. He says, "laissez faire made a lot of sense against the background of monarchy and controlling church." So this idea of freeing the markets really came through at a time when businesses were being particularly oppressed.

AKERLOF: Yes, that's right. Adam Smith was very progressive for his time. He was arguing that businesses and the bourgeoisie, they were okay. This was at a time when the nobility were dominant. Back then, the view that business was good was in fact very progressive.

Now, several centuries have elapsed, and now we're getting to the view that business is the only thing, and we shouldn't have other values. So instead of this being a progressive value, this actually has become a value that basically says that greed is healthy.

I feel a lot of our politics enshrines this view, that whatever the market does is in fact good and we shouldn't interfere with it. But markets not only have a huge upside, they also have huge downsides. That's what we look at in the book, the downsides.

SHILLER: Can I add something to that?

It's also that there are many alternative worlds that could exist that differ in lot of details. The one that we live in is the one that optimises “wantability.” It’s not what optimises utility.

Irving Fisher was a Yale economist who in 1918 wrote a book saying the free market system is maximizing something but it’s not what Jeremy Bentham, the philosopher, called utility. So he named it wantability.

I did a Google N-grams search [how often a word appears in books] for wantability. The term enjoyed some popularity in the 1920s and 1930s, then exponentially decayed. After the Reagan-Thatcher revolution the term was gone.

III) On how markets manipulate us

A key point in Akerlof and Shiller's book is that we are all subject to desires that will benefit us, as well as desires that will harm us. Advertising often targets our inner demons, not our rational better selves.

GUO: I think that really gets at an important distinction that the book tries to make. It's a distinction that many people may find uncomfortable. This space between "utility" and "wantability" -- how narrow is it? What is the difference, and who is to say what that difference is?

SHILLER: Well the problem is the answers are being given by wonks -- the food engineering, the gambling engineering. It goes down to little details that you think are random. They're not random.

Earlier we were talking about the candy bars at the checkout counter at the grocery store, and how thirty years ago there was an attempt to stop doing that. But that's all forgotten. The economic forces win out eventually.

Not only that, but George was saying he also noticed that the children's candy bars were put at children's eye level

AKERLOF: -- in the Safeway on Wisconsin Avenue.

SHILLER: It's the little things you wouldn't even think of. You have professionals who are designing everything. They are designing it for wantability.

IV) On eating cat food

Shiller has become somewhat notorious for eating gourmet cat food because he wanted to prove that, well, it's not gourmet -- not even close.

GUO: You mention this anecdote about eating "fancy" cat food and finding out that it all tastes the same. This is example of how these stories that advertisers tell are not in our best interest -- or in the best interest of our pets, in this case. The fancy labeling is an example of deception.

SHILLER: They have deniability. You can't show they were fraudulent. If they name a cat food "beef stroganoff" flavored, and I taste it and say it doesn't taste anything like beef stroganoff, and it tastes horrible, well there's deniability. They can say, well your cat eats it right, so what's the problem?

The problem is it's all phony, the labels!

GUO: You have a cat?

SHILLER: Yes, well I had a cat and I tasted its food.

GUO: What kind of cat was it?

SHILLER: It was multi-colored, sort of a mutt-type cat.

GUO: A boy or a girl?

SHILLER: It was a girl.

GUO: What was its name?

SHILLER: Lightning.

GUO: So at some point in the course of writing this book you tasted --

SHILLER: Now it must be that most people don't. Otherwise manufacturers wouldn't use this advertising.

GUO: I just can't imagine that you actually did it.

SHILLER: Well I didn't eat the whole can!

GUO: Well how much did you eat?

SHILLER: Just enough to taste it. Why is there such an aversion to cat food?

AKERLOF: Doesn't it smell really bad?

SHILLER: I've had food in restaurants that I liked less. (Turns to Akerlof) Like today, I didn't like that salad... (Laughs)

AKERLOF: We won't tell you where we ate!

GUO: You know they have treats now for humans and pets.

AKERLOF: Really!

SHILLER: How about Oreos? Dogs will eat Oreos.

GUO: I'm...not sure about that. But anyway -- this is about the power of stories, right? But stories aren't just ways to manipulate us. Stories are ways that we create happiness.

AKERLOF: Sure, yes!

SHILLER: We have a paternal or maternal instinct. We don't always have children around, so that instinct is exploited by sellers of pets. A lot of people pride themselves on how they indulge their pets. They seem to respond to a story that this is just sick indulgence. You are just so good to your pet.

GUO: And you don't think this creates value? Really, who is being harmed? You feel better about yourself, that's utility. The extra 25 cents they charge, maybe they're charging you because the food actually tastes like beef stroganoff -- they're charging you for the story.

AKERLOF: Again, the initial title of this book was Common Sense. If this gives people utility and it causes no harm, then that's fine. But if it causes people to get cancer because they smoke too many cigarettes, or the kids are going to get diabetes, or financial markets crash, or if the political system isn't working -- we don't want that.

But if Bob feeds the cat the fancy cat food, and he feels good about it, then okay let him. I'm not going to worry about that.

IV) On the morality of gambling

Akerlof and Shiller point to the gambling industry as an example of a business that can profit off of people's addictions. Are casinos taking advantage of people, or just giving the public what it wants?

GUO: If you look at the steady stream of results coming out of behavioral economics, the steady stream of examples of people doing irrational things, at some point -- and I think this is the point that this book is trying to make -- you have to believe that this is not the exception anymore. This is the rule.

AKERLOF: Exactly. This is exactly what the whole point of the book is about. This generalizes the whole idea of behavioral economics. What behavioral economics is mainly about is showing that people have weaknesses.

We're taking this and we're making a much much bigger point. We're saying if you have a weakness, then the system is going to come in and get you, as long as there's a profit to be made. What our book does is show first of all that the manipulation is going to be there, it's going to be pervasive.

GUO: Let's look at gambling as an example. We can look at the history of gambling, at the ways in which we have recognized for millennia that this is a flaw in the way that we operate. There are people who are very prone to addictive behavior who can be taken for all they're worth.

The question is what is the solution to this problem? In the past there were lots of moral forces that tried to constrain this, but --

AKERLOF: It wasn't just moral forces. There were legal forces. There were restrictions on gambling.

I think that the new view, which says whatever markets do is right, has legitimized the idea that people should be able to gamble, even if that leads to lots of addiction, and lots of ruined lives.

And maybe life might be better if we went back to the gambling customs of the 1940s or '50s. In this respect we might save a significant fraction of our population from something that is really hell.

SHILLER: Instead we're going in the other direction, with improved machine gambling that is much more addictive and more calculated to addict you.

GUO: I think the objection is that most people think they're not going to fall for this. It's someone else's problem. There's a sense that gambling is a personal problem. It's not a systemic problem. It's not a market failure.

AKERLOF: That's the heart of this book. These things that you could classify as a personal failure are conditions that lead to very serious problems and play a major role in making our lives rich than they could be.

SHILLER: It leaves to divorces and family conflicts --

AKERLOF: -- and a great deal of unhappiness. Why should we have that?

And the amazing thing about gambling is that not only do we allow it by the private sector, states engage in state lotteries, which take in huge amounts of money.

GUO: Well, why shouldn't we have lotteries in lieu of taxes? The argument is that people who play the lottery are voluntarily giving up their money, and that society as a whole benefits.

AKERLOF: Not everyone, because they lose.

SHILLER: They don't understand the numbers. They're doing it because of either an addiction, or a faulty understanding of the probability of winning. So we're duping them and taxing them heavily -- low income people generally -- and I don't think that's a good thing to do. You have people who keep going back every day buying a ticket.

I can't think this is a public-spirited thing to do. You know that they're either confused or addicted.

GUO: Isn't that a very paternalistic thing to say?

SHILLER: Is redistribution, is a progressive tax system a paternalistic thing?

AKERLOF: You suggested earlier in the interview it was reasonable to have taxes on tobacco -- we think that is a very good thing. The same principle applies. You just have to think that being addicted to gambling is comparable to being addicted to tobacco.

V) On why Kim Kardashian is always in the news

We talked for a while about why so much junk news and clickbait is published. This is an example, Akerlof and Shiller argue, of the curse of markets giving us exactly what we want.

GUO: Do you have a favorite anecdote from the book?

SHILLER: The Malaysian Airlines story. This is the first one we're talking about -- the one that took off for Kuala Lumpur for Beijing [and then disappeared].

The question is why was that so much in the news? How did that get amplified? Of course, a couple hundred people lost their lives, but this is a world of seven billion people. There are people losing their lives all the time. Is this the best use of our time? Why is this such a big story?

I don't mean to be accusing, but why did this stay in the news?

Newspaper people have an instinct for what kind of story will keep people coming back. The Malaysian Airlines story has a mystery quality to it, and we just enjoy mystery stories. You can come up with your own theory. I had my own theory. I was remarking to George that I thought about it about it many times, about what really happened.

I have another example: The theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre. Can you believe this: Some guy broke into the Louvre at night and stole the Mona Lisa. He was at large for four years, and the police kept trying to find him. You, as a newspaper person, have to know that it was a great story.

Did you know that the Mona Lisa was not very famous until that? It was sort of famous. It was known as an important painting. But the talk about the Mona Lisa was ten times greater after that. Now, the Mona Lisa is just a hugely important brand. The truth is, it's not such a great painting. It's a good painting -- I'm not criticizing it. But why does it stand out in our imagination? It's because the news media had a good sense to know a good story when they saw it.

People don't know the media has this power. Well, it's not exactly a power. It's recognizing a good story and running it, and forgetting all the important stories.

GUO: It's trying to give people what they want. Not necessarily what they say they want, but what they really --

SHILLER: -- but what they really want, yes. If you sat down with them and asked them do you really want us to hype stories about Kim Kardashian all day? And they might say no, in their better moments.

GUO: And people make fun of outlets that run these Kim Kardashian stories, but at the end of the day, we would stop running those stories if people would stop clicking on them.

SHILLER: This book is not just about policy. It's about quality of life. You thought that the Mona Lisa was talked about because it's such a wonderful painting. People don't realize that you have opportunists in the media looking all the time looking for stories that they can sell.

I don't think people realize to what extent it affects what we pay attention to, what we're thinking about. Part of this point of this book was just to document how these things happen, because you might otherwise think that all the things we talk about are the most important things. That's not true.

GUO: But there's a moral judgment implicit in that. We're talking about a time inconsistency in people's preferences. If you solicit their opinions about what they want to read or watch, it's different than what they actually read or watch in the moment. So the question is --

SHILLER: So the question is which is right.

GUO: Yes! Netflix is another example here. Back when everybody got the DVDs in the mail, people would queue up documentaries about Rwanda -- but when it came time to actually watch these movies, they moved the romantic comedies to the top of list because that's what they really wanted to watch.

AKERLOF: We don't need to solve this question on every issue. But you can see if the balance is very highly weighted in one way or the other. That's why what we say about the book is that we have this theory, but then the onus is on us. The onus on us to show that indisputably, people are making decisions that they themselves would consider dysfunctional if they were thinking hard about it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments